INTRODUCTION

the heads of the firm decided to part with the outdated and profitless material

and spend the money gained by selling old punches and matrices on typefaces

that were new and in accord with the taste of the time....

Our predecessors afted advisedly, and we cannot blame them for what they

did, though we would willingly give double, perhaps ten times, what they made

by it to undo what they did. They quite understood what they were doing; in 1813

they drew up a new detailed list of the punches and matrices to serve as the firm's

inventory, and with it they put a note as follows :

The inventory has been done anew because of the many changes made necessary by circum¬

stances which have arisen since the two previous ones were made. For we are all agreed that it

is essential to incur extraordinary expenses for ensuring the progress and good reputation of

our foundry, and to meet these expenses we were unanimous in deciding to eliminate and sell

for the best obtainable price, as scrap steel and copper, the punches and matrices that were old

and worn and those that could no longer be of use or advantage. This has been done at inter¬

vals of time. Further, we resolved to use the proceeds for buying new capital letters for titles,

ornamented letters, and other founts of type and sets of matrices for the designs in greatest

demand. All this we have done, and for particulars we refer to the specific list annexed to this

inventory.1

I quote this note as proof that the destruction of a considerable part of the stock

was decided upon only after the most careful reflection ; that there was a desire to

leave a record for the eyes of posterity to show that in a matter of such gravity

action was taken for good reasons. If we could call upon those heads of the firm

to defend themselves, they would doubtless lament as we do the loss of so much

that would now be of great historical interest, but they would not fail to point

out that much that is precious was kept for us although it contributed nothing

to the profits of the business. I will claim, too, that among the sets of matrices that

we still have there are a good many of interest to historians of typography and

amateurs of the arts, but from a commercial point of view are so much old copper.

We cannot fairly blame our ancestors for having converted a part of their equip¬

ment into money: the most we could have asked is that they had shown rather

more discrimination — had spared, perhaps, one set of matrices as an example of

the work of each punchcutter or, better, one complete range of sizes by him.

Our forerunners took the view that, apart from the very ancient relics that I

have mentioned as coming from the stock of Jan Roman & Co., and all the work

of Fleischman, only those matrices were of interest to them that served to cast

type for scripts not commonly available. That explains the preservation of most

of those for Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic. Similarly a good many for typefaces by

Rosart were spared, and so were a number of those for script type and psalm-notes

and the majority of those for flowers and ornaments. Of these our collection is cer¬

ti] This is the 'Spécifique Lijst' referred to in several footnotes on the following pages, see p. 197, note 1,

XXII

INTRODUCTION

tainly worthy to be printed as a specimen-book, and to it might be added typefaces

by Van Dijck and some others which escaped destruction probably by accident.1

Reckoning up the total of material disposed of we reach this result: of the

matrices in the inventory of Ploos van Amstel some 323 sets were sold as old copper;

57 others went later; lastly about 20 sets that were originally made for us.2

The matrices sold realized 479 florins, 4 stivers, and the punches 66 florins,

12 stivers.The money was spent on new typefaces and titling capitals, whose quality

may be judged by their appearance in a specimen-book issued a few years later.3

The extent of our losses will be only too apparent, given the information in

the preceding paragraphs ; but enough remains to warrant a special study. More¬

over, in 1818 our firm acquired the stock of the foundry of Harmsen & Co., suc¬

cessors to J. de Groot of The Hague, and in 1847 it bought the foundry of Elix & Co.

of Amsterdam in which there were many old Dutch matrices at one time the

property of Anthonie & Hendrik Bruyn. To end with, I must not omit to mention

that almost all the matrices of the Berlin typefounder J. F. Unger came into our

possession.

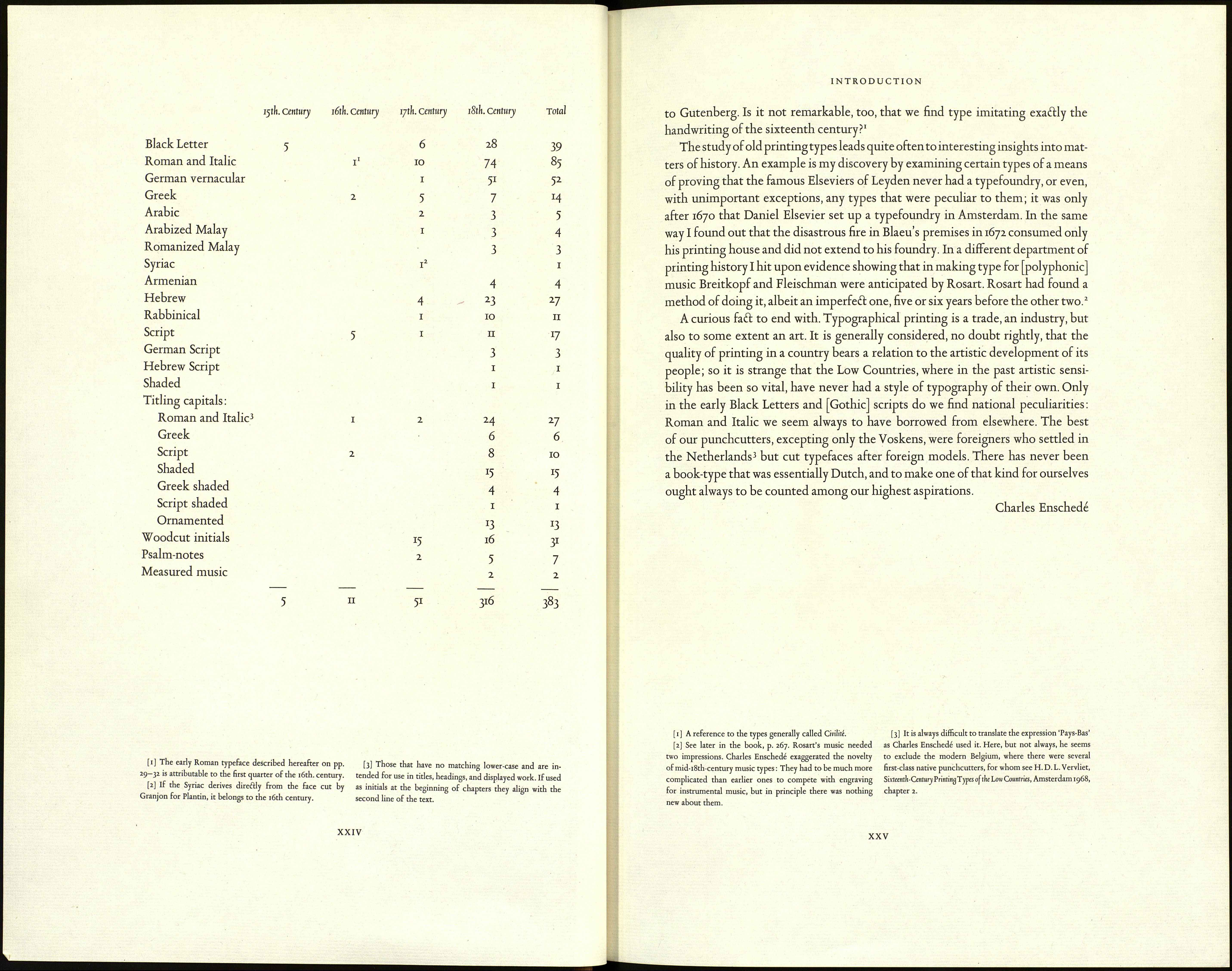

In the following pages I have, to the best of my ability, given a historical account

of 383 different typefaces, which may be classified in tabular form. (See p. 457).

Irrespective of their beauty or interest, I have examined nearly all the typefaces

in our collection. Beauty is so subjective a thing and so much a matter of personal

taste that I should not know how to make a selection based on it; and as for inter¬

est, so many faftors enter into it that I should not wish to put forward my own

judgement of it.

As historical documents all typefaces are of some value; and if allowances

are made for the time when they were cut and the techniques available then,

there are many that are genuinely beautiful though not pleasing to everybody at

the present time.

The fifteenth-century Black Letters used in so many incnnabula make a strong

appeal to us still. It may be that the one Roman typeface of the period still left

to us, perhaps deriving from Peter Schoeffer of Gernsheim, would not be chosen

to print a book now, none the less many a bibliophile will be glad that we have

saved it from oblivion.4

The chalcography of the sixteenth century brings to light the method used

in founding type in the earliest times, while casting in leaden matrices is an indi¬

cation of the essence of the invention which, as it now seems, we must attribute

[1] This was written in 1893. The present book may be Zilverdistel Press of The Hague in this primitive Roman type

regarded as the fulfilment of this ambition. (now thought to be of early 16th-century Cologne origin).

[2] Note that all the punches and matrices were sold for Much later this type was used i.a. for the clandestine edition

scrap: none were allowed to get into the hands of other by W. Hellinga of Van den Vos Reynaerde, Amsterdam 1940

typefounders. (1944). an(i as recently as 1974 for С Reedijk, Erasmus en onze

[3] The quotation from the Gedenkschrtjt of 1893 ends here. Dirt, Haarlem 1974.

[4] In 1913-15 Messrs. Enschedé printed five books for the

XXIII