Punctuation

Lord Timothy Dexter wasn’t really an aris¬

tocrat, but he was a shrewd businessman.

He made a fortune by reclaiming at full

value depreciated Continental currency

that he had acquired during the Revolu¬

tionary War. As is evidenced by his inordi¬

nate affection for patrician titles, he was

more than a little eccentric.

Dexter was also a writer of sorts. His

best-known book is A Pickle for the Know¬

ing Ones, which is remarkable only for its

complete lack of punctuation. To its sec¬

ond edition Dexter added a page filled with

periods, commas, semicolons, and other

punctuation marks, so that readers could

“pepper and salt it as they please.” While it

may seem that Dexter’s disregard for prop¬

er punctuation was just another of his

idiosyncrasies, it is absolutely in keeping

with the heritage of our written language.

The earliest hieroglyphic and alphabetic

inscriptions had no such symbols—no

commas to indicate pauses, no periods

between sentences—in fact, there weren’t

even spaces between words. Even the early

Greek and Roman writers didn’t use any

form of punctuation. In later formal in¬

scriptions, word divisions were indicated

by a dot centered between words. Still later

(probably out of expediency), spaces began

to replace the dots. Gradually spaces be¬

tween words became more popular, and by

A.D. 600 the convention was quite com¬

mon. In some early medieval manuscripts,

the punctuation mark representing a full

stop at the end of a sentence—two vertical¬

ly aligned dots—looked just like our colon.

Subsequently one of the dots was dropped,

and the remaining dot served as a period,

colon, or comma, depending on whether it

was aligned with the top, middle, or base

of the lowercase letters.

When the English scholar Alcuin estab¬

lished a consistent writing style for all

scribes in the Holy Roman Empire in the

ninth century a.D., the principal result was

the Caroline minuscules, the forerunners

of our own lowercase letters. Another

important consequence of Alcuin’s system¬

atic approach to graphic communication

was the first attempt at standardizing the

marks and use of punctuation. Aldus

Manutius, the Renaissance typographer

and printer who was one of the first pub¬

lishers to revive the works of classical

Greek philosophers and who oversaw the

design of the first italic letters, more firmly

established Alcuin’s reforms through con¬

sistent usage. Manutius used a period to

indicate a full stop at the end of a sentence,

and a diagonal slash to represent a pause.

The basic form of the question mark,

which was once referred to as the “inter¬

rogative point,” was developed much later,

in sixteenth-century England. Most typo¬

graphic historians contend that the design

for the question mark was derived from an

abbreviation of the Latin word quaestio,

which simply means “what.” At first this

symbol consisted of a capital Q atop a low¬

ercase o. Over time this early logotype was

simplified to the mark we use today.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth cen¬

turies, quotation marks, the apostrophe,

the dash, and the exclamation point be¬

came part of the basic set of generally

accepted and consistently used punctuation

marks. The initial configuration of the

exclamation point (referred to as a “bang”

or a “screamer” by old-time printers),

which is also descended from a logotype for

a Latin word, io (“joy”), was a capital I set

over a lowercase o. Gradually, as with the

question mark, the design of the exclama¬

tion point was reduced to its present form.

Our repertoire of punctuation contin¬

ues to expand today. As recently as the

1960s, a new mark, the interrobang, a liga¬

ture of the exclamation point and question

mark, was suggested to punctuate sen¬

tences like, “You did what?!”

Punctuation

Design

The type designer must keep in mind that

punctuation marks are an integral part of a

typeface design. They should not be treated

as separate pi characters or as standard

forms that can be thoughtlessly combined

with each and every type design. For in¬

stance, the question mark in ITC Anna

simply wouldn’t work with typefaces like

ITC Highlander or ITC New Baskerville,

and even the humble period from ITC

Tiepolo would look completely out of

place with a design like ITC Franklin

Gothic or ITC Fenice.

116

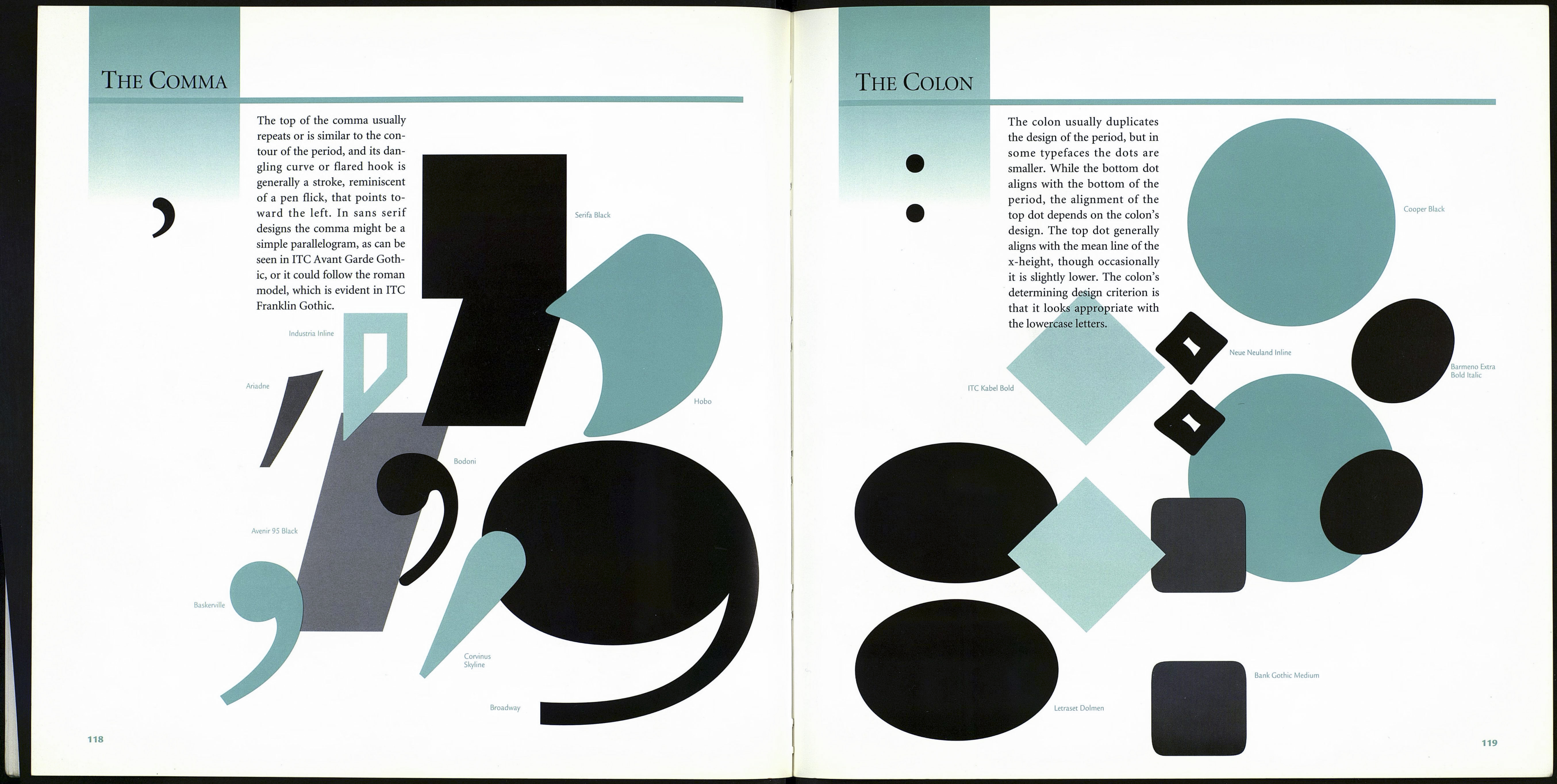

The Period

Letraset Citation

Letraset La Bamba

Goudy Old Style

Bovine Poster

Letraset

Follies

In a roman design, periods are

usually rounded forms, while

in sans serif faces they can be

round, square, or rectangular,

depending on the design and

proportions of the typeface. In

alphabets that reflect a calli¬

graphic influence, periods are

often diamond-shaped.

The weight of the period is a

critical design decision for two

reasons: first, because it estab¬

lishes the weight for many of the

other punctuation marks; sec¬

ond, because it must be heavy

enough to be easily noticed, but

not so massive that it is con¬

spicuous within a page of text.

Arcadia

osmos Extra Bold

ITC Mona Lisa Recut

Helvetica Black

Ironwood