Шіепсі7 Oei-scilien.

БЕЦКОЙ

Поти

ТАЖЕ

йпн

Schmale antihc Scelctl.

ШИШЕЙ ДРШШШЬ БРЕИЕНЪ ЗШЖШП, 4ШДЕМІЯ

КЛКСИЫНЛІЛНЪ ВЕЛИКОЕ КНЯЖЕСТВО

ЛЮТТИХЪ ВОЛОКОЛАЫСКЪ ЧЕРНЫШЕВЪ БОРОДИНО

МИНСКЪ АФРИКА МОСКВА ГРОДНО КАЛѴГА

ЯРОШВЪ ШПІІВЬ БРОННИЦЫ

ЖІОКЪШРШЕ

КОВІІСКВА

collaborate, resulting in the establishment of the American Type Founders.

Their first type specimen, a heavy tome of more than 800 pages, appeared

in 1896.

In the Hauptprobe, you can see that toward the end of the 19th Century

special attention was paid to titles and subheadings, which were presented

with colorful settings, in many hues, and with lavish use of ornaments,

many of them very lovely. All this must have stemmed from striving to

compete with lithography—a successful effort, it seems, as these specimens

are sometimes referred to in the catalogs of antiquarian booksellers and

auction houses as chromolithos, although the relief on the back clearly

indicates letterpress.

In the early 19th Century, at the age of 66, the French letter engraver

Henri Didot did the almost impossible by engraving a microscopically tiny

2.5-point type, the smallest ever made. Later, the punches and matrices

ended up in the possession of Johannes Enschedé & Zonen, who, in 1861,

printed the Dutch constitution, a booklet measuring 4.5 x 6.5 centimeters.

I bought one of the last copies at the Haarlem train station. Various firms,

including Enschedé, were selling off their remainders on the occasion of an

antiquarian book fair. Henri Didot was also the inventor of the polyamatype,

a mold with which you could cast up to 120 small letters at a time. His

cousin, Pierre Didot, who had inherited a printer's press, also developed

into a letter engraver. In 1819, his first specimen, Spécimen des nouveaux

caractères de la fonderie etc., was published. The texts are poems from his

own hand.

In 19th-century specimens from countries such as Germany, the Nether¬

lands, and America, the same ornaments, wood engravings, and such are

often found. You might wonder whether all ofthat was actually organized,

with contracts and royalties. Stereotypy had been in use for some time

already, and, from roughly 1840 onwards, it was easy to copy things galvani-

cally. Copyright was not protected in those days. (Mind you, I read some¬

where that, these days, 80 percent of software is used illegally ...)

Specimens including first showings of types are especially valuable to

collectors. I have one of Centaur, for example, with a preface by the design¬

er, Bruce Rogers; one of van Krimpen's Lutetia; and one featuring Carder

(1966), the first text letter designed in Canada, by Carl Dair.

One also, unfortunately, comes across type specimens on poor-quality

paper. Some paper from the second half of the 19th Century has failed to

survive the ravages of time and crumbles between your fingers. Sometimes

the quires of books were not sewn but stapled onto a linen strip. This

method may have been cheaper, but it was certainly not stronger. After all,

the staples rust. Type specimens weighing kilos, even very expensive ones,

were sometimes bound in a paper binding. The large Imprimerie Nationale

specimen, for example, was bound in fine, delicate glacé paper—which is

asking for trouble.

But damage can also be the work of vandals. Sometimes pieces have

simply been cut out of specimens, despite the request at the front of the

book not to do so! A good bookseller will check the volume for such

damage and mention it in his catalog. Jammes uses the nice term fenêtres

(windows) for such holes.

I have an extensive specimen from Gebroeders Hoitsema in Groningen,

with the date 1897 on the cover. The unusual thing about this specimen is

that the year of purchase, the supplier, and the weight are noted for each

type. A clear majority of them are from German foundries, which is per¬

haps not so astounding, in view of the geographical location. It would be

interesting to find out whether the German foundries sent their represen¬

tatives directly to the Dutch printers. In a few cases, an agent is named:

Klinkhardt (Van Meurs), Huck (R van Dijk), and so forth. It is also interest¬

ing to see the mention of smaller Dutch foundries such as G. W van der

Wiel & Onnes and De Boer & Coers. In 1869, the Hoitsema brothers also

purchased from Reed and Fox, the late R. Besley & Co, London (two-line

English Courthand).

Old specimens from printers are rare. I'll name a few firms from

which I have old copies: Bricx in Ostend (around 1787); H. Martin &

Сотр. (1829), J. Ruys (1908), Pieper & Ipenbuur (1828), and the Stads en

Courant drukkerij (1834) in Amsterdam; M. Wijt (1828) and J. W van

Leenhoff (1837) in Rotterdam; B. Henry (1828) in Valenciennes; the

university printer Johan Frederik Schultz (1805) in Copenhagen (the

second copy, in Copenhagen's Royal Library, was mislaid years ago!);

De Bachelier (1842) in Paris; Michael Lindauer (1825) in Munich; Osval-

da Lucchini (1853) in Guastalla; Rand and Avery (1867) in Boston—then

the second-largest printer in America—and John F. Trow (1856) in New

York (from whom I have an example of "rainbow printing," a kind of

iris printing).

One showpiece in my collection is a specimen from around 1847 from

the Groningen type foundry Van der Veen Oomkens & Van Bakkenes. In

the back, printed in color, are "Plates for Congreve printing." This system

46

Jan Tholenaar

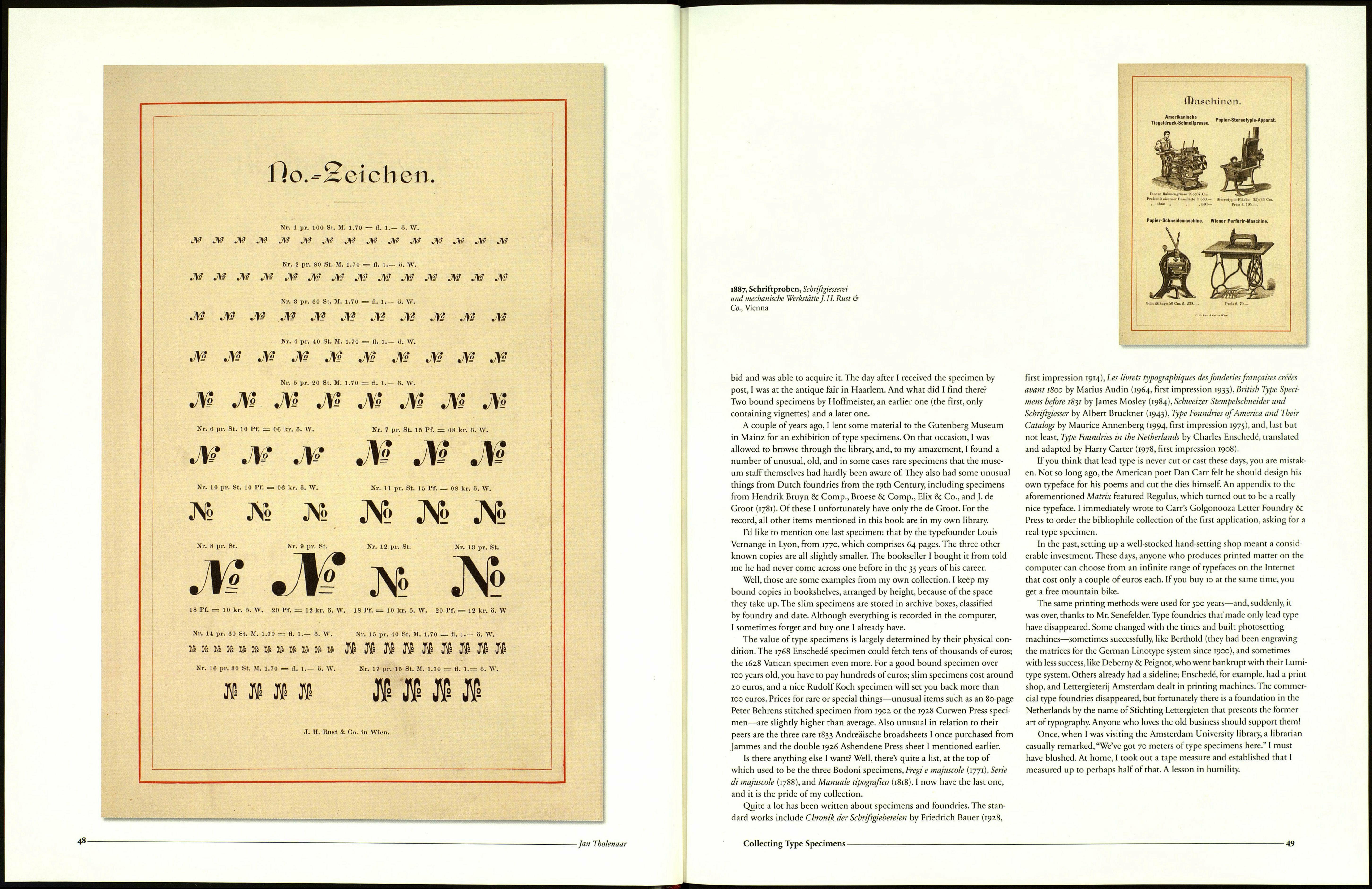

1887, Schriftproben, Schriftgiesserei

und mechanische Werkstätte J. H. Rust &

Co., Vienna

"To Russia with Love." These samples for

export markets show faces for producing

posters, as well as letter and number

characters.

„Liebesgrüße nach Moskau" - Muster

für den ausländischen Markt mit Plakat¬

schriften, Versalien und Numerozeichen.

« Bon baisers à la Russie ». Ces échan¬

tillons pour les marchés d'exportation

présentent des polices destinées à la

fabrication d'affiches ainsi que des

caractères de chiffres et de lettres.

was intended for printing stocks and bonds in more than one color at a

time (in letterpress). This foundry, established in 1843 by Alle van der Veen

Oomkens, was taken over in 1857 by Onnes, De Boer & Coers and moved

the following year to Arnhem. In 1894, Enschedé took over the matrices.

I purchased a compiled Enschedé type specimen from the end of the 19th

Century that contains 145 wonderful pages by these type founders from

Groningen and Arnhem.

One special specimen from the United States is the 1882 Bruce. It is

comparable with the Derriey in its enormous range of borders and deco¬

rated letters. There is also a vast array of lovely electrotyped ornaments

illustrating professions, shop interiors, trade articles, and so forth. Bound

in is a sizable work by De Vinne on the invention of book printing.

Especially unusual are the broadsheet type specimens, all on one sheet.

The oldest surviving specimens are largely broadsheets. In the 20th Centu¬

ry, Monotype, for example, produced some creditable work in this format.

Highlights include the sheets Stanley Morison made for Monotype, the

Pelican Press, and the Cloister Press.

In the 1930s, the firm of Bom was used when the material from a

printing firm had to be auctioned, generally due to bankruptcy. I have

75 auction catalogs with the auctioneers' notes. The type up for auction

was printed in the catalog—in a single line and without the name, to be

sure, but these are nonetheless type specimens.

If you ask anyone which is the oldest surviving printer in the Nether¬

lands, they will probably say Enschedé. But it is, in fact, Van Waesberge.

You can read the company history in a type specimen from 1918. Van

Waesberge was established more than 400 years ago in Rotterdam.

According to a specimen from 1852, N. Tetterode, later Lettergieterij

Amsterdam, also started in Rotterdam. In part two of this specimen, from

1856, Tetterode calls himself an Amsterdam type founder. It was there that

he took over the De Passe & Menne foundry (I have their 1843 Proeve van

drukletteren specimen) in Bloemgracht. In the first supplement, he has

pasted his own name over the name of De Passe & Menne. In his early

specimens he still used the classic example text, which can also be seen in

18th-century specimens by Caslon, Fry, Wilson, and Bodoni: "Quousque

tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra?'

Setting-machine manufacturers also often produced very thick type

specimens: Linotype, Intertype, Monotype, and Ludlow. I have a specimen

from Typograph. These generally use typefaces licensed from foundries.

Plakofschi?ißfen.

Nr. loie. Uln. ISO Stuck. Per Slock In Hola 11 kr. Par Sttl<-k !■ Mr..In,; 14 kr. 0. W.

E3QTEPI

He. lOie. Hin. Ido Siil.k. Per Piti, k in П.І. 14 1er. Per BtGek 1» H.arlni ВЙ kr.

1. U. Itu.l . Ce. la Win.

One coincidence: At one point I only had three slim specimens by

Heinrich Hoffmeister, who started a type foundry in 1898 in Leipzig. So

when a specimen in book form came up for auction in Berlin, I put in a

Collecting Type Specimens

47