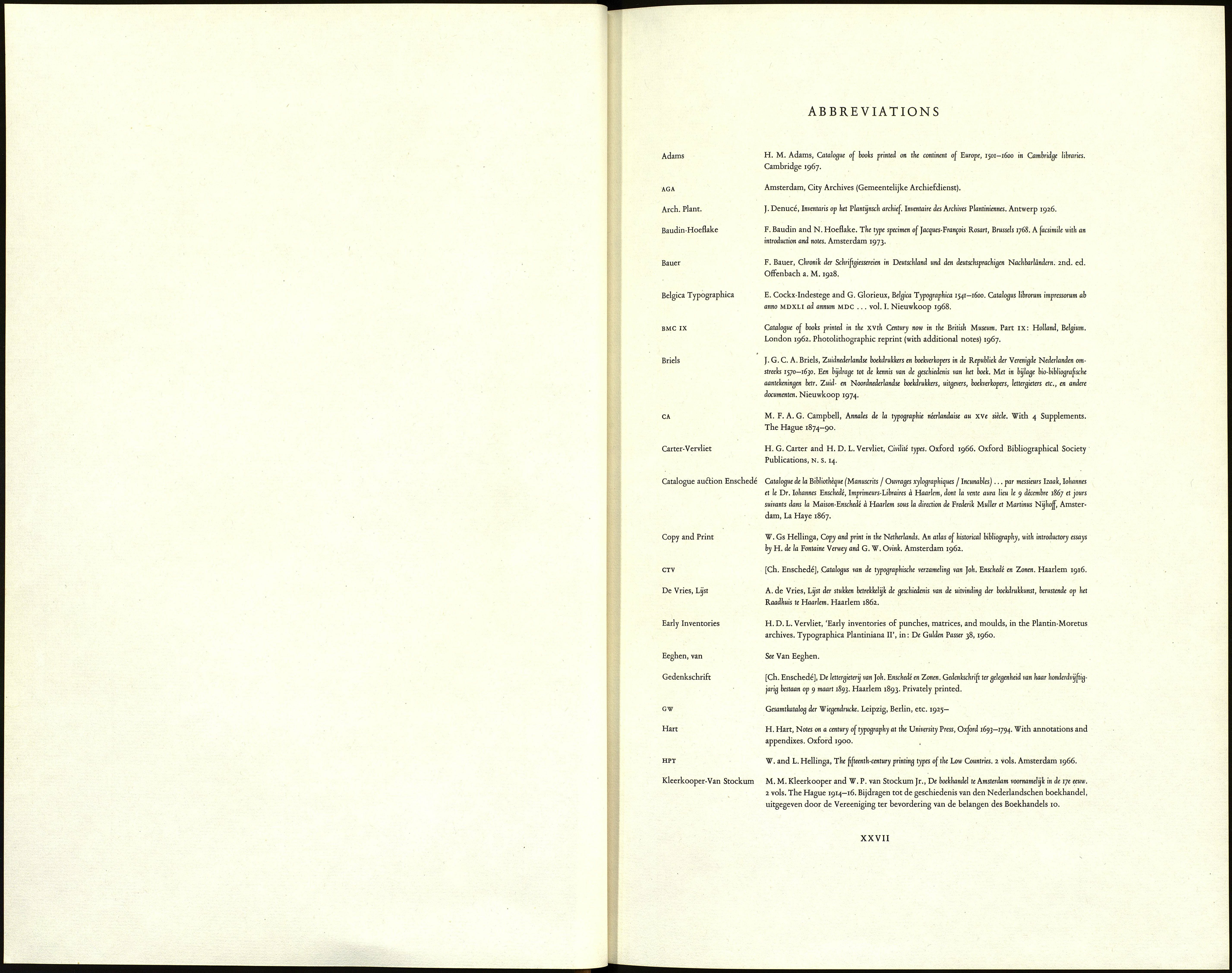

15th. Century i6tk. Century ijth. Century 18th. Century Total

Black Letter 5

6

28

39

Roman and Italic

i1

10

74

85

German vernacular

1

51

52

Greek

2

5

7

Ц

Arabic

2

3

5

Arabized Malay

1

3

4

Romanized Malay

3

3

Syriac

i2

1

Armenian

4

4

Hebrew

4

- 23

27

Rabbinical

1

10

11

Script

5

1

11

4

German Script

3

3

Hebrew Script

I

I

Shaded

I

I

Titling capitals:

Roman and Italic3

1

2

4

27

Greek

6

6

Script

2

8

10

Shaded

5

"5

Greek shaded

4

4

Script shaded

1

1

Ornamented

13

13

Woodcut initials

*5

16

31

Psalm-notes

2

5

7

Measured music

2

2

II

51 316 383

[1] The early Roman typeface described hereafter on pp. [3] Those that have no matching lower-case and are in-

29-32 is attributable to the first quarter of the i6th. century. tended for use in titles, headings, and displayed work. If used

[2] If the Syriac derives direftly from the face cut by as initials at the beginning of chapters they align with the

Granjon for Plantin, it belongs to the i6th century. second line of the text.

XXIV

INTRODUCTION

to Gutenberg. Is it not remarkable, too, that we find type imitating exactly the

handwriting of the sixteenth century?1

The study of old printing types leads quite often to interesting insights into mat¬

ters of history. An example is my discovery by examining certain types of a means

of proving that the famous Elseviers of Leyden never had a typefoundry, or even,

with unimportant exceptions, any types that were peculiar to them; it was only

after 1670 that Daniel Elsevier set up a typefoundry in Amsterdam. In the same

way I found out that the disastrous fire in Blaeu's premises in 1672 consumed only

his printing house and did not extend to his foundry. In a different department of

printing history I hit upon evidence showing that in making type for [polyphonic]

music Breitkopf and Fleischman were anticipated by Rosari. Rosari had found a

method of doing it, albeit an imperfect, one, five or six years before the other two.2

A curious faci: to end with. Typographical printing is a trade, an industry, but

also to some extent an art. It is generally considered, no doubt rightly, that the

quality of printing in a country bears a relation to the artistic development of its

people; so it is strange that the Low Countries, where in the past artistic sensi¬

bility has been so vital, have never had a style of typography of their own. Only

in the early Black Letters and [Gothic] scripts do we find national peculiarities:

Roman and Italic we seem always to have borrowed from elsewhere. The best

of our punchcutters, excepting only the Voskens, were foreigners who settled in

the Netherlands3 but cut typefaces after foreign models. There has never been

a book-type that was essentially Dutch, and to make one ofthat kind for ourselves

ought always to be counted among our highest aspirations.

Charles Enschedé

[1] A reference to the types generally called Civilité.

[2] See later in the book, p. 267. Rosart's music needed

two impressions. Charles Enschedé exaggerated the novelty

of mid-i8th-century music types : They had to be much more

complicated than earlier ones to compete with engraving

for instrumental music, but in principle there was nothing

new about them.

[3] It is always difficult to translate the expression 'Pays-Bas'

as Charles Enschedé used it. Here, but not always, he seems

to exclude the modern Belgium, where there were several

first-class native punchcutters, for whom see H.D.L. Vervliet,

Sixteenth-Century Printing Types of the Low Countries, Amsterdam 1968,

chapter 2.

XXV