8

Art in the Alphabet.

#Ш0СШР(ЖАТОУѲеОУАОІОІС

.ошсШошевпоіѳожіфш-

;ттАсшгихоісшшѳемеыгетштАфш-

ШС}ШШІгІАНпГ#НІШРПІОІІС-

ШШштЖашатщшЁ

Шфтйттешктш

шшшштШтшЩщ

ѲШХААІНШШШІПШКЕІЕ)

шсіад#Астюшютанш.

рішошеяшшршанеквш-

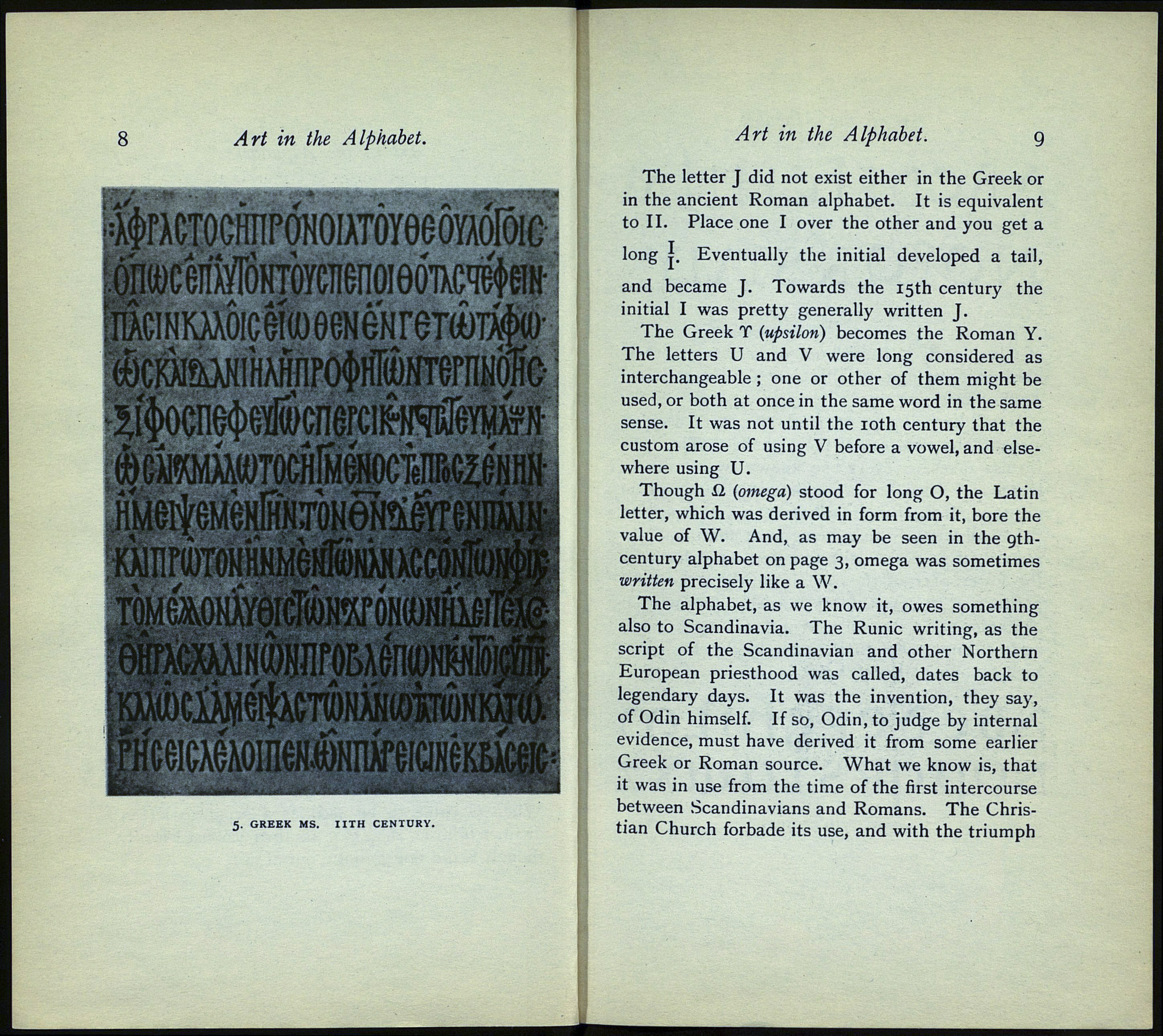

5- GREEK MS. ІІТН CENTURY.

Art in the Alphabet. g

The letter J did not exist either in the Greek or

in the ancient Roman alphabet. It is equivalent

to II. Place one I over the other and you get a

long j. Eventually the initial developed a tail,

and became J. Towards the 15th century the

initial I was pretty generally written J.

The Greek T {upsilon) becomes the Roman Y.

The letters U and V were long considered as

interchangeable ; one or other of them might be

used, or both at once in the same word in the same

sense. It was not until the 10th century that the

custom arose of using V before a vowel, and else¬

where using U.

Though Í2 {omega) stood for long O, the Latin

letter, which was derived in form from it, bore the

value of W. And, as may be seen in the 9th-

century alphabet on page 3, omega was sometimes

written precisely like a W.

The alphabet, as we know it, owes something

also to Scandinavia. The Runic writing, as the

script of the Scandinavian and other Northern

European priesthood was called, dates back to

legendary days. It was the invention, they say,

of Odin himself. If so, Odin, to judge by internal

evidence, must have derived it from some earlier

Greek or Roman source. What we know is, that

it was in use from the time of the first intercourse

between Scandinavians and Romans. The Chris¬

tian Church forbade its use, and with the triumph