A Theory of chisels and pens, which gave it its more characteristic

Illumination and finished form. If we use chisels and pens pro¬

perly we shall get a similar result—not absolutely

the same—for no two chisels or two hands can

be quite the same—but closely resembling it and

belonging to our own time as much as to any

other.

The essential form of the “Roman” A is a purely

abstract form, the common property of every rational

age and country,1 and its characterisation is mainly

the product of tools and materials not peculiar to the

ancient Romans.

But when there is any real complexity of form

and arrangement, or sentiment, we may reasonably

suppose that it is peculiar to its time, and that the

life and virtue of it cannot be restored.

It was common enough in the Middle Ages to

make an initial A of two dragons firmly locked

together by claws and teeth. Such forms fitted the

humour of the time, and were part of the then

natural “scheme of things.” But we should beware

of using such antique fantasies and “organisms”;

for medieval humour, together with its fauna and

flora, belong to the past. And our own work is only

honest when made in our own humour, time, and

place.

There are, however, an infinite variety of simple

abstract forms and symbols, such as circles, crosses,

squares, lozenges, triangles, and a number of Alpha¬

bets, such as Square and Round Capitals, Small

Letters—upright and sloping—which—weeded of

1 It has even been supposed that we might make the inhabit¬

ants of Mars aware of the existence of rational Terrestrials, by

exhibiting a vast illumination—in lamp-light—consisting of a

somewhat similar form—the first Proposition in Euclid.

162

archaisms—we may use freely. And all these forms A Theory of

can be diversified by the tools with which they are Illumination

made, and the manner in which the tools are used,

and be glorified by the addition of bright colours and

silver and gold. Very effective “designs” can be

made with “chequers” and diaper patterns, and with

the very letters themselves. And I have little doubt

that an excellent modern style of illumination is quite

feasible, in which the greatest possible richness of

colour effect is achieved together with extreme

simplicity of form.

“filigree, or pen-work, illumination”

(See also pp. 171-4, 175, 184-6, 411, 414-15;

figs. 79, 92, 125-26, 150, 188-89; Plates XI,

XIII, XIV, XVII.)

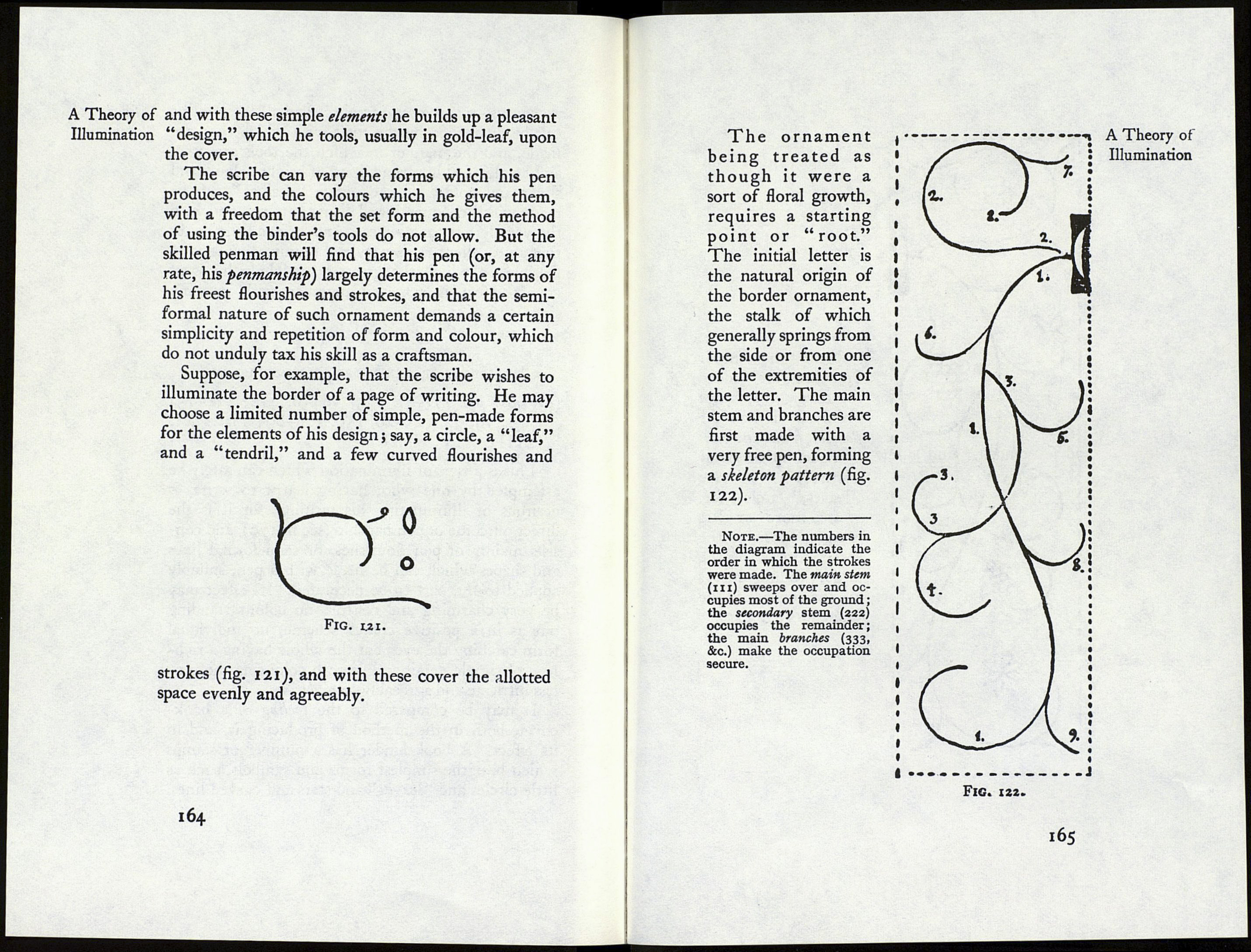

This is a type of illumination which can safely be

attempted by one who, having learnt to write, is

desirous of illuminating his writing; for it is the

direct outcome of penmanship (see p. 170), and con¬

sists mainly of pen flourishes, or semi-formal lines

and shapes which can be made with a pen, suitably

applied to the part to be decorated. Its effect may

be very charming and restful: no colour standing

out as in a positive colour scheme, no individual

form catching the eye ; but the whole having a rich¬

ness of simple detail and smooth colouring more or

less intricate and agreeably bewildering.

It may be compared to the tooling of a book-

cover, both in the method of producing it, and in

its effect. A book-binder has a number of stamps

which bear the simplest forms and symbols, such as

little circles and “leaves” and stars and curved lines,

163