The Roman lies, I think, in their relation to the Roman Small-

Alphabet Letter (pp. 380-1 '& 415-20), and their great

& its possibilities of development into modern formal

Derivatives hands approaching the “Roman” type.

ROMAN SMALL-LETTERS

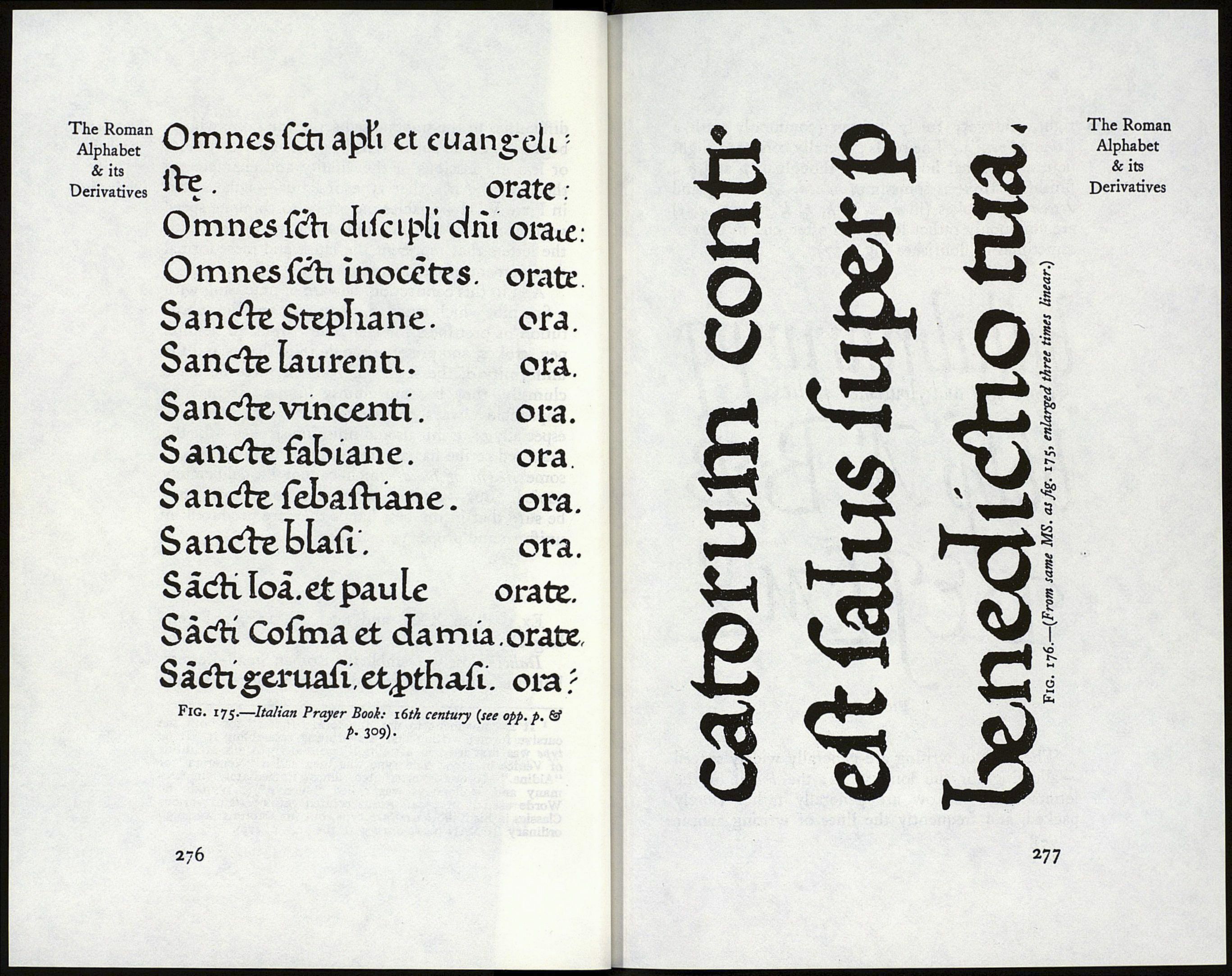

Ex.: (Italian) Plates XIX, XX (15th century);

figs. 175, 176 (16th century) : figs. 147, 148 (modern

MS.). .

The Roman Small-Letter is the universally recog¬

nised type in which the majority of books and papers

are printed. Its form has been in use for over 400

years (without essential alteration) and as far as we

are concerned it may be regarded as permanent.

And it is the object of the scribe or letter-maker

gradually to attain a fine, personal, formal hand,

assimilating to the Roman Small-Letter; a hand

against the familiar and present form of which no

allegations of unreadableness can be raised, and a

hand having a beauty and character now absent or

««familiar. The related Italic will be mastered for

formal MS. work (p. 279), and the ordinary hand¬

writing improved (p. 287). These three hands point

the advance of the practical, modern scribe.

The Roman Small-Letter is essentially a pen form

(and preferably a “slanted-pen” form; p. 269), and

we would do well to follow its natural development

from the Roman Capital—through Round Letters and

Slanted-Pen forms—so that we may arrive at a truly

developed and characteristic type, suitable for any

formal manuscript work and full of suggestions for

printers and letter-craftsmen generally.

A finished form, such as that in Plate XX—

or even that of fig. 175—would present many

274

difficulties to the unpractised scribe, and one who so

began would be apt to remain a mere copyist, more

or less unconscious of the vitality and character of

the letter. An earlier type of letter—such as that

in Plate VIII—enables the scribe to combine speed

with accuracy, and fits him at length to deal with

the letters that represent the latest and most formal

development of penmanship.

And in this connection, beware of practising with

a fine nib, which tends to inaccuracy and the substi¬

tution of prettiness for character. Stick to definite

pen strokes, and preserve the definite shapes and the

uniformity of the serifs (p. 288): if these be made

clumsily, they become clumsy lumps. It may be

impossible always to ascertain the exact forms—

especially of terminals and finishing strokes—for the

practised scribe has attained a great uniformity and

some sleight of hand which cannot be deliberately

copied. But—whatever the exact forms—we may

be sure that in the best hands they are produced by

uniform and proper pen strokes.

ITALICS

Ex.: Plate XXI, and figs. 94, 177, 178 (en¬

larged).

Italics1 closely resemble the Roman Small-Letters,

but are slightly narrowed, slightly sloped to the

1 It is convenient to use the term “Italics” for both the

cursive formal writing and the printing resembling it. Italic

type was first used in a “Virgil” printed by Aldus Manutius

of Venice in 1500. The type was then called "Venetian or

“Aldine.” It was counterfeited almost immediately (in Ger¬

many and Holland it was called “cursive”); Wynkin de

Worde used it in 1524. Aldus printed entire texts of various

Classics in his italic lower-case type, but his Capitals are small

ordinary ROMAN (in contrast with the I.e.—p. 279).

275

The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives