Good is natural and obvious, and no fault of the scribe’s.

Lettering— Such an arrangement, or rather, straightforward

Some writing, of poetry is often the best by virtue of its

Methods of freedom and simplicity (see p. 335).

Construction In many cases, however, a more formal and

& Arrange- finished treatment of an irregular line text is to be

ment preferred (especially in inscriptions on stone, metal,

&c.), and the most natural arrangement is then an

approximately symmetrical one, inclining to “Fine

Writing” in treatment. This is easily obtained in

inscriptions which are previously set-out, but a good

plan—certainly the best for MSS.—is to sort the

lines of the text into longs and shorts (and sometimes

medium lines), and to set-in or indent the short lines

two, three, or more letters. The indentations on

the left balance the accidental irregularities on the

right (fig. 154, and Plate IV), and given an appear¬

ance of symmetry to the page (see Phrasing, p. 348).

Either mode of spacing (close or wide) may be

carried to an unwise or ridiculous extreme. “Lead¬

ing” the lines of type was much in vogue a hundred

years ago, in what was then regarded as “high-

class” printing. Too often the wide-spaced line

and “grand” manner of the eighteenth-century

printer was pretentious rather than effective: this

was partly due to the degraded type which he used,

but form, arrangement, and expression all tended to

be artificial. Of late years a rich, closely massed

page has again become fashionable. Doubtless there

has been a reaction in this from the eighteenth

century to an earlier and better manner, but the

effect is sometimes overdone, and the real ease and

comfort of the reader has been sacrificed to his rather

imaginary aestheticism.

By attaching supreme importance to readableness,

228

the letter-craftsman gains at least a rational basis for

his work, and is saved from the snares which lurk

in all, even in the best, modes and fashions.

EVEN SPACING

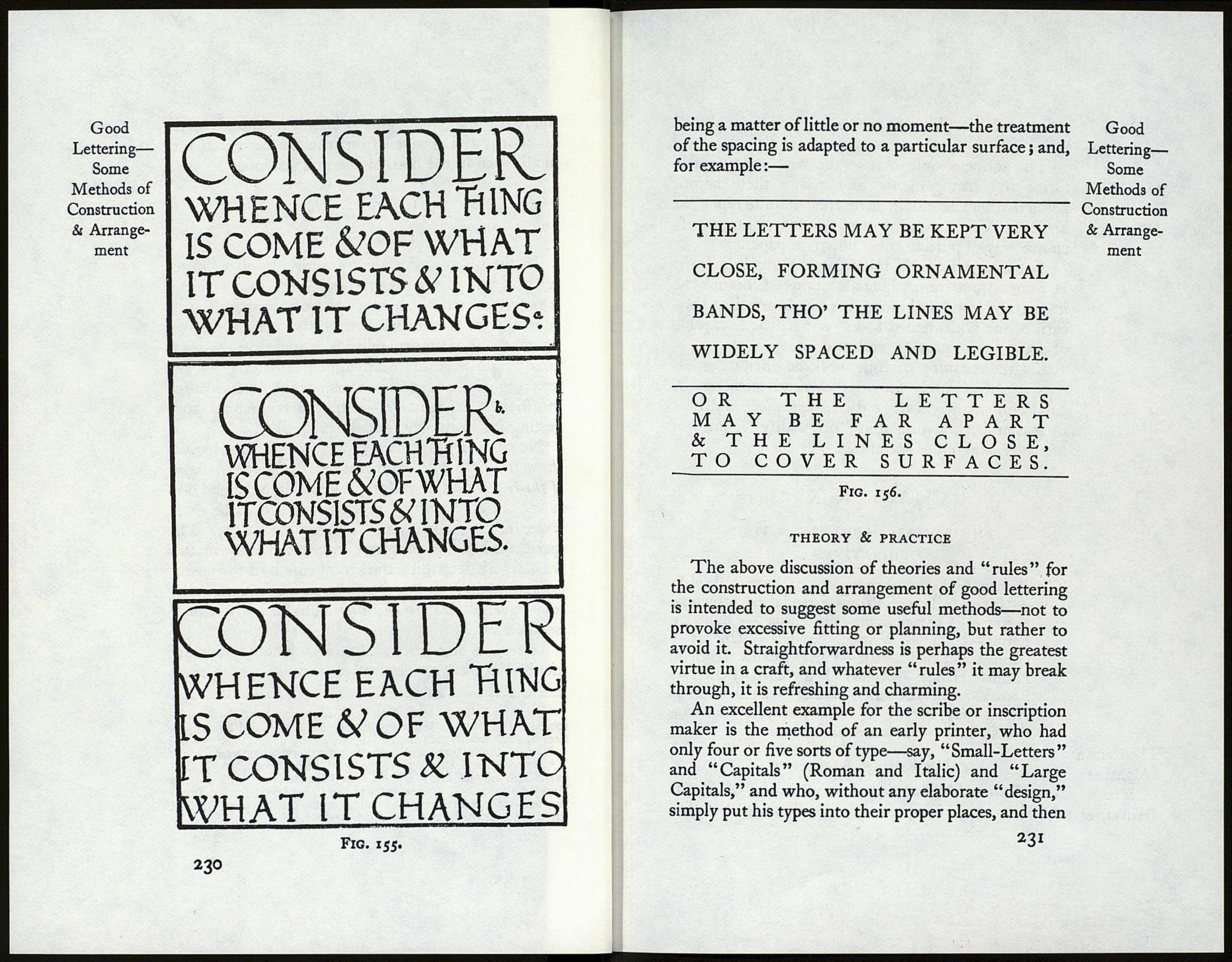

In the spacing of a given inscription on a limited

surface, where a comparatively large size of letter

is required, what little space there is to spare should

generally be distributed evenly and consistently (a,

fig. 155). Lavish expenditure of space on the mar¬

gins would necessitate an undue crowding1 of the

lettering (è), and wide interspacing2 would allow

insufficient margins (c)—either arrangement sug¬

gesting inconsistency (but see p. 316).

Note.—A given margin looks larger the heavier

the mass of the text,3 and smaller the lighter the mass

of the text. And, therefore, if lettering be spread out,

as in “Fine Writing,” the margins should be extra

wide to have their true comparative value. The

space available for a given inscription may in this

way largely determine the arrangement of the letter¬

ing, comparatively small and large spaces suggesting

respectively “Massed Writing” and “Fine Writing”

(see p. 226).

In certain decorative inscriptions, where letters are

merely treated as decorative forms—readableness

1 In (6) fig. 155, the letters have been unintentionally nar¬

rowed. The natural tendency to do this forms another objec¬

tion to such undue crowding.

* In (c) the letters have been unintentionally widened.

* Experiment.—Cut out a piece of dark brown paper the

exact size of the body of the text in an entire page of this

Handbook, viz. 5-fV inches by 3 inches, and lay it on the text:

the tone of the brown paper being much darker than that of

the print makes the margins appear wider.

229

Good

Lettering—

Some

Methods of

Construction

& Arrange¬

ment