The €ЛѴо.

U their indchleánt

LiNcrrvfE £i ЫдоЮПЯУ Limited of London

Ml. GsutcE W. Jones o/ tcWon

una/ particularly lo

"Two L'EUTUIIIES OK Tvi-EFOUNDINC"

Л ff("(l«rT o/ íAf С<"'ои Foundry

'Prìntti bj Çfor£r \V. Jone, et Thr Sign of the 'Dolphin

London, ICIO

from which hai km attained much of ihr material

uifA in the following fagei

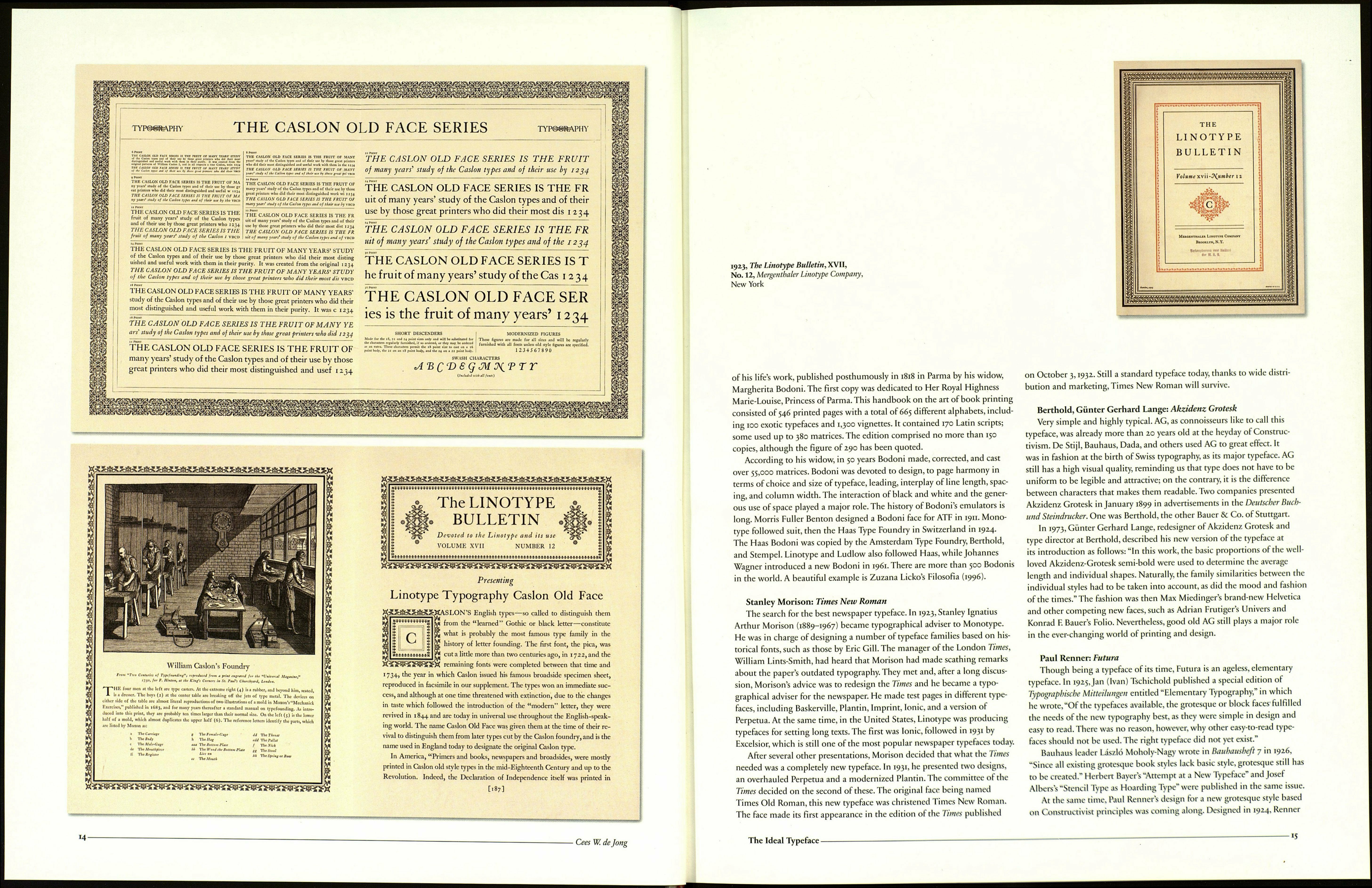

1923, The Linotype Bulletin, XVII,

No. 12, Mergenthaler Linotype Company,

New York

The Linotype Bulletin, a publication for

the clients of this type foundry.

Eine Ausgabe des Bulletins, mit dem

sich die Schriftgießerei Linotype ihren

Kunden präsentierte.

The Linotype Bulletin, une publication

destinée aux clients de cette fonderie

de caractères.

Josef Albers's "Stencil Type as Hoarding Type" were published in the same

volume.

Before the start of World War II, the progressive forces in typography

were resisted, overcome, and suppressed—just like what was happening

in the political arena. Many typographers had to change their style or emi¬

grate. In Germany, archaic design rules were reintroduced and enforced.

In Switzerland, the work of Anton Stankowski earned a great deal of

respect for the "new typography." His work developed further and gained

fame in the 1950s under the name "Swiss typography." The first generation

of this kind of Swiss typographer included Max Bill, Richard P. Lohse,

Max Huber, and Emil Ruder.

In addition to the Swiss designers, the former head of the Bauhaus

typographical studio, Herbert Bayer, worked in the United States with great

success. The link between the strict dogmatism of the sans serif face and

aspects of American design led to an interesting form.

The loss of strict grotesque typography and the innovative work from

the United States, with a highly pictorial development in the use of letters

and text combined with photographs, led to more successful graphic

design. It increasingly became a matter of designing total concepts and

identity programs.

In 1949, Eduard Hoffmann, head of the Haas Type Foundry in München¬

stein, near Basel, was planning a new grotesque typeface. His model was

Schelter Grotesk, the official Bauhaus typeface. Swiss designers at that time

were making increasing use of Berthold's Akzidenz Grotesk, and Swiss typog¬

raphy was becoming known throughout the world. Eduard Hoffmann

knew exactly how the new typeface should look and entrusted the design

to Max Miedinger in Zurich, who was an expert on grotesque typefaces. His

sketches were passed to the Haas Type Foundry's in-house punch-cutting

works for casting in lead. In 1957, the name of this project was New Haas

Grotesque, but Stempel published the new typeface in i960 under the

name Helvetica.

With the arrival of photosetting, typography and design gained unre¬

stricted freedom of movement. For the first time there was access to the

most diverse typefaces. This change enabled even better visualization of

the content, and words and text images could be set closer together.

In 1973, Günter Gerhard Lange, type director of Berthold and redesigner

of Akzidenz Grotesk, described the introduction of this redesigned font:

"In this work, the basic proportions of the well-loved Akzidenz Grotesk

semi-bold have been used to determine the average length and individual

shapes. Naturally, the family similarities between the individual styles had

to be taken into account, as did the mood and fashion of the times." The

fashion ofthat time included the then brand-new Helvetica by Max

Miedinger, as well as competing new faces like Adrian Frutiger's Univers

and Konrad E Bauer's Folio.

Helvetica was never intended to be a full range of mechanical and hand-

setting faces. When Univers, the highly extended typeface family by Adrian

Frutiger,was successfully launched, Stempel was forced to redesign the

whole range according to the method Frutiger initiated, using numbers for

the different members of the Helvetica family. Helvetica was just what

designers in the early 1970s were looking for. In 1982, Stempel introduced

New Helvetica.

There is a broad interest in the history of typography today, which I hope

will extend to the future. We are still looking for new opportunities and

"the mood and fashion of the times." The question is, has the ideal typeface

been invented yet? That is for you to decide.

Most striking, I find, is that type designers, with their wonderful eye for

detail, can determine such a great difference in character. There is a world

of difference, for instance, between Caslon (1725) by William Caslon and

Baskerville (1754) by John Baskerville. Or compare Berthold's Akzidenz

Grotesk (1899) with Paul Renner's Futura (1925). The page looks completely

different, and, as a reader, you perceive the message differently, too. The

choice of typography and the application of the graphic designer can trans¬

port you to another world.

A Small Selection of Type Designers with an Eye for Detail

Claude Garamond: Garamond

The French Renaissance Antiqua sees the light of day. Claude Gara¬

mond was born in 1480. He learned his craft very early from his father

and others in the family circle. Garamond claimed he could cut printed

stamps in Cicero size (12 point) at the age of 15. In the first quarter of the 16th

Century, French type cutters and printers were the counterparts of Italian

creators of the Renaissance Antiqua. Aldus Manutius and Francesco Griffo's

Antiqua typefaces came to France, along with those of Pietro Bembo.

Claude Garamond is one of the founding type cutters and casters of

the French Renaissance Antiqua and Italica. It was during his era that

12

Cees W. de Jong

THE LINOTYPE BULLETIN

the Caslon letter. It was the faee commonly in use uiitilaboul 1800... Franklin

adulimi and recommended Caslon's types, and his own office «a, equipped

with them."* Caslon thus penetrated to the Colonica! an early datc.and is ours

by right of inheritance, if not of origin. Of the American Gisions of today

the best are those which most closely follow the original. Unfortunately the

name in recent years lias been applied to a grcar variety of types,—юте of

them based on later cuttings of the Caslon foundry, others simply non¬

descript or bastard faces—with the result that there are many Casions now

extant which are not Casions at all in the true sense of the temi.

Linotype Typography Caslon Old Face is based directly upon the Hnglish

Cubrí Old Face, derived from the types of William Caslon himself. It pre¬

serves Caslon's many characteristic departures from mathematical precision,

which, while detracting from the "perfection" of design of individual letters,

contribute so largely to the variety and interest of the type when composed

in mass. In this issue of the Bullclm it is shown for the first time in full series,

from ii lo ,16 point, uscal with its related series of borders and ornaments, many

of which are likewise derived from Caslon originals.

•>i

1111 j luxa

¡. Ill |í I I It :l I I 1_

[.80]

ГНК UNMVKRSALITY OF CASLON OLD FACE

W,lk * Biosrafhictl Sote ou William Смііоы I

II' Л ѴОТЯ «mid be taken among Kngli*h- Show any nun » properly dnigncd раке «et in

u

rcspend to il> lieiuiy, cien (huu|¡h he Ire » lay¬

man knowing nothing uf lype tcihnicalitie».

There it »ornclhing about ÌI that inevitably "gett

TI' Л VOTE could 1-е taken among Engliih-

I ігкакіпб printer» today as ю what type ihey

would chenue first in filling out a tontpoung-

niiim, there it no

ail)' ««her face, it ha» lictomc 'Standard" with

ihc modern print »hop—a type without which

Ihc printer would nut cuntîdcr himself properly

equipped, ll І1 the one type thai t» common, in

uric derm ur another, to all njcnpaMrig-roajnu.

There are types which are unquestionably more

graceful and "elegant" than Cation, type* which

are better adapted—in Ihenry, « 1««—to ihc

Condition! ol printing luday ( yet Caslon remain»

more Widely uied than any of them. It cun-

linue» to hold iti place in Ihc face of all pretent-

Jay competition. Why in the «of What it there

ihoul thi> type, now over two hundred year» old,

!I1.1t give» it it» al muti unlvenal appesii1

Cation— and it tvhould be understood in whal

folloni I hat the rume referí to Casio«'» old ttyle

type» in their pure form, not to the many m¡*-

cellaneout Casions of more recent vintage—¡t,

lint of all, the mud »«•/■' type the prinler hat.

II .an lie employed for a greater variety of |>ur-

|hki than any other. There it practically no

form of printing that cannot he tet, and »et well,

in it. Л modem criik hat said of it thai "if all

other Knglith typet Were luJdcnly Ю disappear

from the face of ihc earth, it could tutccufully

batr alone the burden of modern print."

To ilk utility of Cation iwu factor» contril tute

in • i|".il proportion. 'Ihc lint it the beauty nf

ihc face, anJ ihe iccund Ut Irrihilily. These

•|uilirici are, of couru-, commun lo all toax-ful

type face», but the manner of ihcir comUnaticm

in Cation hat tumcthing about it that nukes a

peculiar appeal to Ihc Anglo-Salon Urate.

Cailun it nut one uf the mulled "urnamen-

lai" type», ІНІІ it it undeniably a lieauiiful type.

hold of you"—»trength, power, dignity, i

est. It has ¡л ¡I wmcthlng of the univcnul

quality of great art —ihc quality thai lift) "

above (he laues anJ fathiont of any pirriud and

make» it permanently alive and vital.

There i» nothing "highbrow" about it, how¬

ever. Il it a common-tense, practical beauty thai

appeals a» ttrongly to the layman as lo the аліи.

Nor ¡s il a beauty that oUrudca iltelf, at i- so

oflen the ca»e with ornamental typct| ІІ dun not

put iltelf forward at the capente of legibility.

1'ur Caslon, alune all el«, was "made tu

read." Its legibility i» ІН outstanding quality.

The eye can follow il for page »fier pige ■"■'"-

out becoming faligucd and wilhuul »«)' icnte uf

memulón)-. It ha» not ihc précité mail.с пи l ici I

regularity of many types of lodai/, nor it it »o

good in the dctign uf individual letters. There

are all manner of variation» in it—»u much to

that cernili letter» slnunl appear ■! lime» Io Ik

wrong fotti— but Ihc variai ion» »re largely de¬

liberate and conlrilnilc lo the intere« »ml read¬

ability of ihe printed page. The Irue let! of »n>

type, apart from ihnsc lypet whk'h »re purely

ornamental — Ihe teil whiih finally de I ermi net

id »ucccis or failure —is ils ІехШІИу allea com

¡HiirJ tu meni and Culoflj lo our Л ligi »-Su on

iJtie», patte» thi» ini heiter than any other. It

itlhis comliination of qualities, whkh hascaiucd

it to turvivc where many type» thai were theo¬

retically "toter" have been forge*««, »«d

which give»il Unlay iticmincnt commercial value.

All (he qualilie» named—utility, beauty, legi-

biliiy—trace luck eventually, »• with »ny »rti»-

lic pntdoction, tu the man behind the work, and

[.89]

Roman capitals and Carolingian lowercase letters were brought together. In

centralized France, conditions were more favorable for making progress in

typography and letterpress than in Italy or Germany. Claude Garamond

gained real fame and his position as royal type caster after the 1543 Greek

publication Grecs du Roy, which King Francis I, a supporter of letterpress,

engaged him to cut. The first Antiqua that can be confidently dated and

attributed to Garamond was a large typeface, Gros-Roman, which appeared

in an edition of the works of Eusebius and other publications by Robert

Estienne in 1544.

After 1545, title pages show, Garamond was also a publisher, both in

his own right and together with Pierre Gaultier and Jean Barbé. Examples

of a modern Garamond in use today are Jan Tschichold's Sabon and, even

better, Sabon Next by Jean François Porchez.

William Caslon: Caslon

Caslon, a man with a versatile mind. William Caslon was born in

Cradley, Worcestershire, in 1692. At the age of 13, he was apprenticed to an

engraver in London. In 1717, he became a citizen of London, where, the

year before, he had set himself up as an independent engraver. Two years

later, he opened his own type foundry.

It was the bookbinder John Watts who engaged Caslon to design and

cast typefaces for his book covers. One of these books then caught the

eye of William Bowyer, a well-known London printer. The two became

friends, and Bowyer introduced Caslon to other London printers. This was

the start of one of the most successful type foundries in England. Initially,

Caslon was supported financially by Watts, Bowyer, and his son-in-law

James Bettenham, also a printer.

In 1720, his first year of business in the type foundry, he produced a new

typeface for the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge to be

used for a Bible in Arabic. Having finished the Arabic script, he printed a

sample page so that he could sell the new typeface to other printers. On this

sheet was his name, William Caslon, in roman letters designed specially for

the purpose. This new typeface design was the beginning of the popular style

we now know as Caslon Old Style. Following this style, Caslon cut a num¬

ber of non-roman and exotic styles, including Coptic, Armenian, Etruscan,

and Hebrew. Caslon Gothic is his version of Old English, or black letters.

All these typefaces had appeared before Caslon published the first and

extensive catalog for his type foundry in 1734, presenting a total of 38 type¬

faces. Caslon's type foundry moved to the famous Chiswell Street, where

Caslon's son and several generations of the family after him ran the busi¬

ness for more than 120 years. In 1749, King George II made Caslon a justice

of the peace for the county of Middlesex. He retired and died at his country

house in Bethnal Green in 1766, aged 74. His was a success story of an

extraordinary engraver.

John Baskerville: Baskerville

A quest for the best result. John Baskerville (1706-1775) started cutting

and casting his own typefaces around 1754. He was influenced by the letter¬

ing of stonemasons, as were other English type designers who developed

faces we regard today as typically English: grotesques and Egyptians, which

appeared elsewhere in the Industrial Revolution. Baskerville had to imagine

what was of great importance for him: how his typefaces would be printed

and what they would look like. Paper, ink, typefaces, and printing machines

therefore all played equally important roles for him.

In 1750, John Baskerville established a paper mill, type foundry, and print¬

ing business. He then came up with the idea of coated paper. After a great

deal of painstaking work, in 1754 he presented his first typeface. In 1758, his

famous edition of Milton's Paradise Lost was produced, a one-man work of

art, or Gesamtkunstwerk, before the term existed. Baskerville also worked as

a printer for the University of Cambridge, where he was promoted director

in 1758. One of his most famous publications is Juvenalis (1757)-

The spacious typefaces Baskerville designed; the open way of typeset¬

ting, increasing the spacing between words and lines; the width on the

page; and the use of coated paper and very black ink gained him renown

throughout Europe. After his death, a large part of Baskerville's typeface

material, the secret ink formula, and the manner of producing coated

paper were sold to the Frenchman Caron de Beaumarchais. Between 1785

and 1789, he printed 70 volumes of Voltaire using the Baskerville letters.

Baskerville would have been very happy with the result.

Giambattista Bodoni: Bodoni

"Plenty of white space and generous line spacing, and don't make

the type size too miserly. Then you will be assured of a product fit for

a king."—Giambattista Bodoni

He has been called the king of printers and the printer of kings.

Bodoni's reputation is based on the Manuale tipografico, a compilation

The Ideal Typeface

■3