The Roman make the proper strokes automatically : then he may

Alphabet begin to master and control the pen, making it con-

& its form to his hand and so produce Letters which have

Derivatives every possible virtue of penmanship and are as much

his own as his common handwriting.

Most of the letters in a good alphabet have

specially interesting or characteristic parts (p. 214),

or they exhibit some general principles in letter

making, which are worth noting, with a view to

making good letters, and in order to understand

better the manner in which the tool—whether pen,

chisel, or brush—should be used.

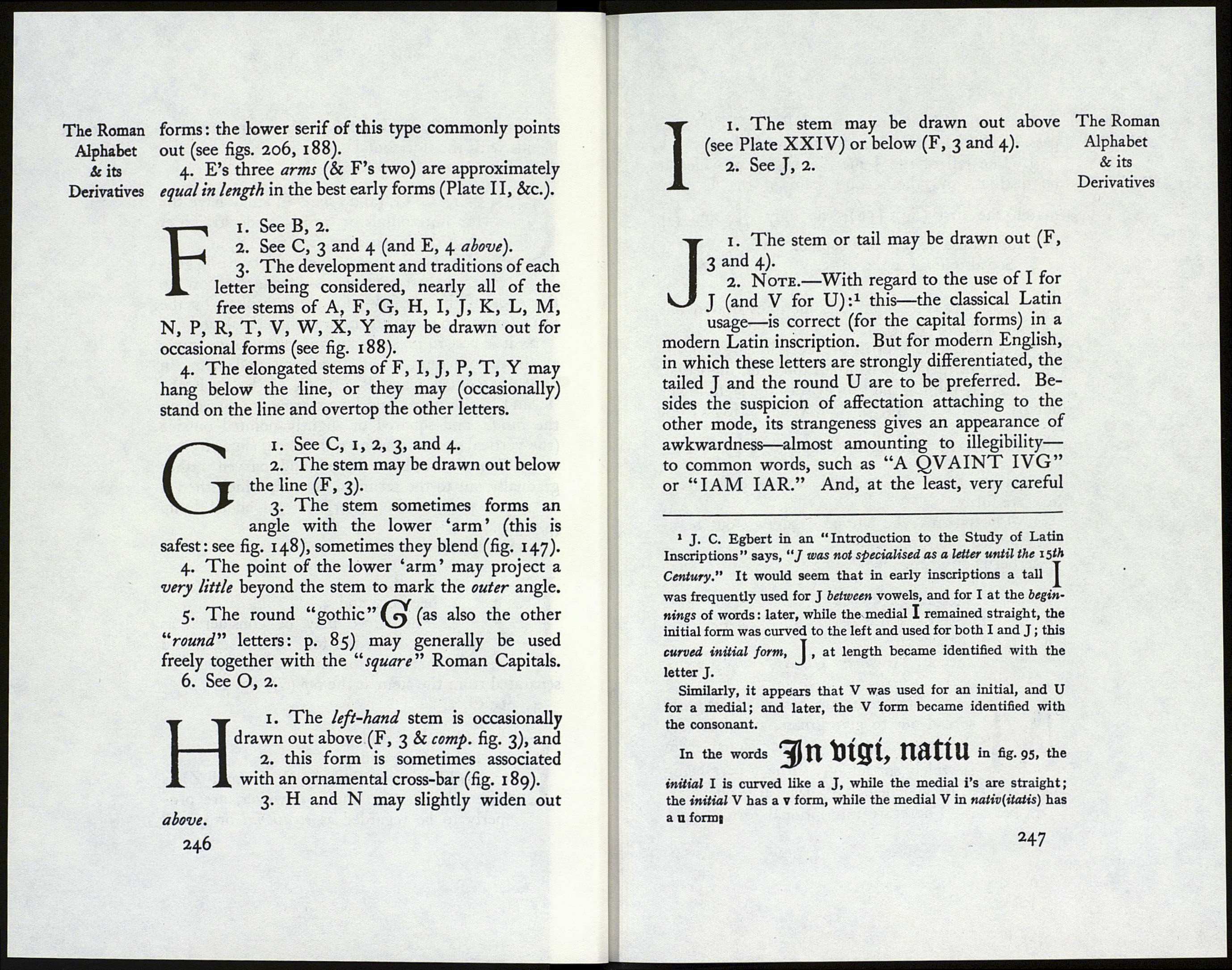

The characterisation of the Roman Capital Form.

Note.—The large types below are indices—not models.

A I. A pointed form of A, M, and N (see

Plate II) may be suitable for inscriptions

in stone, &c., but in pen work the top is

preferably hooked (fig. 167), beaked (fig.

147), or broken (fig. 158), or specially

marked in some way, as this part (both in Capital

A and small a) has generally been (fig. 189).

2. The oblique strokes in А, К, M, N, R, V,

W, X, Y, whether thick or thin, are naturally

finished with a short point inside the letter and a

long, sharp point, or beak, outside (see serifs of oblique

strokes, p. 253).

3. The thin stem may be drawn out below for

an occasional form (see F, 3).

1. B, D, R, and P are generally best

mad & round-shouldered (fig. 162 & Addenda,

p. xxiv).

2. B, D, E, F, P, R (and T) have gen¬

erally an angle between the stem and the

top horizontal, while

В

244

3. below in B, D, E (and L) the stem curves or

blends with the horizontal.

4. See O, 2.

С i. C, G, (and round Q ) may have the

top horizontals or ‘arms’ made straighter

than the lower arms (see fig. 187).

2. C, G, S, &c. ; the inside curve is gen¬

erally best continuous—from the ‘bow’ to

the ends of the ‘arms’—not being broken by the

serifs (except in special forms and materials), and

3. it is best to preserve an unbroken .inside curve

at the termination of all free arms and stems in

built-up Roman Capitals. In C, G, S, E, F, L,

T, and Z the upper and lower arms are curved on

the inside, and squared or slightly pointed outside

(the vertical stems curve on either side) (fig. 163).

4. ‘Arms’ are best shaped and curved rather

gradually out to the terminal or serif, which then is

an actual part of the letter, not an added lump

(P- 253)-

5. See O, 2.

Di. See В, i.

2. See B, 2 and 3.

3. The curve may be considered as

springing from the foot of the stem, and

may therefore for an occasional form be

separated from the stem at the top (©, fig. 177).

4. See O, 2.

1. See B, 2 and 3.

2. See C, 3 and 4.

3. The lower limb in E, L (and Z) is

often drawn out: these, however, are pro¬

perly to be regarded as occasional or special

245

E

The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives