“Design” in which in itself would form a foundation for a splendid

Illumination and complete scheme of Illumination.

SCALE & SCOPE OF DECORATION

Penmanship.—Many of the most beautiful MSS.

were made in pen-work throughout.1 And it is well

that the penman should stick to his pen as much as

is possible. Not only does it train his hand to make

pen ornaments, the forms of which are in keeping

with the writing, but it helps to keep the decoration

proportionate in every way. It is an excellent plan

for the beginner to use the writing-pen for plain

black capitals or flourishes, and to make all other

decoration with similar or slightly finer pens than

the one used for the writing.

Again, the direct use of the pen will prevent much

mischievous “sketching.” Sketching is right in its

proper place, and, where you know exactly what you

wish to do, it is useful to sketch in lightly the main

parts of a complex “design” so that each part may

receive a fair portion of the available space. But do

not spoil your MS. by experimental pencilling in

trying to find out what you want to do. Experiments

are best made roughly with a pen or brush on a piece

of paper laid on the available space in the MS., or

by colouring a piece of paper and cutting it out to

the pattern desired and laying it on. Such means are

also used to settle small doubts which may arise in

the actual illuminating—as to whether—and where

1 A most beautiful twelfth-century MS., known as the

“Golden Psalter,” has many gold (decorated) Initials, Red,

Blue, and Green (plain) Versals and Line-Finishings, every pari

being pen-made throughout the book.

184

—some form or some colour should be placed on

the page.

Filigree, Floral, & other Decoration.—The ac¬

quired skill of the penman leads very naturally to

a pen flourishing and decoration of his work, and

this again to many different types of filigree decora¬

tion more or less resembling floral growths (see figs.

125, 1265 pp. 163-8 ; Plates XI, XVII).

Now all right decoration in a sense arranges itself \

and we may compare the right action of the

“designer’s” mind to that necessary vibration or

“directive” motion which permeates the universe

and, being communicated to the elements, enables

the various particles to fall into their right places:

as when iron filings are shaken near a magnet they

arrange themselves in the natural curves of the mag¬

netic field, or as a cello bow, drawn over the edge

of a sand-sprinkled plate, gathers the sand into

beautiful “musical patterns.”

And to most natural growths, whether of plants

or ornament, this principle of self-arrangement seems

common, that they spread out evenly and occupy to the

greatest extent possible their allotted space. Branches

and leaves most naturally grow away from the stem

and from each other, and oppose elbows and points

in every direction. In this way the growth fits its

place, looking secure and at rest—while in discon¬

nected parallels, or branches following their stem,

there is often insecurity and unrest.1 (See also

Addenda, p. xxiii.)

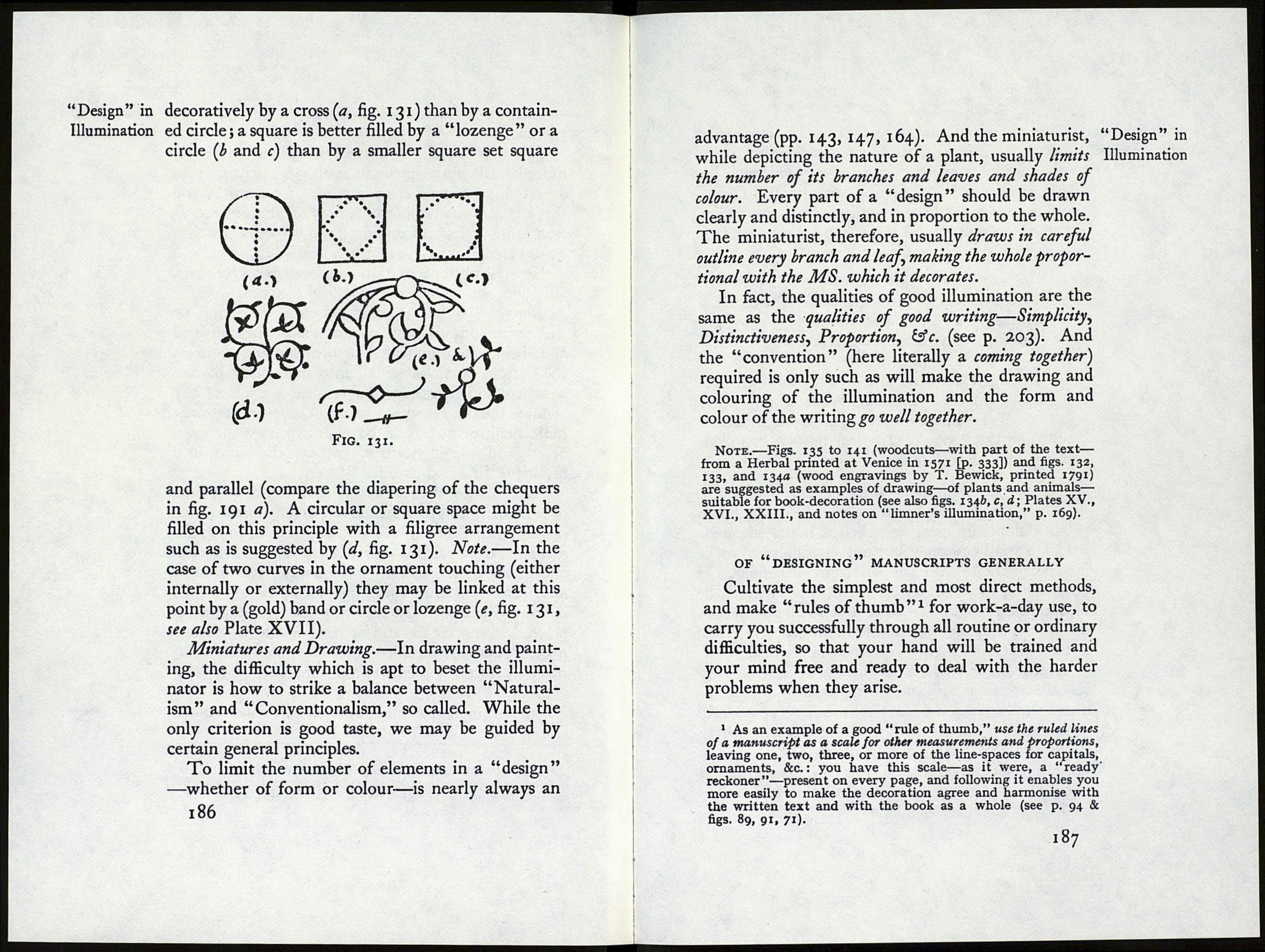

For example: a circular space is filled more

1 In a spiral the stem, following itself, may be tied by an inter¬

lacing spiral, or the turns of the spiral may be held at rest by

the interlocking of the lèaves (see G, Plate XXII).

185

“Design” in

Illumination