Part one

Breaking away

from the pen

THIS PART OF THE BOOK is a beginning for some

but a bridge for others. For those who have

mastered the pen, it is a bridge to the wider world of

drawn and three-dimensional letters.

The pen gives a much needed early discipline, but

one can easily become too dependent on it. When you

learn to keep your pen at a constant angle, it sorts out

all your thick and thin strokes for you. Eventually you

may become dissatisfied with its limitations, but find it

difficult to take the next step, which is learning to

draw both sides of each stroke. This gives you more

freedom but less help from the pencil or whichever

other tool you decide to use. You must learn to temper

this freedom with discipline and put it to work to your

own advantage. Keep the best that the pen has taught

you and learn to build on it.

A serious letterer needs a mixture of control and

relaxation. The controlled, disciplined part is obvious.

The relaxation allows individuality to express itself

through the traditional letterforms. So think of your

training as a judicious mixture of these two elements.

The introductory exercises encourage spontaneous

lettering, and are meant to be fun. They show how to

play with letters and introduce the idea of a personal

movement. They also encourage those who have

previously let the pen do most of the work, to start

thinking about solid letters. Different proportions and

stresses give the familiar shapes a new look.

As for discipline, the time-honoured method of

learning lettering was to copy casts of original Roman

inscriptions. In recent years, however, it has been felt

that too much discipline stifles creativity, and that this

method is too repressive. It was therefore banished

from most art schools, along with drawing from the

antique. But you still need to study these classical

forms, as they provide the basis of our alphabet. It does

not much matter whether you copy from the original

second-century incised letters on the base of Trajan's

Column in Rome or from one of the many later

alphabets derived from them. If you cannot find

anything else to begin with, a good book of classic type

faces is not a bad starting-point.

In this section there is a simplified method of

learning to draw Roman capitals. It shows you how to

build on a skeleton made with a broad-edged

carpenter's pencil. Then you are encouraged to think

of Roman capitals as they were first used: as incised

letters.

Letterers need a repertoire of historical letterforms,

both written and incised. These will not necessarily be

copied exactly but used as a basis for creativity.

Experienced letterers do much of their working-out

in their head. As you progress from the experimental

stages, you need enough of a background to help you

conjure up an image of the letter you are aiming at

before you can explore and refine it on paper.

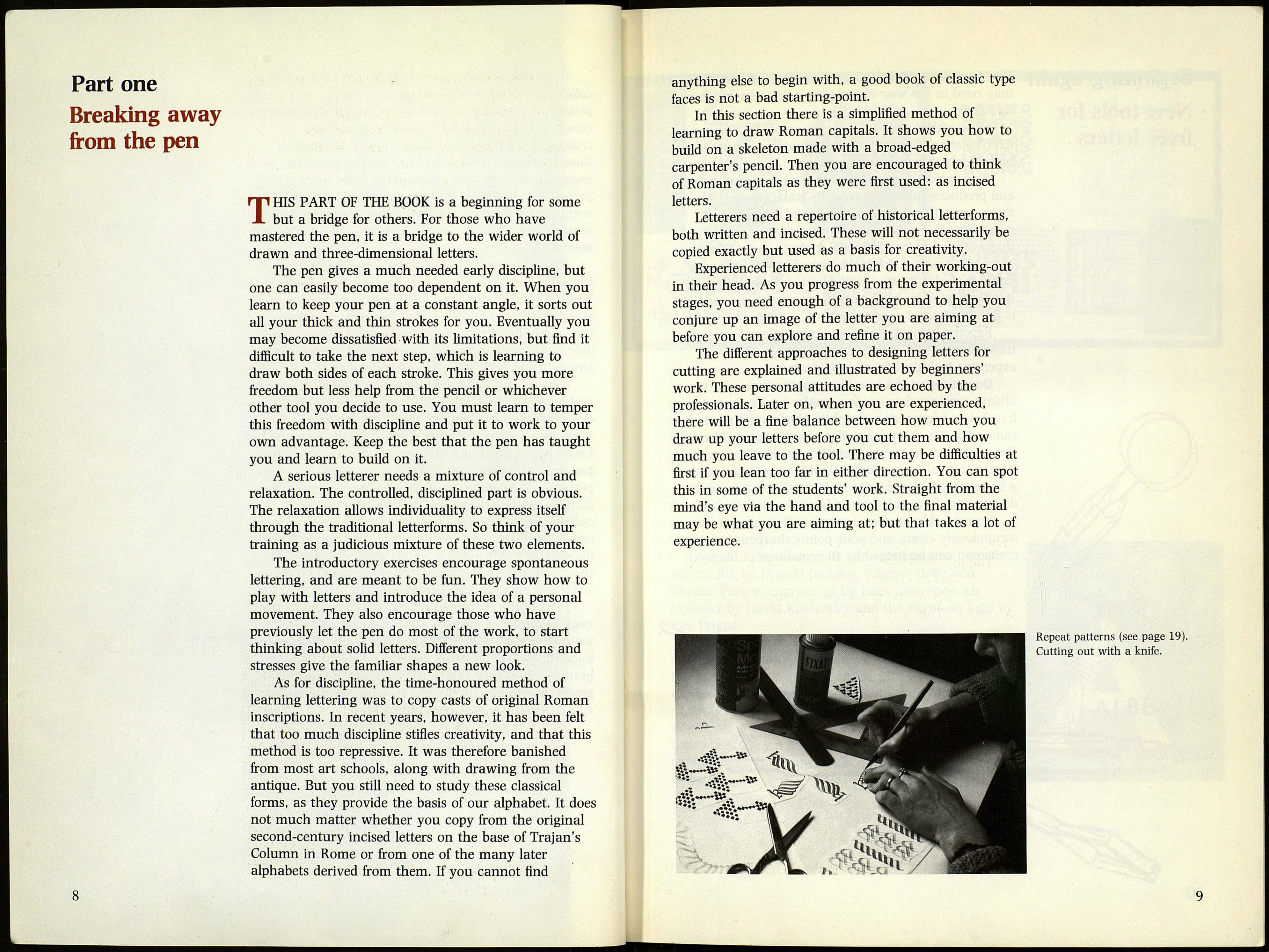

The different approaches to designing letters for

cutting are explained and illustrated by beginners'

work. These personal attitudes are echoed by the

professionals. Later on, when you are experienced,

there will be a fine balance between how much you

draw up your letters before you cut them and how

much you leave to the tool. There may be difficulties at

first if you lean too far in either direction. You can spot

this in some of the students' work. Straight from the

mind's eye via the hand and tool to the final material

may be what you are aiming at; but that takes a lot of

experience.