A System of Classification

Most text typefaces can be classified into

one of two groups: those with serifs and

those without. Over the years, in order to

further categorize typeface design traits,

several more definitive systems were devel¬

oped, some with over a hundred different

categories. While two broad categories of

type are inadequate for understanding the

full extent of typographical development

and diversity, hundreds can be self-defeat¬

ing. In what is hoped to be a reasonable

compromise between the two extremes,

the system of classification that follows uti¬

lizes nine basic groups, some of which have

been subdivided further for added clarity.

While there may be some differences

between this and other type classification

systems, as well as disagreements concern¬

ing the placement of a typeface or two, the

intent here is to provide a set of working

guidelines for the typographic communi¬

cator—with an emphasis on the word

“guideline.” The good news is that few

things typographical can be rigidly defined,

fostering the potential for healthy debate

and leaving those who relish the finer

points of type unimpeded by an inflexible

system of standardized models.

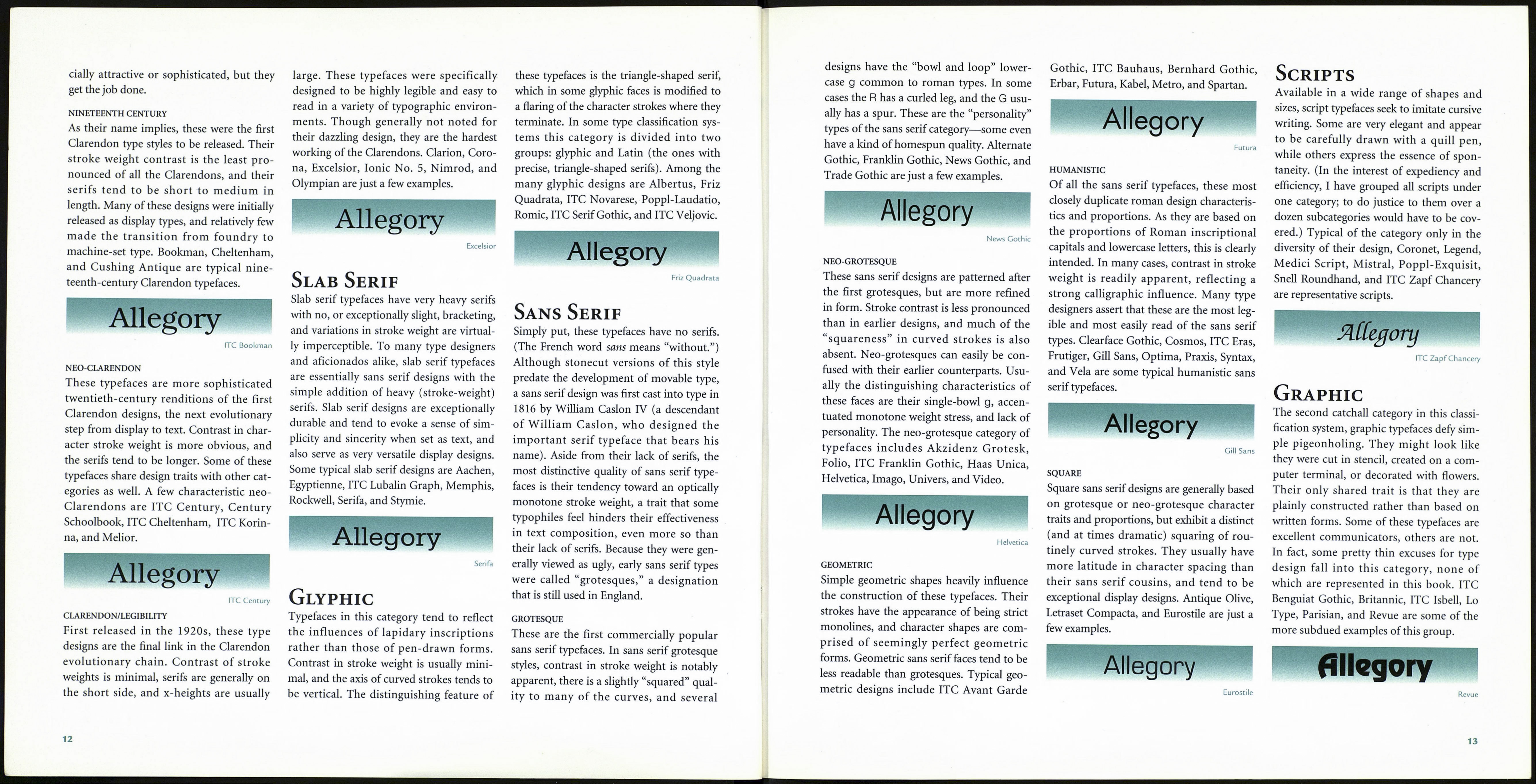

Old Style

The first roman types, old style faces were

created between the late fifteenth and mid¬

eighteenth centuries, or are patterned after

typefaces that were designed during that

period. In these designs, the axis of curved

strokes is normally inclined to the left, so

that the weight stress falls at approximately

eight and two o’clock. The contrast in

character stroke weights is not dramatic,

and hairlines tend to be on the heavy side.

Some versions, like the earlier Venetian old

style designs, are distinguished by the diag¬

onal cross stroke of the lowercase e. Serifs

are almost always bracketed in old style

designs, and head serifs are often angled.

VENETIAN

These are the first of the old style faces,

created in Venice around 1470. They gen¬

erally take their style and proportions from

handwritten letters drawn with an oblique¬

ly held broad-nibbed pen. A dead giveaway

for Venetian old style designs is the diago¬

nal cross stroke of the lowercase e; almost

every example has one. Venetian old style

faces also have very minor contrast in

stroke thickness and their serifs are heavily

bracketed. Some typical designs are Bauer

Text, Centaur, Cloister, Cloister Old Style,

Deepdene, Kennerly, and Italian Old Style.

Allegory

Deepdene

ALDINE

Aldine old style designs are based on the

original work of Aldus Manutius during

the early 1490s. During the sixteenth cen¬

tury these models were adopted and emu¬

lated first in France, then throughout

Europe. (It is probably one of the first

typefaces to have undergone widespread

duplication—sort of the Helvetica of its

day.) These typefaces generally have more

contrast in stroke weight than Venetian

old style designs, and the crossbar of the

lowercase e is almost always horizontal.

Serif bracketing is also obvious, but usually

not as pronounced as in earlier designs.

Among Aldine old style designs are

Bembo, Garamond, Goudy Old Style,

Palatino, Sabon, and Weiss Roman.

Allegory

Bembo

DUTCH

In the Netherlands, the larger x-height,

darker color, and enhanced contrast in

stroke weight of the German blackletter

were melded with Aldine design traits,

resulting in Dutch old style designs. This

style first appeared in the mid-sixteenth

century, but continued to be developed and

refined well into the twentieth. These are

heavy types that tend to be exceptionally

legible and readable. Caslon, Concorde,

Janson, and Plantin are just a few examples.

Allegory

Janson

REVIVAL

There are two catchall categories in this sys¬

tem, one of which is the revival group of

typefaces. These may display a predomi¬

nance of old style design traits, but are gen¬

erally not patterned after any particular

type of the period. Many times, in fact, they

share several design influences. As with

other old style designs, however, character

stroke width and contrast are relatively

conservative, weight stress is inclined, and

serifs are bracketed. The revival category

includes designs such as ITC Benguiat,

Cooper Black, ITC Galliard, ITC Gara¬

mond, Italia, Raleigh, ITC Tiffany, Trump

Mediaeval, ITC Weidemann, and Windsor.

Allegory

Cooper Black

Transitional

The style for these typefaces was established

in the mid-eighteenth century, primarily by

the English printer and typographer John

Baskerville. His advancements in paper-

making and printing allowed much finer

character strokes to be reproduced and

subtler character shapes to be maintained.

While the axes of curved strokes are usually

inclined, they generally have a vertical

stress. Weight contrast is more pronounced

than in old style designs, though the serifs

are still bracketed and the head serifs

oblique. These typefaces represent the tran¬

sition between old style and modern

designs, incorporating characteristics from

both categories. Included in this group are

Baskerville, Caledonia, Fairfield, Perpetua,

ITC Usherwood, and ITC Zapf Interna¬

tional, as well as many others.

Allegory

Baskerville

Modern

The work of Giambattista Bodoni in the

eighteenth century epitomizes this style of

type. Modern type designs, when they were

first released, were referred to as “classical.”

Early on, however, it became apparent that

these were not updated versions of classic

type styles, but altogether new ones. As a

result their designation was changed to

“modern”—which they in fact were at the

time. Here, contrast between thick and thin

strokes is abrupt and dramatic, and the

axes of curved strokes is vertical with little

or no bracketing. These tend to be highly

mannered designs that are obviously con¬

structed, rather than drawn. Moderns are

plagued by the dreaded typographic disease

of “dazzling,” in which the strong vertical

stress creates a “picket fence” appearance

that tends to vibrate on the page. These are

the aristocrats of type: beautiful to look at,

though somewhat unapproachable.

DIDONE

Setting the standard for all other modern

type designs, Didone typefaces were creat¬

ed during the eighteenth century, or are

directly descended from those designs.

Didones normally have slightly heavier

hairline strokes than twentieth-century

moderns. Some have slight, almost imper¬

ceptible serif bracketing; however, most do

not, and the serifs themselves are generally

not much more than simple hairlines

tacked on to the ends of vertical strokes. In

many cases, stroke terminals end in a ball

shape rather than the type of end stroke

created by a broad-nibbed pen. Typical

Didone designs include Bauer Bodoni,

Bodoni, Didot, and Torino.

Allegory

Bauer Bodoni

TWENTIETH CENTURY

These typefaces were created during the

twentieth century, and while they may

share many design traits with Didones,

they were generally not intended as

revivals of those earlier designs. Twentieth-

century moderns also tend to be more styl¬

ized than their predecessors. ITC Fenice,

Franklin Antiqua, Linotype Modern, ITC

Modern No. 216, Berthold Walbaum Book,

and ITC Zapf Book are among the many

twentieth-century modern type designs.

Allegory

ITC Fenice

Clarendon

This style of type first became popular in

the 1850s. Like the Didones before them,

Clarendons have a strong vertical weight

stress, but this is their only similarity. While

Clarendon designs have obvious contrasts

in stroke thickness, they are not nearly as

dramatic as in the Didones. In addition, ser¬

ifs in Clarendon designs are normally heavy,

bracketed, and usually square-cut. These are

the typographic workhorses: robust designs

that can tackle virtually any task with pre¬

dictably successful results. They aren’t espe-

11