Inscriptions together, and approximately equal in length, and

in Stone form a mass (see fig. 205). Absolute equality is

quite unnecessary. Where the lines are very long

it is easy to make them equal; but with lines of

few words it is very difficult, besides being deroga¬

tory to the appearance of the Inscription. In the

“Symmetrical” Inscription the length of the lines

may vary considerably, and each line (often com¬

prising a distinct phrase or statement) is placed in

the centre of the Inscription space (see fig. 204).

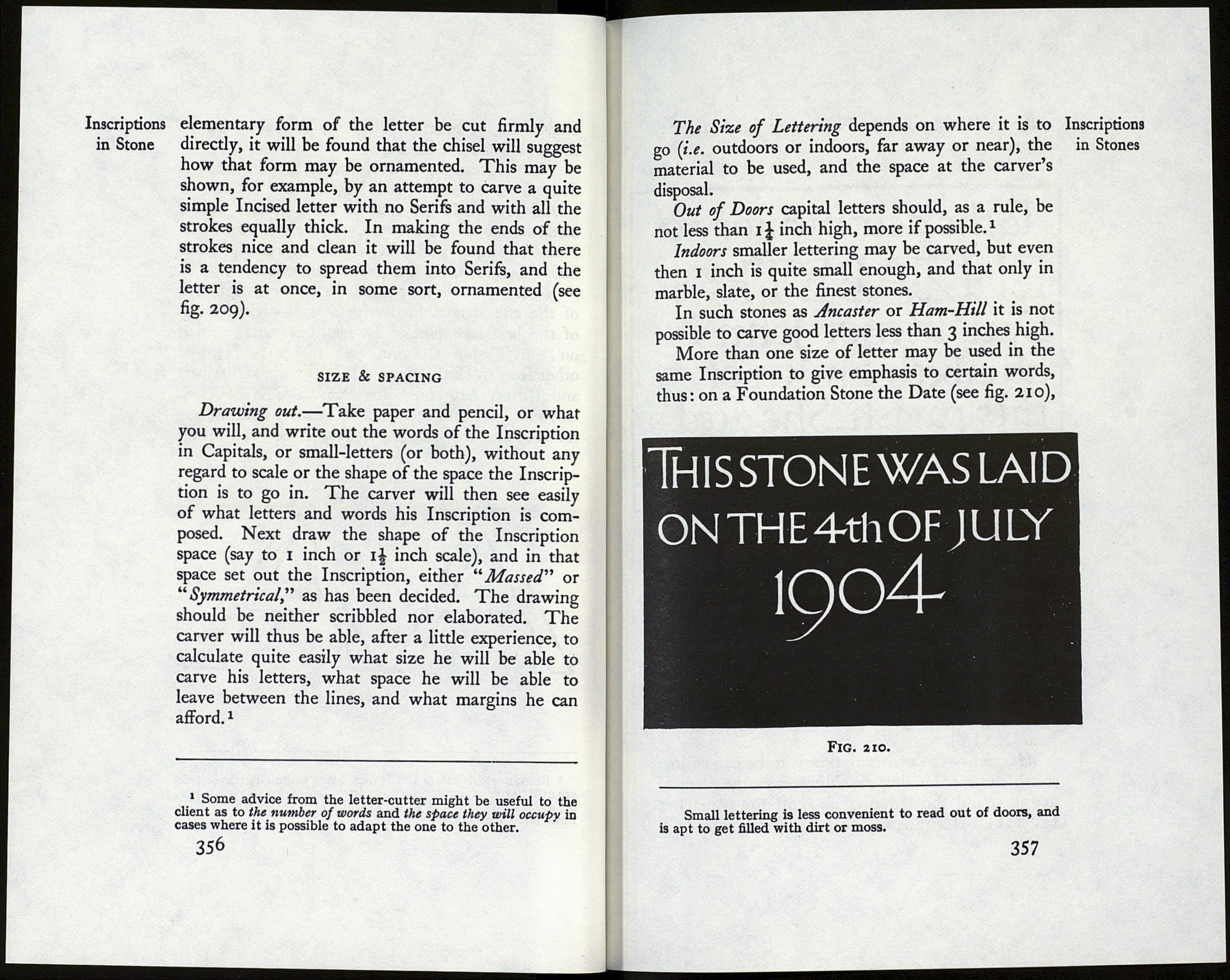

Short Inscriptions, such as those usually on Tomb¬

stones or Foundation Stones, may well be arranged

in the “Symmetrical” way, but long Inscriptions

are better arranged in the “Massed” way, though,

sometimes, the two methods may be combined in

the same Inscription.

THE THREE ALPHABETS

The Roman Alphabet, the alphabet chiefly in use

to-day, reached its highest development in Inscrip¬

tions incised in stone (see Plate I).

Besides ROMAN CAPITALS, it is necessary

that the letter-cutter should know how to carve

Roman small-letters1 (or “Lower case”) and Italics,

either of which may be more suitable than Capitals

for some Inscriptions.

Where great magnificence combined with great

legibility2 is desired, use large Roman Capitals,

1 With which we may include Arabic numerals.

1 It should be clearly understood that legibility by no means

excludes either beauty or ornament. The ugly form of “Block ”

letter so much in use is no more legible than the beautiful Roman

lettering on the Trajan Column (see Plates I, II).

354

Incised or in Relief, with plenty of space between

the letters and the lines.

Where great legibility but less magnificence is

desired, use “Roman Small-Letters” or “Italics.”

All three Alphabets may be used together, as, for

instance, on a Tombstone, one might carve the

Name in Capitals and the rest of the Inscription in

Small-Letters, using Italics for difference.

Beauty of Form may safely be left to a right use

of the chisel, combined with a well-advised study

of the best examples of Inscriptions: such as that

on the Trajan Column (see Plates I, II) and

other Roman Inscriptions in the Victoria and Albert

and British Museums, for Roman CAPITALS;

and sixteenth and seventeenth century tombstones,

for Roman small-letters and Italics.x If the simple

“A” with &

without

serifs.

Fig. 209.

1 Roman small-letters and Italics, being originally pen letters,

are still better understood if the carver knows how to use a pen,

or, at least, has studied good examples of manuscripts in which

those letters are used.

355

Inscriptions

in Stone