Good This summary, while not presuming to define the

Lettering— Virtues, or achieve Beauty by a formula, does indicate

Some some guiding principles for the letter-maker, and

Methods of does suggest a definite meaning which may be

Construction given to the terms “Right Form,” “Right Arrange-

& Arrange- ment,” and “Right Expression” in a particular

ment craft.

It is true that “Readableness” and “Character”

are comprised in Beauty, in the widest sense; but

it is useful here to distinguish them: Readableness

as the only sound basis for a practical theory of

lettering, and Character as the product of a particular

hand & tool at work in a particular craft.

The above table, therefore, may be used as a test

of the qualities of any piece of lettering—whether

Manuscript, Printing, or Engraving—provided that

the significations of those qualities on which “Char¬

acter” depends be modified and adapted to each

particular instance. It is however a test for general

qualities only—such as may help us in choosing a

model: for as to its particular virtue each work

stands alone—judged by its merits—in spite of all

rules.

SIMPLICITY

{As having no unnecessary parts)

Essential Forms and their Characterisation.—The

“Essential Forms” may be defined briefly as the

necessary parts (see p. 239). They constitute the

skeleton or structural plan of an alphabet; and One

of the finest things the letter-craftsman can do, is to

make the Essential Forms of letters beautiful in them¬

selves, giving them the character and finish which come

naturally from a rightly handled tool.

204

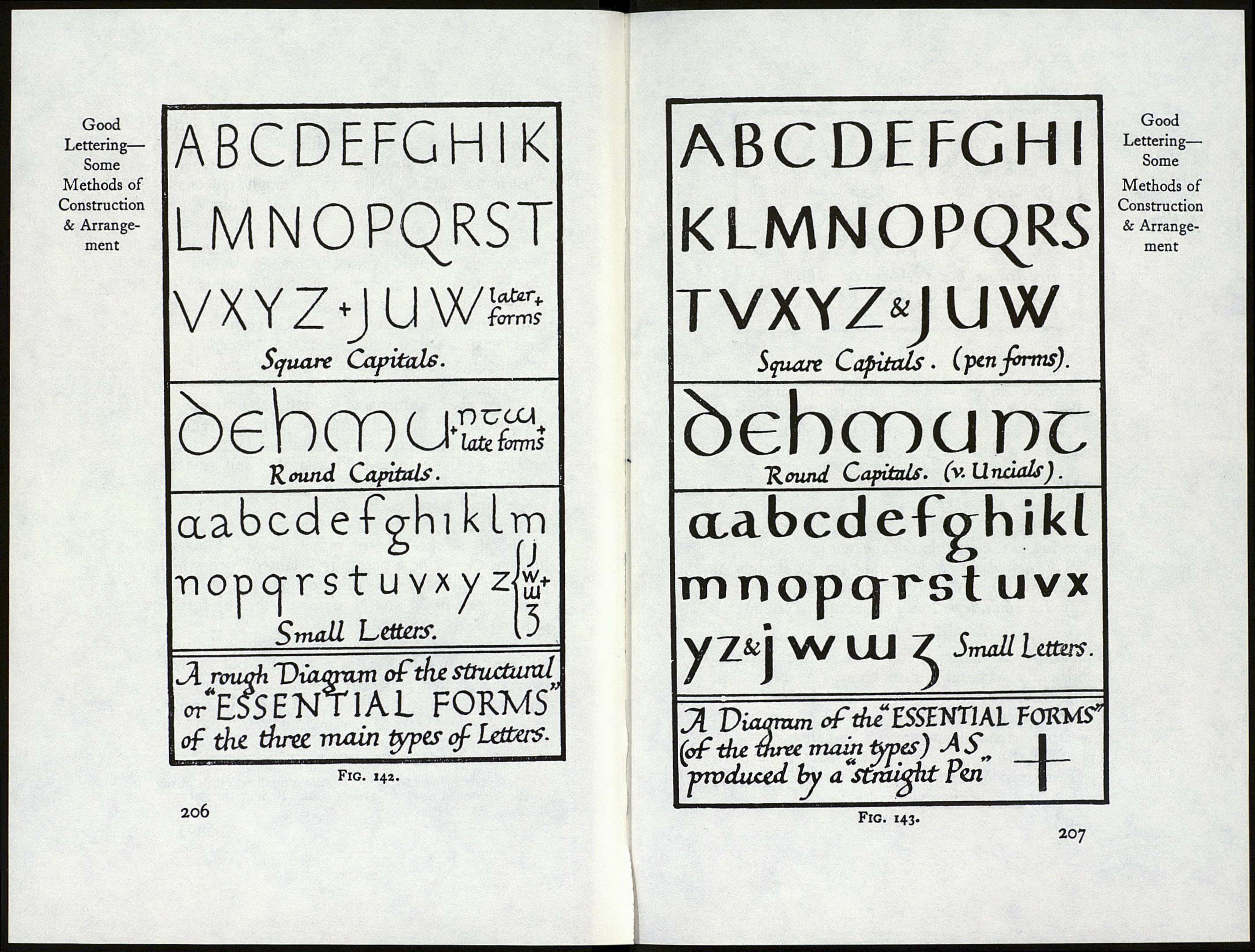

If we take the “Roman” types—the letters

with which we are most familiar—and draw them

in single pencil strokes (as a child does when it

“learns its letters”), we get a rough representa¬

tion of their Essential Forms (see diagram, fig.

142).

Such letters might be scratched with a point in

wax or clay, and if so used in practice would give

rise to fresh and characteristic developments,1 but

if we take a “square cut” pen which will give a

thin horizontal stroke and a thick vertical stroke

(figs. 10 and 40), it will give us the “straight-pen,"

or simple written, essential forms of these letters

(% 143)-

These essential forms of straight-pen letters when

compared with the plain line forms show a remark¬

able degree of interest, brought about by the intro¬

duction of the thin and thick strokes and gradated

curves, characteristic of pen work.

Certain letters (А, К, M, N, V, W, X, Y, and

к, V, w, X, y) in fig. 143 being composed chiefly

of oblique strokes, appear rather heavy.. They are

lightened by using a naturally “slanted” pen which

produces thin as well as thick oblique strokes. And

the verticals in M and N are made thin by further

slanting the pen (fig. 144).

To our eyes, accustomed to a traditional finish,

all these forms—in figs. 143 and 144, but particu¬

larly the slanted pen forms—look incomplete and

unfinished; and it is obvious that the thin strokes,

at least, require marked terminals or serifs.

1 In fact, our “ small-letters ” are the formalised result of the

rapidly scratched Square Capitals of the Roman era (p. 33 &

fig- 3).

205

Good

Lettering—

Some

Methods of

Construction

& Arrange¬

ment