A Theory of and with these simple elements he builds up a pleasant

Illumination “design,” which he tools, usually in gold-leaf, upon

the cover.

The scribe can vary the forms which his pen

produces, and the colours which he gives them,

with a freedom that the set form and the method

of using the binder’s tools do not allow. But the

skilled penman will find that his pen (or, at any

rate, his penmanship) largely determines the forms of

his freest flourishes and strokes, and that the semi-

formal nature of such ornament demands a certain

simplicity and repetition of form and colour, which

do not unduly tax his skill as a craftsman.

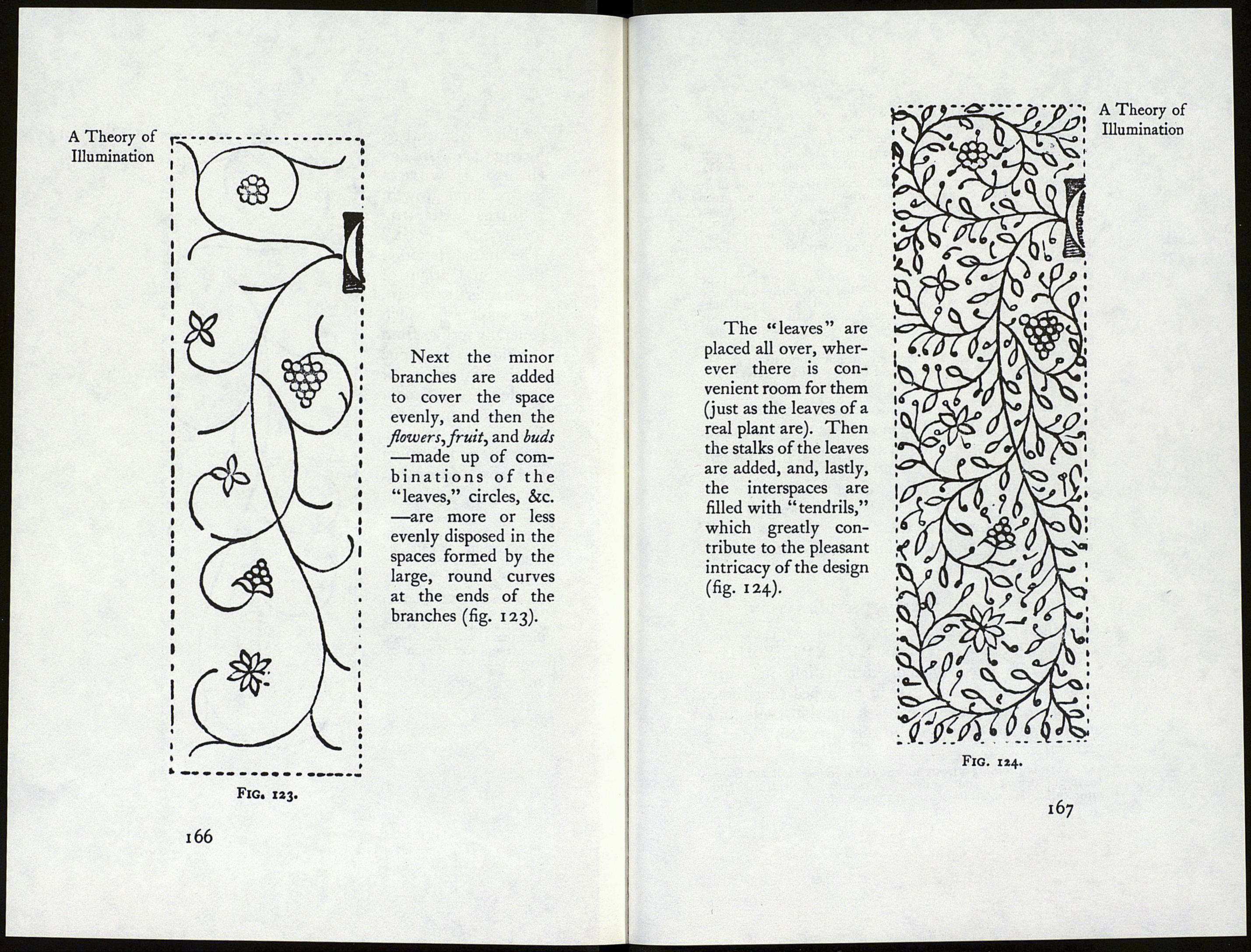

Suppose, for example, that the scribe wishes to

illuminate the border of a page of writing. He may

choose a limited number of simple, pen-made forms

for the elements of his design; say, a circle, a “leaf,”

and a “tendril,” and a few curved flourishes and

strokes (fig. 121), and with these cover the allotted

space evenly and agreeably.

164

The ornament

being treated as

though it were a

sort of floral growth,

requires a starting

point or “root.”

The initial letter is

the natural origin of

the border ornament,

the stalk of which

generally springs from

the side or from one

of the extremities of

the letter. The main

stem and branches are

first made with a

very free pen, forming

a skeleton pattern (fig.

122).

Note.—The numbers in

the diagram indicate the

order in which the strokes

were made. The main stem

(hi) sweeps over and oc¬

cupies most of the ground ;

the secondary stem (222)

occupies the remainder ;

the main branches (333,

&c.) make the occupation

secure.

■n A Theory of

í Illumination

J

Fig. 122.

165