Good “тн—rough,” or “neigh-bour,” should not be

Lettering— allowed. Among other ways of dealing with small

Some spaces, without breaking words, are the following :—

Methods of Ending with Smaller Letters.—The scribe is al-

Construction ways at liberty to compress his writing slightly,

Sc Arrange- provided he does not spoil its readableness or beauty,

ment Occasionally, without harming either of these, a

marked difference in size of letter may be allowed ;

one or more words, or a part of one, or a single letter,

being made smaller (a, b, fig. 153 ; see also Plate V).

Monogrammatic Forms, &c.—In any kind 6f letter¬

ing, but more particularly in the case of capitals,

where the given space is insufficient for the given

capitals, monogrammatic forms resembling the ordi¬

nary diphthong Æ may be used; or the stem of

one letter may be drawn out, above or below, and

formed into another (c, fig. 153).

Linking.—Letters which are large enough may

be linked or looped together, or one letter may be set

inside another, or free-stem letters may be drawn up

above the line (d, fig. 153, but see p. xxiv).

Tying up.—One or more words at the end of a

line of writing—particularly in poetry (see p. 61)—

may be “tied up,” i.e. be written above or below the

line, with a pen stroke to connect them to it (fig. 67).

Care must be taken that none of these methods

lead to confusion in the reading. Their “Quaint¬

ness”—as it is sometimes called—is only pleasing

when their contrivance is obviously made necessary.

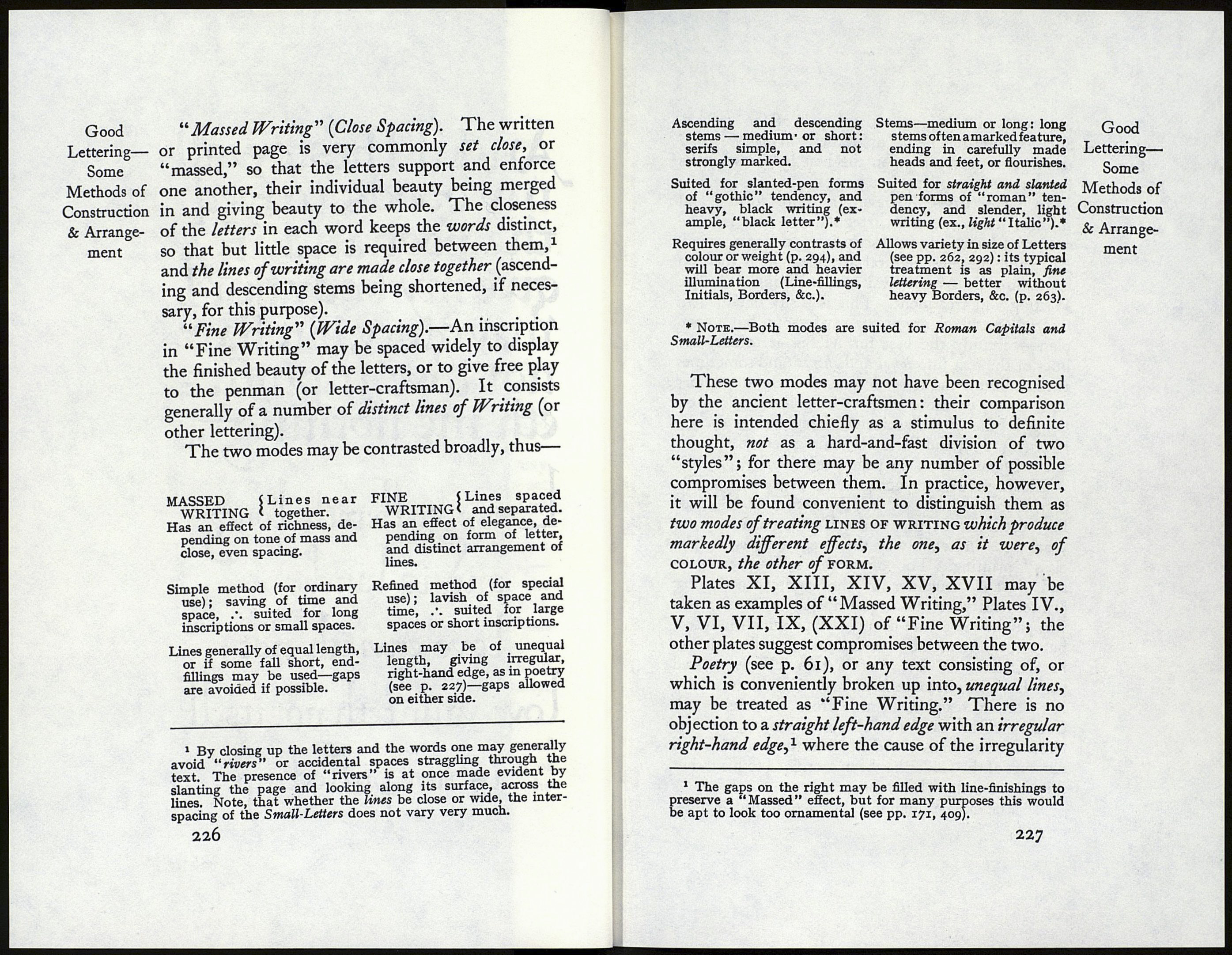

“massed writing” & “fine writing”

We may distinguish two characteristic modes of

treating an inscription, in which the treatment of

the letter is bound up with the treatment of the

spacing (fig. 154).

224

And if I bestowal!

my opods to h?cti

the poor, and if I

owe my body tlut I

may otory, but Ime

not love/it pro

crii me потігиг^

Ljfove suiicretk lonj'',

art^ is l

love vauntedi not itseU"

jnmm up,

is not

Fig. 154.

225

Good

Lettering—

Some

Methods of

Construction

& Arrange¬

ment