The Roman right, and very freely written (commonly with a

Alphabet “ slanted pen"). The serifs generally consist of slight

& its natural terminal hooks, &c.—though in p and q a

Derivatives finishing stroke is sometimes added. Ascending and

descending strokes (in b, d, f h, b, I, g, j, p, q, y)

are commonly rather long, and often end in curves,

sometimes in flourishes (fig. 177).

иш I uu w

§uiy>k -smj'and Jbiuishedjtalics

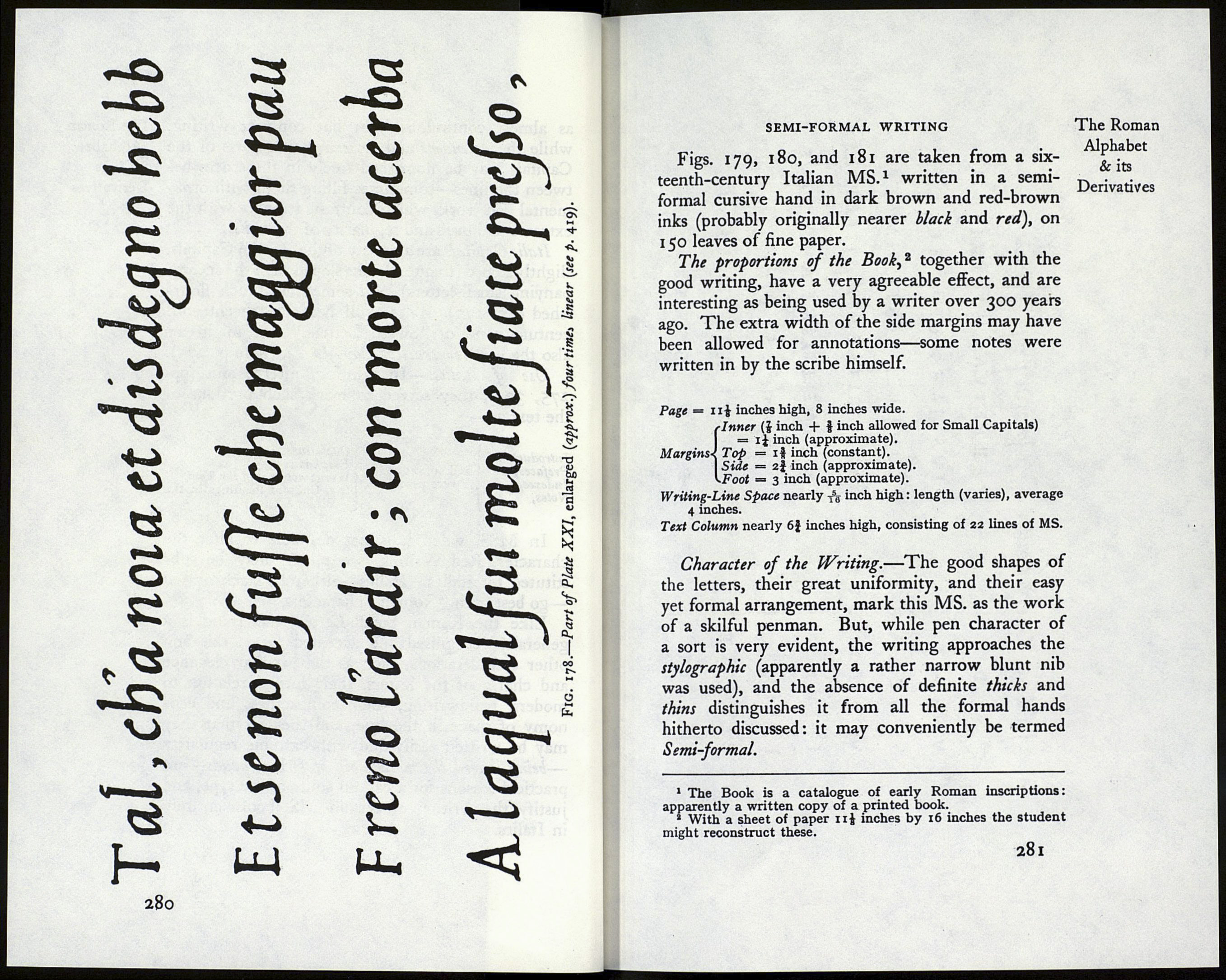

ЬЩ ЖЪѣ Fig. 177. The lines of writing are generally widely spaced Л as almost continuous light but compact writing, Italic Capitals are a variety of the Roman Capitals, Use of Italics.—In printing, after Aldus (pp. Introductions, Prefaces, Indexes, Notes, and subsequently Quotations, Emphasising, Words not part of the Text, In MSS. when it is not desirable to alter the Like the Roman Small-Letter, the Italic is a 279 The Roman

—allowing for the long stems: the bodies of the

letters being narrow are generally rather closely

packed, and frequently the lines of writing appear

278

while the ascenders and descenders and parts of the

Capitals may be flourished freely in the spaces be¬

tween the lines—sometimes filling them with orna¬

mental pen work, which contrasts strongly with the

extreme plainness and regularity of the bodies.

slightly sloped (frequently less sloped than the accom¬

panying small-letters), and sometimes much flour¬

ished (fig. 177). These still bear the seventeenth

century name of “Swash Letters.” We might try

also the early contrast of Caps & I.e. (note p. 275).

275, 337), they served to mark such portions of

the text as—

were used for

(e.g. Chapter headings in the

Bible, &c.).

character, Red Writing (see p. 96) may be sub¬

stituted for italics. Italics—either in black or red

—go best with “Roman” characters.

generally recognised and accepted form: this and

other considerations, such as the peculiar elegance

and charm of the letters, their formal relation to

modern handwriting, their compactness and eco¬

nomy of space in the line, and the fact that they

may be written easily and with extreme regularity

—being indeed the most rapid of formal hands—are

practical reasons for a careful study of the type, and

justify the writing of certain MS. books entirely

in Italics.

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives