The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives

Contrasts of form, “weight,” and size.—These

are generally obtained by the use of large built-up

Capitals, together with a simple-written (or

ordinarily printed) text (fig. 187).

CONTRASTof ЮЖ

WeiGHT& S1ZE4

GENERAUX 00L01R

Fig. 187.

A marked contrast usually being desirable, the

built-up capitals (especially if black) are safest kept

distinct from the rest of the text (see fig. 197): if

they are scattered among the other letters they are

apt to show like blots and give an appearance of

irregularity to the whole. As a rule, the effect is

improved by the use of red or another colour (see

figs-91.93)-

Contrast of form—for decorative purposes—is

usually combined with contrast of weight (e.g.

“Gothic,” heavier, p. 300) or size (e.g. Capitals,

larger, p. 335).

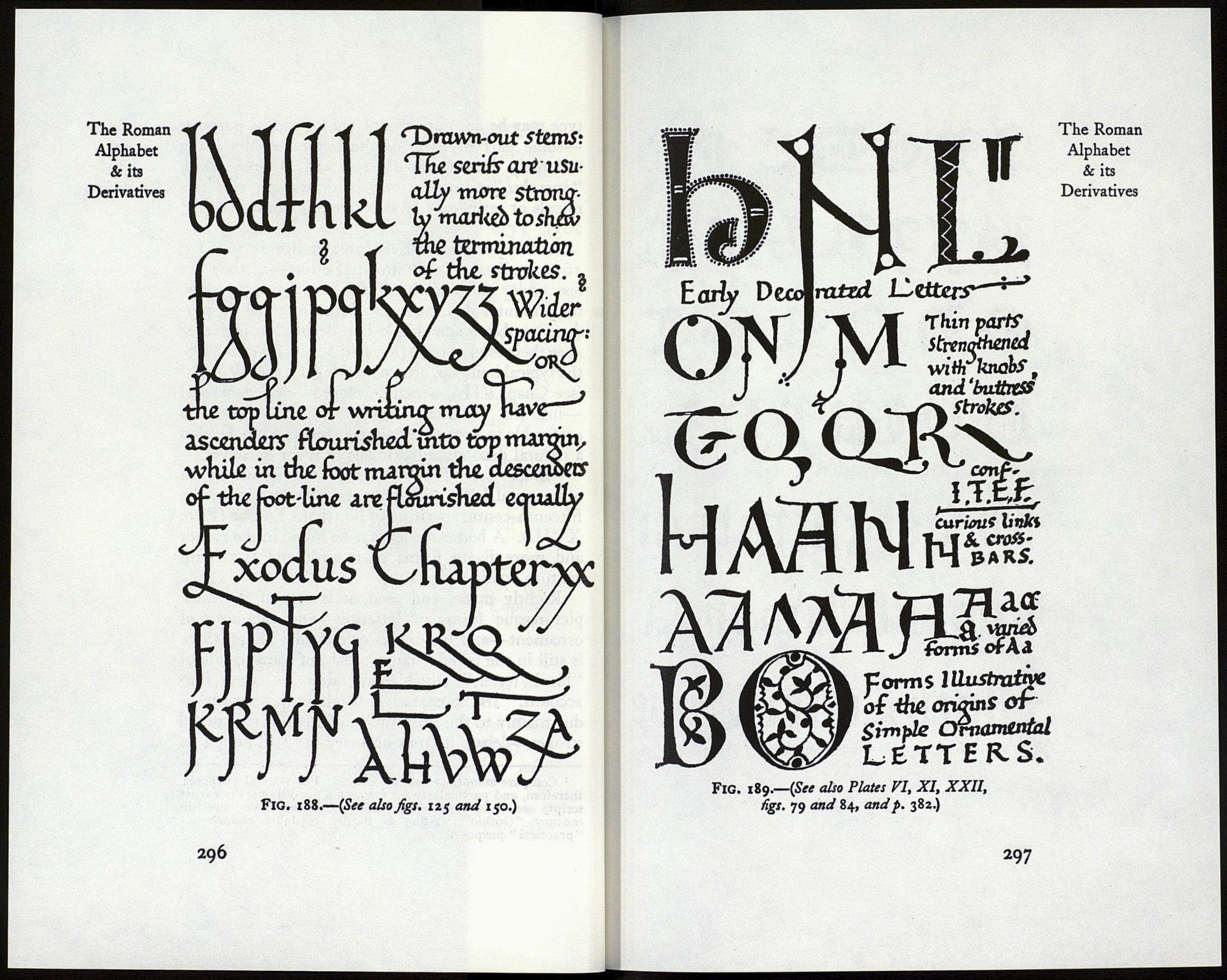

ORNAMENTAL LETTERS

(See Chaps. VII, Vili, X, XII, & pp. xxx, 215,

xxiv.)

To give ornament its true value we must distin¬

guish between ordinary occasions when simplicity and

directness are required, and special occasions when

elaboration is desirable or necessary.

The best way to make ornamental letters is to

develop them from the simpler forms. Any plain

294

type may be decoratively treated for special purposes

—some part or parts of the letters usually being

rationally “exaggerated” (p. 216). Free stems,

“branches,” tails, &c., may be drawn out, and ter¬

minals or serifs may be decorated or flourished (fig.

203).

Built-Up Forms.—Even greater license (see fig.

161) is allowed in Built-Up Letters—as they are

less under the control of the tool (p. 256)—and

their natural decorative development tends to pro¬

duce a subordinate simple line decoration beside or

upon their thicker parts (fig. 189 & p. xxiv). In MSS.

the typical built-up, ornamental form is the “Versal”

(see Chap. VII.), which developed—or degenerated

—into the “Lombardie” (fig. 1). Here again it is

preferable to keep to the simpler form and to develop

a natural decorative treatment of it for ourselves.

“Black Letter” or “Gothic,” still in use as an

ornamental letter (fig. 190), is descended from the

fifteenth-century writing of Northern Europe (Plate

XVII.). A better model may be found in the earlier

and more lively forms of twelfth and thirteenth

century writing (fig. 191).

Rightly made, and used, it is one of the most

picturesque forms of lettering—and therefore of

ornament—and besides its ornamental value, there

is still in the popular fancy a halo of romance about

“black letter,” which may fairly be taken into

account. Its comparative illegibility, however,—

due mainly to the substitution of straight for curved

strokes—debars it from ordinary use.1 Though its

1 Compare monotone and monotone. For general purposes,

therefore, and particularly for forming a good hand, the earlier

scripts are to be preferred (or the late Italian) : even twelfth-

century “Gothic writing is hardly readable enough for

"practical” purposes.

295

The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives