Special to here. A proper study of the art of typography

Subjects necessitates practice with a printing press, and prob¬

ably the help of a trained assistant.

To would-be printers, printers, and all interested

in typography, the easily acquired art of writing

may be commended as a practical introduction to

a better knowledge of letter forms and their decora¬

tive possibilities.

In this connection I have quoted in the preface

(p. xi) some remarks on Calligraphy by Mr.

Cobden-Sanderson, who, again, referring to typog¬

raphy, says—1

“The passage from the Written Book to the Printed

Book was sudden and complete. Nor is it wonderful that

the earliest productions of the printing press are the most

beautiful, and that the history of its subsequent career is

but the history of its decadence. The Printer carried on

into Type the tradition of the Calligrapher and of the

Calligrapher at his best. As this tradition died out in

the distance, the craft of the Printer declined. It is the

function of the Calligrapher to revive and restore the

craft of the Printer to its original purity of intention and

accomplishment. The Printer must at the same time be

a Calligrapher, or in touch with him, and there must be

in association with the Printing Press a Scriptorium where

beautiful writing may be practised and the art of letter-

designing kept alive. And there is this further evidence

of the dependence of printing upon writing: the great

revival in printing which is taking place under our own

eyes, is the work of a Printer who before he was a Printer

was a Calligrapher and an Illuminator, WILLIAM

MORRIS.

“The whole duty of Typography, as of Calligraphy, is

to communicate to the imagination, without loss by the

1 “Ecce Mundus (The Book Beautiful),” 1902.

ЗЗ2

way, the thought or image intended to be communicated

by the Author. And the whole duty of beautiful typog¬

raphy is not to substitute for the beauty or interest of the

thing thought and intended to be conveyed by the symbol,

a beauty or interest of its own, but, on the one hand, to

win access for that communication by the clearness and

beauty of the vehicle, and on the other hand, to take

advantage of every pause or stage in that communication

to interpose some characteristic and restful beauty in its

own art.”

Early Printing was in some points inferior in

technical excellence to the best modern typography.

But the best early printers used finer founts of type

and better proportions in the arrangement and spac¬

ing of their printed pages; and it is now generally

agreed that early printed books are the most beau¬

tiful. It would repay a modern printer to endeavour

to find out the real grounds for this opinion, the

underlying principles of the early work, and, where

possible, to put them into practice.

Freedom.—The treatment or “planning” of early

printing—and generally of all pieces of lettering

which are most pleasing—is strongly marked by

freedom. This freedom of former times is frequently

referred to now as “spontaneity”—sometimes it

would seem to be implied that there was a lawless

irresponsibility in the early craftsman, incompatible

with modern conditions. True spontaneity, however,

seems to come from working by rule, but not being

bound by it.

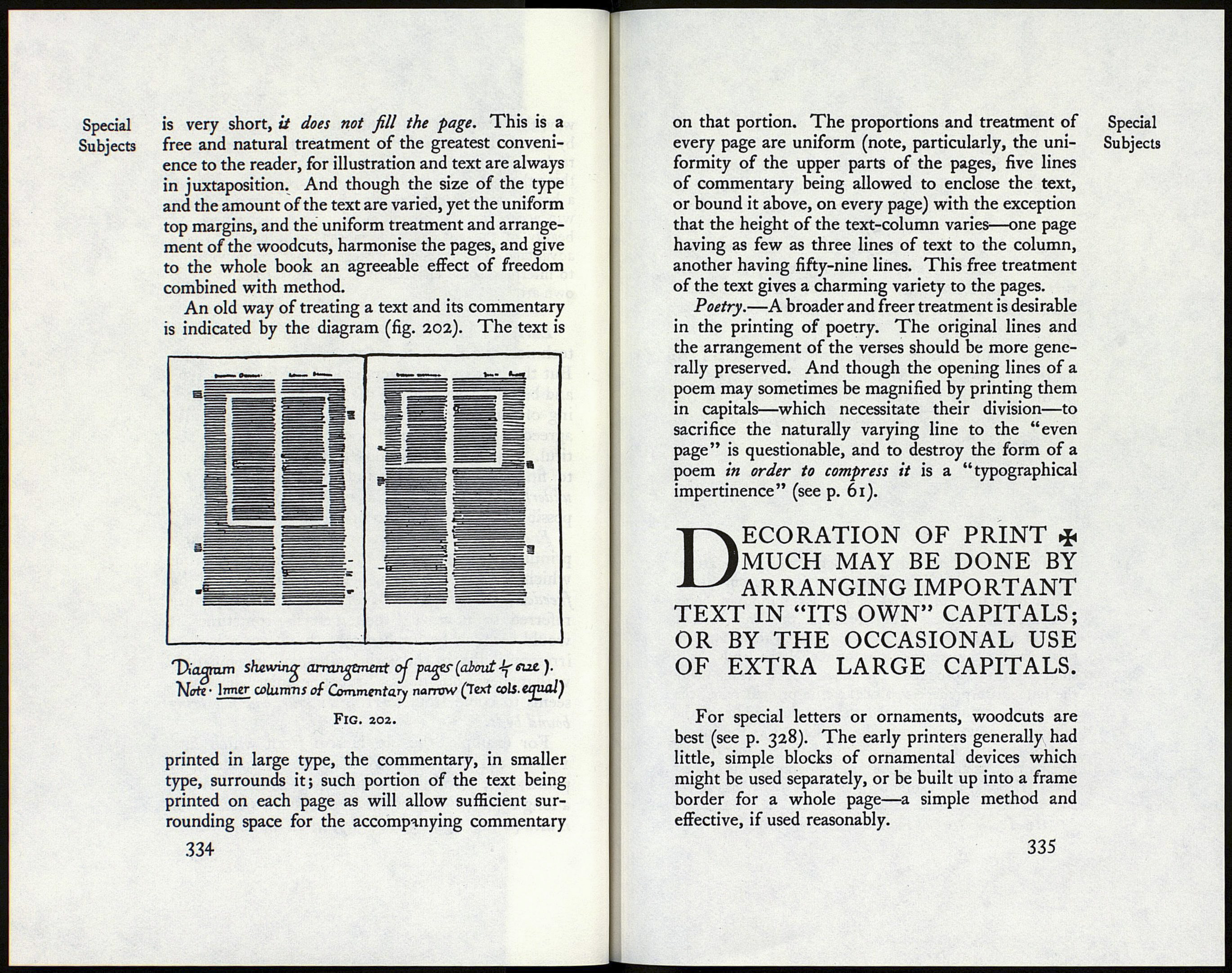

For example, the old Herbal from which figs.

135 to 141 are taken contains many woodcuts of

plants, &c., devoting a complete page to each. When

a long explanation of a cut is required, a smaller type

is used {comp. figs. 135 & 138) ; when the explanation

333

Special

Subjects