The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives

The main types are the “round” Uncial and

Half-Uncial, commonly written with an approxi¬

mately “straight pen."1 They are generally treated

as fine writing (p. 226), and written between ruled*

lines: this has a marked effect in preserving their

roundness (see p. 376).

They are very useful as copy-book hands (see p. 36),

for though the smooth gradation of their curves,

their thin strokes, and their general elegance unfit

them for many practical purposes, yet their essential

roundness, uprightness, and formality afford the finest

training to the penman, and prevent him from falling

into an angular, slanting, or lax hand. Their very

great beauty, moreover, makes them well worth

practising, and even justifies their use (in a modern¬

ised form) for special MSS., for the more romantic

books — such as poetry and “fairy tales”—and

generally where speed in writing or reading is not

essential.

With an eye trained and a hand disciplined by

the practice of an Irish or English Half-Uncial, or

a modified type, such as is given in fig. 50, the

penman may easily acquire some of the more

practical later “slanted-pen” types.

“slanted-pen” small-letters

Typical Examples:—

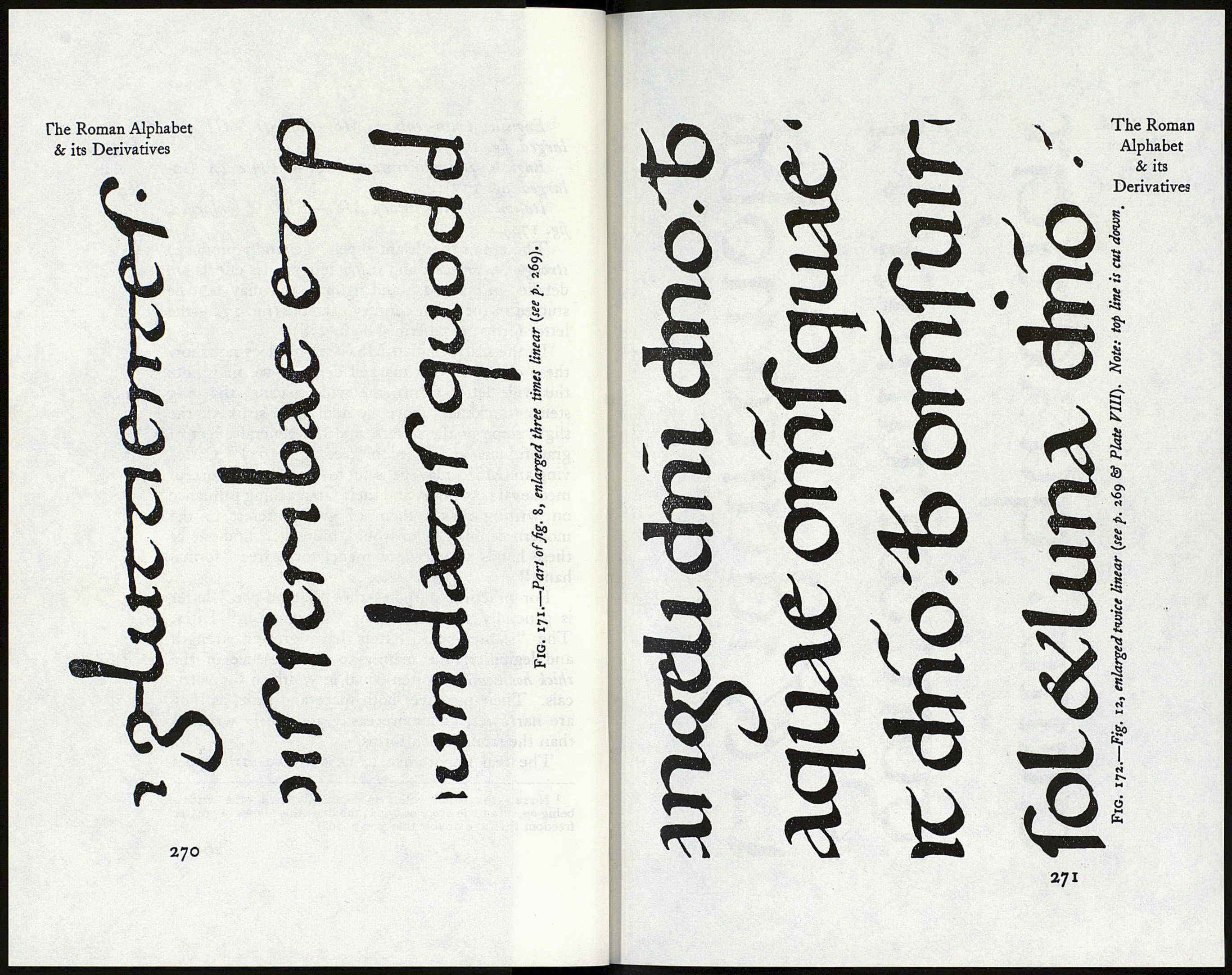

Carlovingian ninth-century MS. — Fig. 8 (en¬

larged, fig. 171):

1 The writing in fig. 170 shows a slightly slanted pen. To

make quite horizontal thins is difficult, and was probably never

done, but it is worth attempting them nearly horizontal for the

sake of training the hand.

268

English tenth-century MS. — Plate Fill (en¬

larged, fig. 172):

English eleventh-century MS. — Plate IX (en¬

larged, fig. 173):

Italian twelfth-century MS.—Plate X (enlarged,

fig. 174).

The use of the “slanted pen” generally produced

stronger, narrower, and stiffer letters. Its effects are

detailed in pp. 9-13, and fig. 11, and may best be

studied in the tenth-century example (fig. 172—the

letter forms are described on p. 378).

In the Carlovingian MS.—which does not show

these effects in any marked degree—we may note

the wide letter forms, the wide spacing, the long

stems (thickened above by additional strokes), the

slight slope of the letters, and the general effect of

gracefulness and freedom (see fig. 171). Carlo¬

vingian MSS. may be said to represent a sort of

mediaeval copy-books, and their far-reaching influence

on writing makes them of great interest to the

modern penman, who would, moreover, find one of

these hands an excellent model for a free “formal

hand.”

For practical purposes the “slanted-pen” letter

is generally superior to the “straight-pen” letter.

The “slanted-pen” letters have greater strength

and legibility, due mainly to the presence of the

thick horizontals—often equal in width to the verti¬

cals. Their use saves both space and time, as they

are narrower, and more easily and freely written1

than the straight-pen forms.

The real importance to us of these early types

1 Note.—S*»igii-line ruling is commonly used—the writing

being on, or a little above or below, the line : this allows of greater

freedom than the double line (see p. 268).

269

The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives