The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives

its actual position above the centre.1 And further,

by a reasonable enlargement of the lower part, these

letters acquire a greater appearance of stability.

It would be well, I think, for the letter-craftsman

to begin by making such divisions at the apparent

centre {i.e. very slightly above mid-height; see

E, F, X, Plate II), so keeping most nearly to the

essential forms (see p. 239). Later he might con¬

sider the question of stability (see B, Plate II).

The exaggerated raising (or lowering) of the divi¬

sion associated with “Art Lettering” is illegible

and ridiculous.

A The lower part is essentially bigger, and

the cross-bar is not raised, as that would

make the top part disproportionately small.

F usually follows E, but being asymmetrical and

open below it may, if desired, be made with

the bar at—or even slightly below—the actual

centre.

RIn early forms the bow was frequently

rather large (see Plate II), but it is safer

to make the tail—the characteristic part—more

pronounced (see Plates III, XXIV).

PThe characteristic part of P is the bow,

which may therefore be a little larger than

the bow of R (see Plate III).

Sin the best types of this letter the upper

and lower parts are approximately equal ;

there is a tendency slightly to enlarge the lower

1 It is interesting to note in this connection that the eye

seems to prefer looking upon the tops of things, and in reading,

is accustomed to run along the tops of the letters—not down

one stroke and up the next. This may suggest a further reason

for smaller upper parts, viz. the concentration of as much of the

letter as possible in the upper half.

238

part. (In Uncial and early round-hands the top part

was larger: see Plates IV to VII.)

Y varies: the upper part may be less than that

of X, or somewhat larger.

ESSENTIAL OR STRUCTURAL FORMS

The essential or structural forms (see p. 204) are

the simplest forms which preserve the characteristic

structure, distinctiveness, and proportions of each indi¬

vidual letter.

The letter-craftsman must have a clear idea of

the skeletons of his letters. While in every case the

precise form which commends itself to him is matter

for his individual choice, it is suggested in the

following discussion of a typical form—the Roman

В—that the rationale of his selection (whether

conscious or unconscious) is in brief to determine

what is absolutely essential to a formi and then how

far this may be amplified in the direction of the practi¬

cally essential.

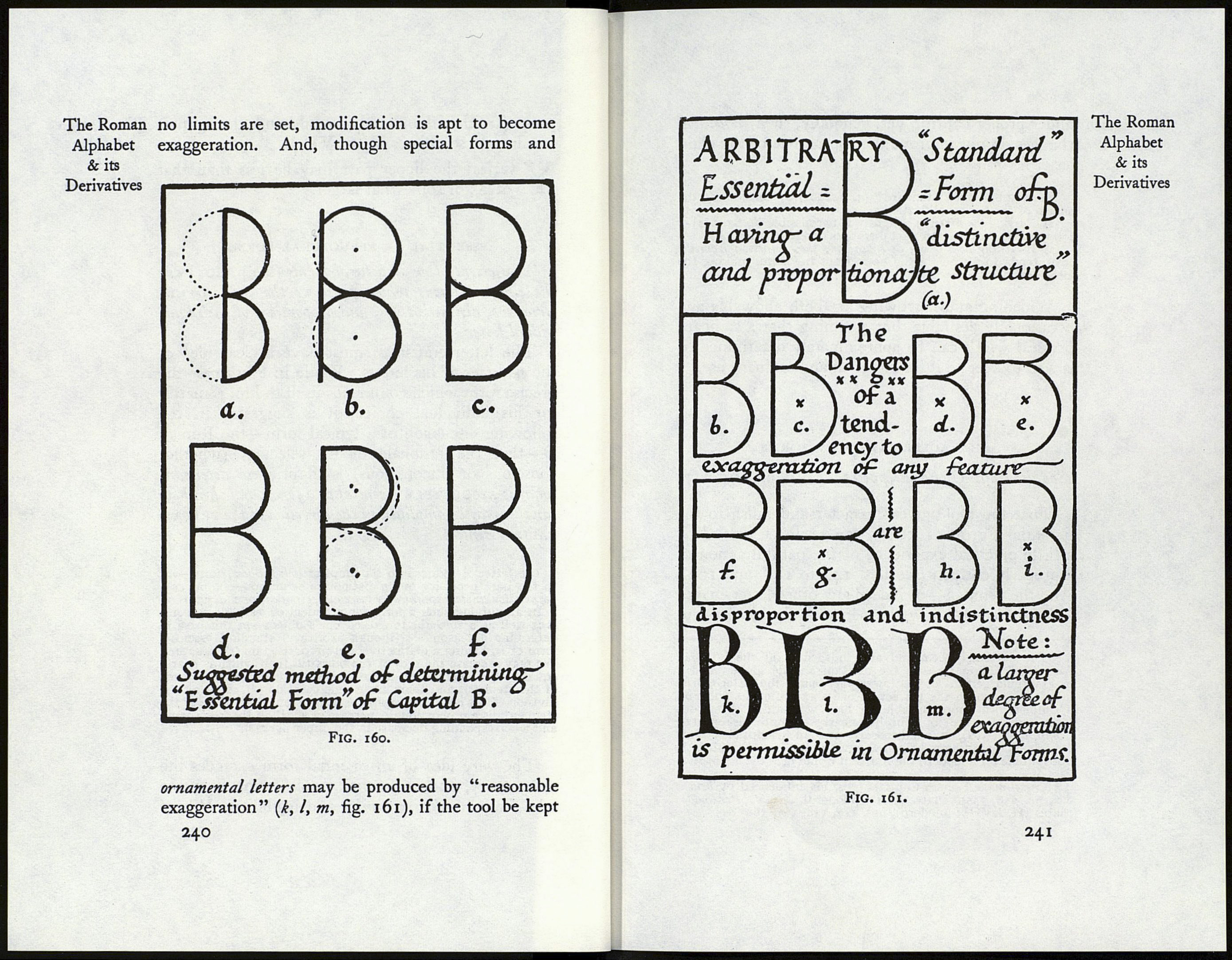

The letter В reduced to its simplest (curved-bow) form—i.e.

to the bare necessity of its distinctive structure—comprises a

perpendicular stem spanned by two equal, circular bows (a, fig. 160).

In amplifying such a form for practical or aesthetic reasons,

it is well as a rule not to exceed one’s object—in this case to

determine a reasonable (though arbitrary) standard essential

form of B, having a distinctive and proportionate (/) structuré.

We may increase the arcs of the bows till their width is nearly

equal to their height (b), make their outer ends meet the ends

of the stem (c), and their inner ends coincide (d). Raising the

division till its apparent position is at or about the middle of the

stem entails a proportionate increase of width in the lower part,

and a corresponding decrease in the upper part («).

The very idea of an essential form excludes the

««necessary, and its further amplification is apt to

take from its distinctiveness and legibility. Where

239

The Roman

Alphabet

& its

Derivatives