Adventure and Art

Art Library

Illustration

The ten illustrations exhibited here demonstrate a vari¬

ety of illustrative approaches and engraving methods

favored by the first artists and artisans of the printed book.

It is difficult to generalize too broadly about illustration

during the period under consideration, as it was an era of

rapid innovation and varied production. One can however

note that scholarly study of the earliest illustrated books

focuses on several interrelated characteristics. Early wood¬

cuts tend to be simple in design, meant to achieve maxi¬

mum legibility and swift "readability" of the image; the

image sometimes symbolizes, rather than iterates or hypos-

tatizes, a specific textual element. Contrary to modern

practices, a woodcut might be printed multiple times

within a text and represent two or more different cities

or personages (as in Schedel's Liber chronicarum—#A1),

different saints or martyrs (as in the Legenda Aurea-#31),

or different scenes in an imaginary narrative (as in Dante's

La Commedia—# 18). While a modern audience might find

this nonrepresentational approach to illustration inadequate

or disconcerting, Renaissance readers understood that

illustrations gestured toward realities underlying the par¬

ticulars of the text, and lent historically separate events a

degree of relationship, constructive coherence, and intelli¬

gibility. Perhaps they also accepted that the expense and

beauty of a woodcut justified its redundancy.

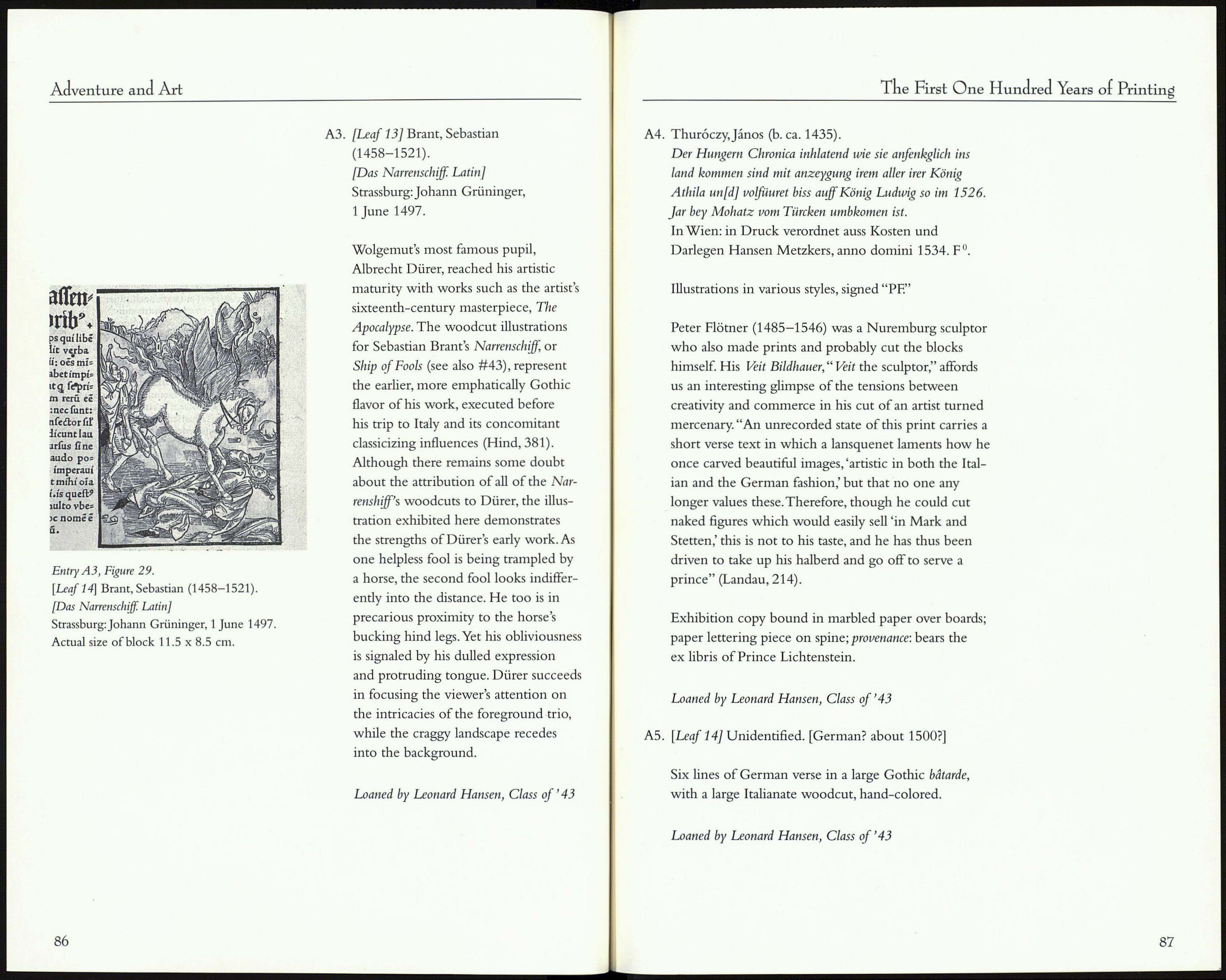

Al. [Leaf 11] Schedel, Hartmann (1440-1514).

[Liber chronicarum]. Liber cronicarum.

Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493.

German book illustration profited from a highly

organized relationship between publisher and artist.

Hartmann Schedel's liber chronicarum, or Weltchronik,

serves as a prime example. Painter Michel Wolgemut

and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff cut 645 wood blocks to

form a suite of over 1,800 illustrations in the final

84

The First One Hundred Years of Printing

text. Many views of town and cityscapes are included,

though Arthur Hind notes that there exists "only a

beginning of a faithful topography in the views"

(Hind, 375). Certainly, faithfulness could not decently

be claimed when a woodcut illustrating Maguncia

(i.e., Mainz, the birthplace of printing), also must

illustrate Lyon, Bologna, Naples, and several other

European cities as well. As Dale Roylance notes, such

duplication remained acceptable in a period hovering

between the late Gothic and early Renaissance due to

"a lingering medieval regard for symbol over reality"

[i.e., material actuality] (Roylance, 14). (See also #4.)

A2. [Leaf 12] Bible. German. 1483.

[Nuremburg: Anton Koberger, 1483]

Hand-colored woodcut illustration from the Book

of Exodus (see #30).

The effective simplicity of early German book illustra¬

tion is evidenced in a leaf from the German Bible

(Bible. German. 1483) of Anton Koberger. In a scene

from Exodus (7: 8-10), Moses and Aaron are sent by

God to deliver the Israelites from Egypt. As Aaron

throws down his staff in front of the pharaoh, it imme¬

diately becomes a serpent. In the accompanying illus¬

tration, the primary characters, Pharaoh, Aaron, and

Moses, are positioned frieze-like across the picture

plane, and are identified by label. Despite the elaborate

architectural backdrop, the scene is minimally land¬

scaped, drawing attention to the human participants

and the radically transforming staff. "Vivid hand-

ground colors so characteristic of the fifteenth cen¬

tury" serve to set the woodcut starkly apart from the

surrounding text (Roylance, 12).

85