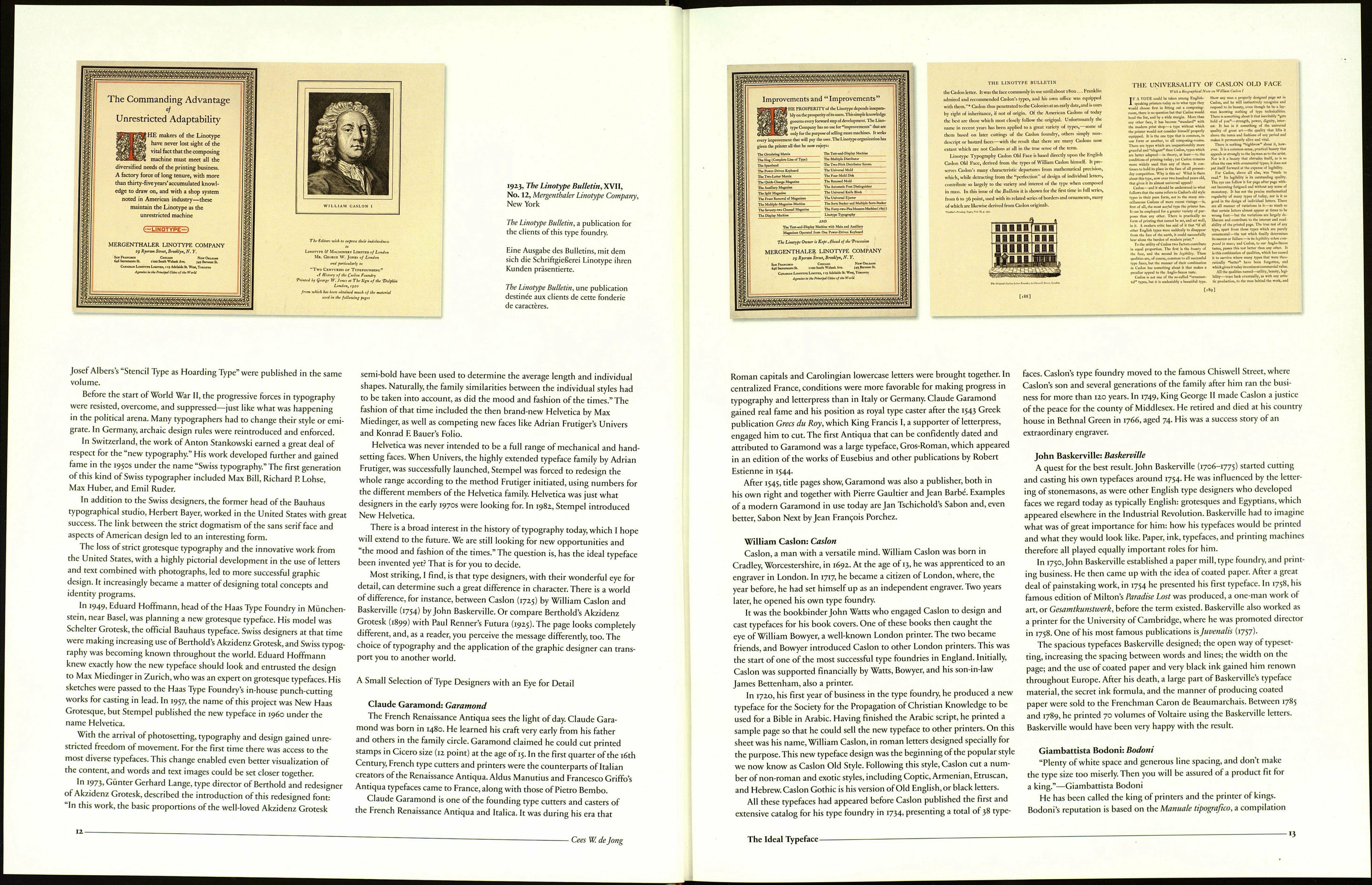

1923. The Linotype Bulletin, XVII,

No. 12, Mergeu thaler Linotype Company.

New York

An initial T, a clear accent on the page—

the perfect beginning to any page.This

one is based on the work of William

Caslon.

Initialen setzen klare Akzente - ein per¬

fekter Auftakt für eine Seite oder einen

Absatz. Diese T-Initiale entstammt dem

Werk William Casions.

Une lettrine T, un accent net sur la

page—rien de tel pour un début. Celle-ci

est basée sur le travail de William Caslon.

• Cees W. de Jong

INTRODUCTION

The Ideal Typeface

by Cees W. de Jong

What kind of character should letters have, and which aspects

ofthat character should their content convey? Is the customer a newspaper,

are you designing a letter on your own initiative, just "for fun," or does

a company need a new house style for its communications strategy?

New innovations have introduced radical changes in typography and

printing, which had seen only slight modifications since the 15th Century.

Craftsmanship was steadily supplanted by machinery, and the increasing

demand for printing required more and improved equipment. Work¬

manship became less important, as supervisors and assistants could now

perform tasks that in the past had required hundreds of skilled workers.

Our script has evolved from the flow of writing. Naturally, this eventually

prompted the development of the serif in printed letters. The amazing

thing is that typography developed for hundreds of years internationally,

but only with serif typefaces. The first examples of the new sans serif style

did not appear until 1816 in England.

In the 19th Century, there was a general degeneration of appreciation

for typography, design, or quality in printing material. Printers produced

pages with numerous type sizes and combinations of any typefaces available

in the shop. Except for an occasional superficial imitation of traditional

typography, there was little indication of any concern for page organization

or well-designed typefaces.

In 1951, M. R. Radermacher Schorer, in his Bijdrage tot de Geschiedenis

van de Renaissance der Nederlandse Boekdrukkunst (Contribution to the History

of the Dutch Printing Arts), gave a dismal summary of the period: "When

we compare the 19th-century book to the incunabula, the type is pallid

and without character, often damaged and badly printed; the arrangement

is confusing; the color is faded; the paper is of bad quality; the spine is

covered with gold stamping without beautiful ornaments ... and thicker

paper is used to make the book look larger than it actually is."

Drastic changes in typography and technology occurred in the 19th

Century. For 400 years, the lead setting system had limited the options;

the arrival of new technology changed typography, design, and printing.

New styles and traditions emerged.

After the Arts and Crafts Movement of William Morris and, later, Peter

Behrens, developments were divided into the subjective-expressive and

functional, or elementary, schools of thought.

The expressive position is reflected in the work of Rudolf Koch,

who sought the path of innovation in returning to individualism and

preindustrialization.

In January 1898, two companies, Berthold and Bauer & Co. of Stuttgart,

presented the Akzidenz Grotesk font in advertisements in the Deutscher

Buch und Steindrucker. The font was therefore already more than 20 years

old in the heyday of Constructivism, when movements such as De Stijl,

Bauhaus, and Dada adopted the face to great effect. It was present at the

birth of "Swiss typography" as its major typeface. Akzidenz Grotesk still

has a highly visual quality, reminding us that type does not have to be

uniform to be readable and attractive; on the contrary, it is the differences

between characters that make them legible.

Functional typography was developed primarily by designers in the

Soviet Union, Germany, Hungary, and the Netherlands. There was a desire

for a better social, cultural, future-oriented design that reduced ornamenta¬

tion and the choice of typographical elements. Sans serif typefaces, lower¬

case letters, and asymmetrical spacing were major characteristics of this

"new typography."

Eric Gill was commissioned by Bristol bookdealer Douglas Cleverdon

to paint a sign with sans serif lettering. Stanley Morison, artistic adviser to

the Monotype Corporation, who was visiting Cleverdon, noticed the sign,

and became convinced that Gill could design a similar sans serif face for

Monotype. Until then, Gill had used only capitals. As usual, the first draw¬

ings of the lowercase letters were quite different from the face that was

finally cast. However, when Gill Sans first appeared, toward the end of the

1920s, it was not exactly what the British print establishment had been

waiting for. Its muted reception in the year 1928 was similar to that of Futu¬

ra in Germany the year before; Paul Renner's design had been called a fash¬

ion that would soon be forgotten.

Futura is a timeless, elementary typeface. In i925,Jan Tschichold pub¬

lished a special edition of Typographische Mitteilungen entitled "Elementary

Typography." It was here that he first formulated his attempts to create a

new typography."Of the typefaces available, the grotesque or block faces

fulfilled the needs of the new typography best, as they were simple

in design and easy to read."

At the same time, Paul Renner's design for a new grotesque style based

on Constructivist principles was in progress. Renner based Futura on

simple, basic forms: the circle, the triangle, and the square. However, his

affinity with books and typography prevented him from casting aside

tradition in favor of a new dogma. The first samples of the new style made

their appearance in 1925.

In 1926, Bauhaus leader László Moholy-Nagy wrote in Bauhaushefl 7:

"Since all existing grotesque book styles lack basic style, grotesque still

has to be created." Herbert Bayer's essay "Attempt at a New Typeface" and

The Ideal Typeface

и