The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives

In the straight-stemmed capitals B, D, E, F, H,

I, L, M, N, P, R, and T, the first stroke is made

rather like an (showing the tendency to a zigzag)

the foot of which is generally crossed horizontally

by a second stroke making a form resembling j

on this as a base, the rest of the letter is formed

(see fig. 182). This tends to preserve the uniformity

of the letters: and gives a fine constructive effect,

as, for example, in the letter N.

General Remarks.—The semi-formal nature of

such a MS. would seem to permit of a good quill—

not necessarily sharp—being used with the utmost

freedom and all reasonable personal sleight of hand;

of soft tinted inks—such as browns and brown-reds ;

of an ии-ruled page (a pattern page ruled dark, being

laid under the writing pap er, will, by showing through,

keep the writing sufficiently straight), and of a mini¬

mum of precision in the arrangement of the text.

And in this freedom and informality lie the reasons

for and against the use of such a hand. There is a

danger of its becoming more informal and degenera¬

ting because it lacks the effect of the true pen in

preserving form.1 But, on the other hand, it com¬

bines great rapidity and freedom with beauty and

legibility : few printed books could compete in charm

with this old “catalogue,” which took the scribe

but little longer to write than we might take in

scribbling it.

Many uses for such a hand will suggest them¬

selves. Semi-formal documents which require to

1 Practising a more formal hand as a corrective would prevent

this.

286

be neatly written out, and Boob and Records of

which only one or two copies are required, and

even Books which are worthy to be—but never

are—printed, might, at a comparatively low cost,

be preserved in this legible and beautiful form.

It suggests possibilities for an improvement in the

ordinary present-day handwriting—a thing much to

be desired, and one of the most practical benefits

of the study of calligraphy. The practical scribe,

at any rate, will prove the advantages of being a

good all-round penman.

OF FORMAL WRITING GENERALLY

On Copying a Hand.—Our intentions being right

(viz. to make our work essentially readable) and our

actions being expedient (viz. to select and copy the

simple forms which have remained essentially the

same, leaving the complex forms which have passed

out of use—see pp. 161-2), we need not vex our¬

selves with the question of “lawfulness.”1

Where beautiful character is the natural product

of a tool, any person may at any time give such

character to a useful form, and as at this time a

properly cut and handled pen will produce letters

resembling those of the early MSS., we may take

as models such early, simple реп-forms as have

remained essentially the same,2 and copy them as

closely as we can while keeping them exact and

formal.

Finally, personal quality is essential to perfect

* The Law fulfils itself: that which we must not copy is that

which we cannot copy.

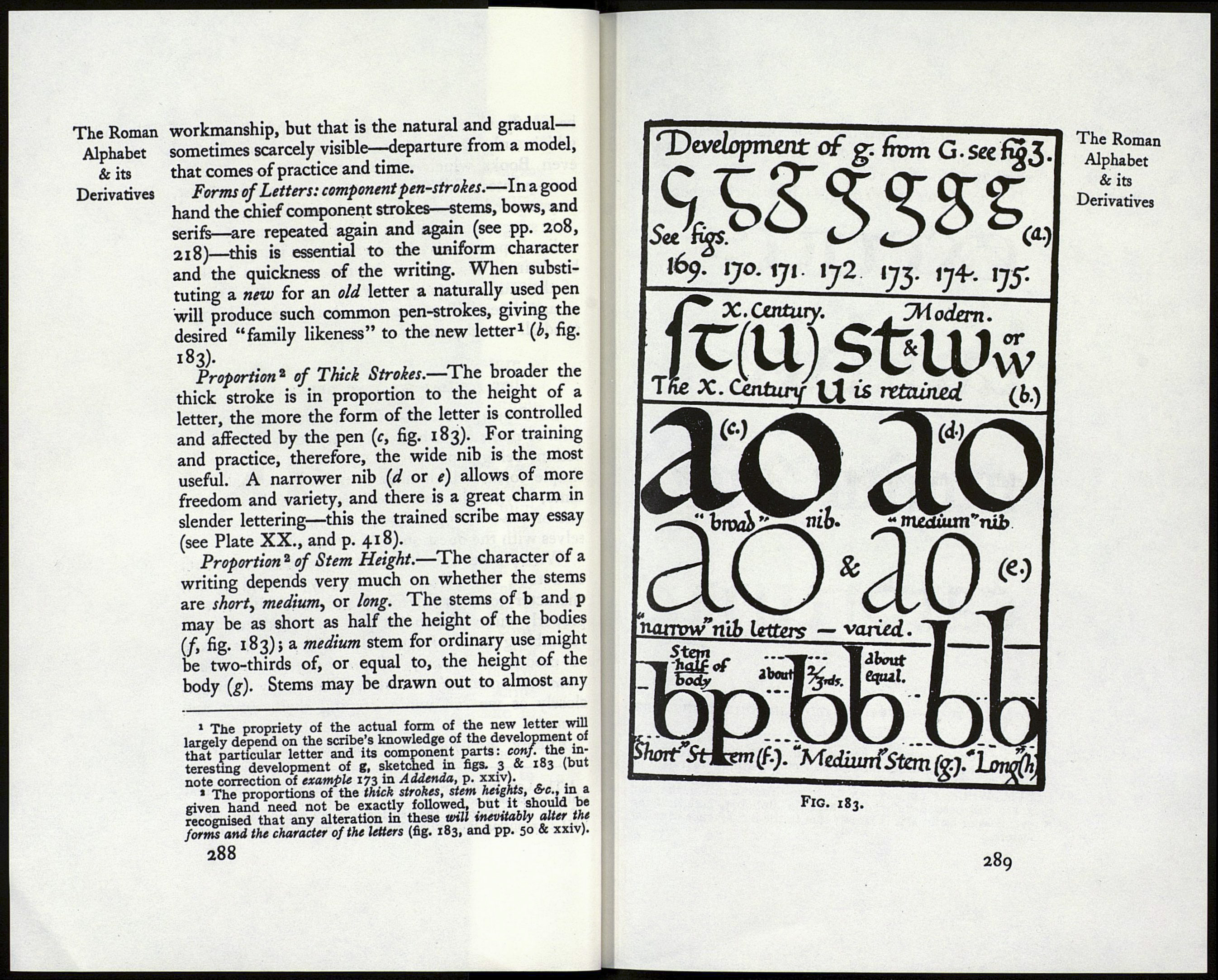

* E.g. the letters in the tenth-century English hand—Plate

VIII. : excepting the archaic long f and round Z V>, fig. 183).

287

The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives