HALF-UNCIALS

Early in the sixth century, a writing style

now known as the half-uncial came into

general use. Despite its name, this style did

not evolve from the uncial, but developed at

the same time, out of the need for an easier,

more condensed, and more readable writ¬

ing style for secular documents. The half¬

uncials embodied further advances toward

our lowercase letters, as the scribes took

more and more liberties with the capital let-

terforms. In fact, the half-uncials are often

categorized as small letters, and some claim

that they represent the invention of the first

lowercase alphabet. Except for the letters J,

U, and W, the basic Latin alphabet was

established by that time. But the widespread

adoption of small letters in a uniform way

was quite another matter. In fact, matters

got worse before they got better. What uni¬

formity in lettering there was began to dis¬

appear in the fifth century, following the

disintegration of the Roman Empire.

deinrsc

Half-Uncials

National Hands

As Christian missionaries spread out over

Europe from Rome, they carried with them

Bibles and other religious writings. The

missionaries soon had local monks at work

producing new copies in the monasteries

they established. The uncials and half¬

uncials generally served as the basis for the

letters used to copy the manuscripts, but

the monks were influenced by local tastes,

customs, art, and styles of decoration. Out

of this mixture came what we today call the

various “national hands.” These styles of

writing were particular to each geographic

location, and although they are referred to

as “national,” many times writing styles

varied within just a few miles of each other.

The most beautiful of the national

hands was the Irish. Because Ireland had

never been occupied by the Romans, its

predominant writing style exhibited no

direct influence of the Roman hands. St.

Patrick is credited with introducing this

writing style to the tiny island country. The

Irish hand in turn influenced the Anglo-

Saxon national hand, when Irish mission¬

aries traveled into Scotland in about A.D.

650. One of the most beautiful works of

calligraphic art, The Book of Kells, was pro¬

duced in the Irish hand in about a.d. 800.

oe-TTiRSC

Irish National Hand

A Point of

Demarcation

When Charlemagne ascended the throne of

the Holy Roman Empire in the late eighth

century, he expanded reforms begun earlier

by his father, Pepin, and intended to imple¬

ment sweeping changes in learning and

civic life. During a visit to Parma, Charle¬

magne met Alcuin, a well-known English

scholar. Impressed with Alcuin’s scholar¬

ship, Charlemagne invited him to organize

the educational system of his domain.

Alcuin accepted the challenge and began

his task by standardizing a copying style for

the many new versions of the Vulgate Bible

that were required. One of the results of the

search for a clear copying style was the Car¬

oline minuscule, the forerunner of our own

modern lowercase letters.

Caroline Minuscules

In general, the Caroline minuscules

eliminated cursive forms and avoided liga¬

tures, making letters independent of one

another. When ligatures were used, they

resulted in only slight changes in form.

Also, these letters were drawn more full-

bodied than their predecessors. All these

characteristics adapted themselves easily to

the invention of movable type by Johann

Gutenberg in the mid-fourteenth century.

The Design of the

Lowercase Letters

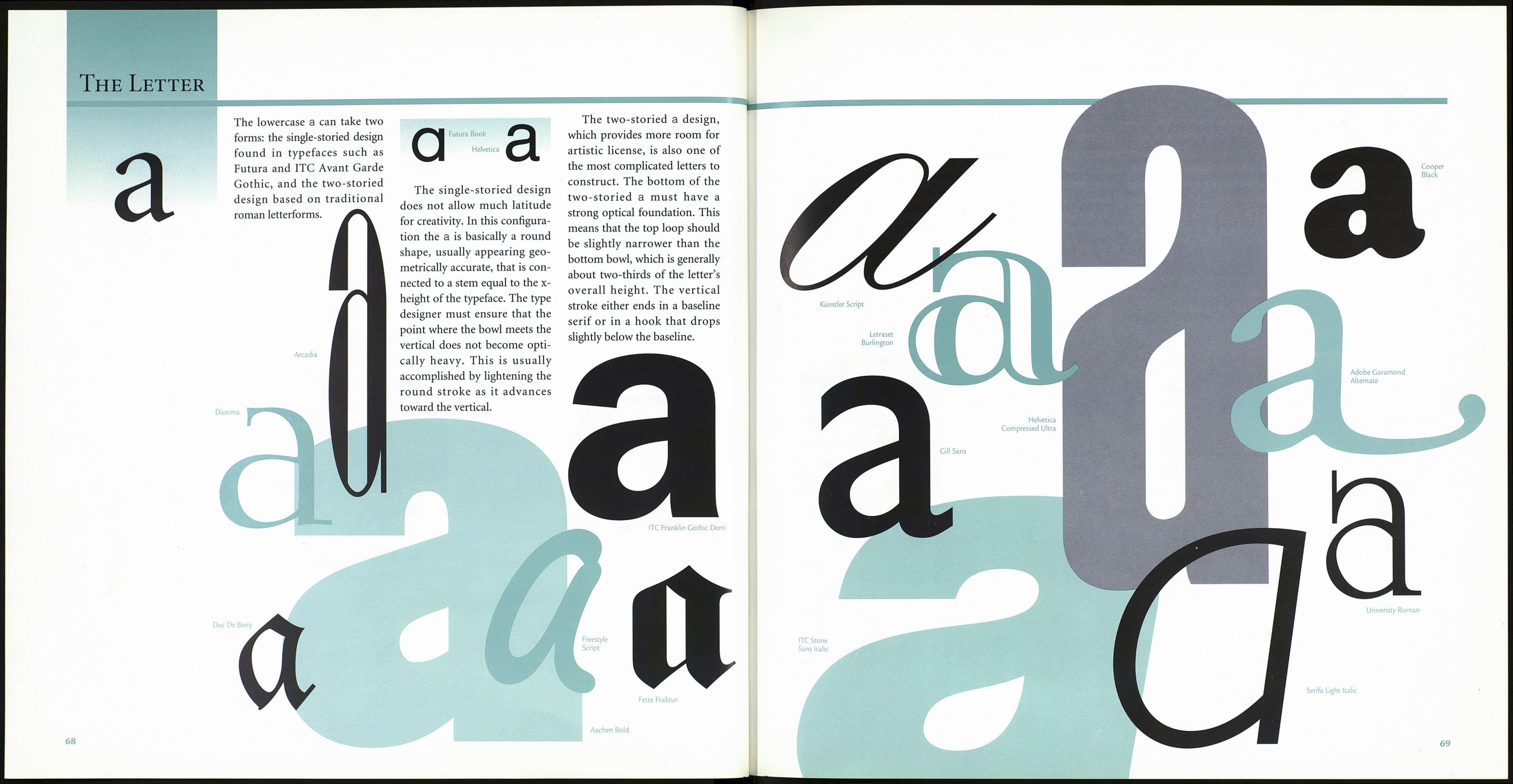

One of the first decisions a type designer

makes when designing a lowercase alpha¬

bet is its x-height: How tall should letters

like а, с, i, m, n, o, and x be in relation to

66

the capitals? Some typefaces, like Nicholas

Cochin, have very small x-heights, while

others, such as Americana and Antique

Olive, have x-heights whose proportions

border on the heroic. Old style designs

tend to have relatively small x-heights,

while those of more recent designs are gen¬

erally larger. During the 1960s and ’70s it

was popular to design typefaces with

exceptionally large x-heights. The theory

was that since lowercase letters were the

most important for text composition, the

bigger they were, the more readable the

typeface would be. The premise of the

argument is sound—over 90 percent of

text composition is set in lowercase letters

—but the inference is not necessarily true.

If the lowercase alphabet’s x-height

becomes too large, readability can actually

be impaired. A general guideline for com¬

puting a sensible x-height is that it should

be between 56 and 72 percent of the height

of its capital letters.

Next, the designer establishes the height

of the ascenders and the length of the

descenders. These measurements can be

the same, though sometimes ascenders are

longer than descenders. In some alphabets

the ascenders are the same height as the

capitals, but in many instances they are

slightly taller.

Finally, the designer determines the

weight of the characters—one of the most

important decisions he or she makes. If

over 90 percent of the letters we read are

lowercase, then their weight and how they

“color” a page are critical to the overall

design of a typeface.

Square Capital

Roman Cursive

Half-Uncial

Uncial

Caroline Minuscule

67