Briem certainly had an international training: his

formal art education started in his native Iceland and

he studied letterforms in Denmark and Switzerland. He

finished his postgraduate education in London with a

PhD from the Royal College of Art. He described

himself as a designer who specializes in lettering, but

would not call himself a calligraphier. His lectures on

the alphabet are usually within a historical framework.

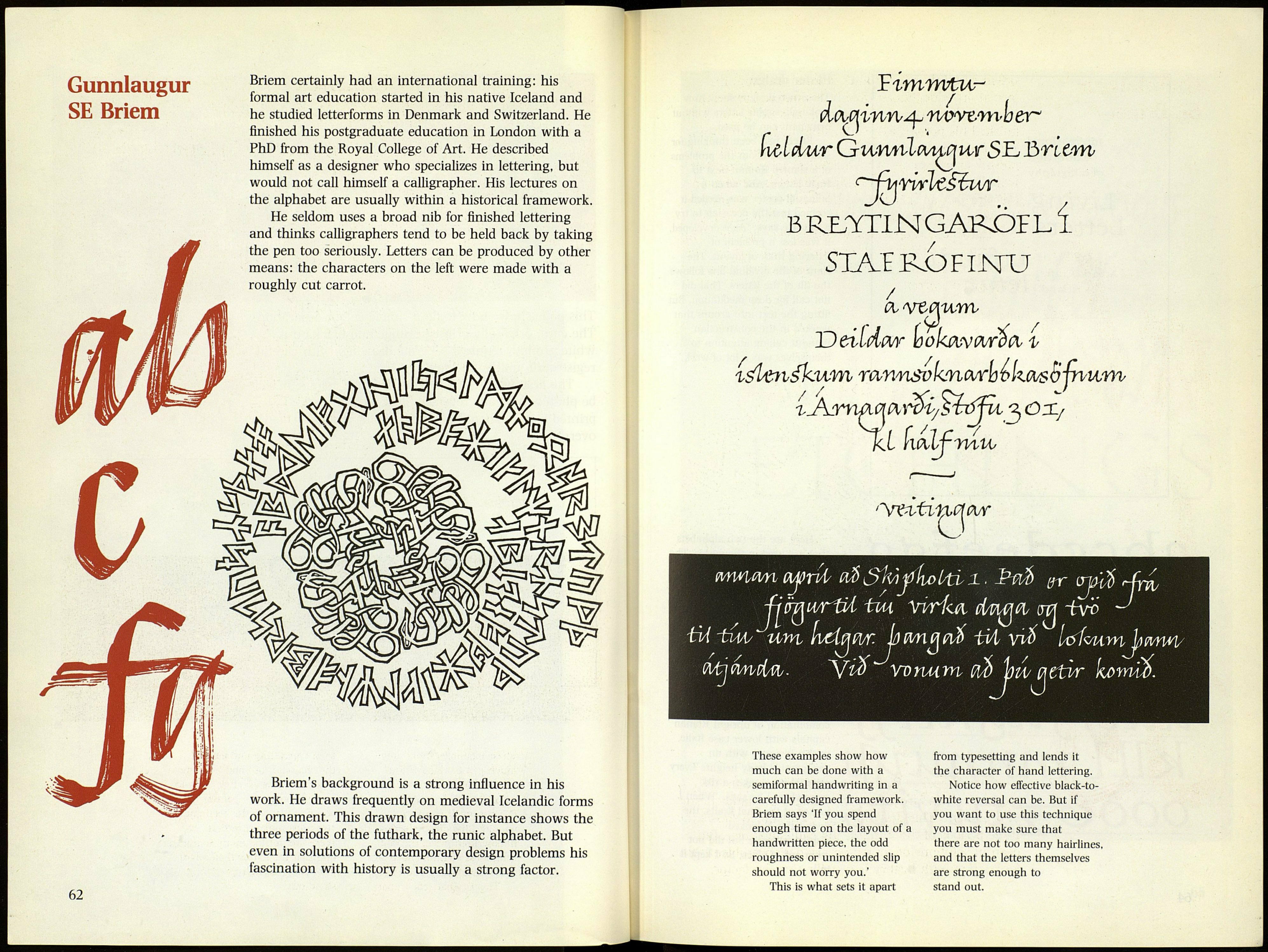

He seldom uses a broad nib for finished lettering

and thinks calligraphers tend to be held back by taking

the pen too seriously. Letters can be produced by other

means: the characters on the left were made with a

roughly cut carrot.

Briem's background is a strong influence in his

work. He draws frequently on medieval Icelandic forms

of ornament. This drawn design for instance shows the

three periods of the futhark, the runic alphabet. But

even in solutions of contemporary design problems his

fascination with history is usually a strong factor.

doictinri^ nvwrnoeir'

mícUtr оѵтльісшйріѵ 5Ь Згіспѵ

В Rb-YTIN GARDIL í

/

SXA.EROFINU

/

(X'Vtc\urrb

mi

Ueildw юокяѵрьгйсг i

гЛ^лшшгді/Ві^рі^ОХ/

■тпи,

'Лге^г'Сьп.ййА'

MWlWl

ótá\V№ÍMj- V¿0 ѵопмт (M) Ьм/ iïttvr komio.

These examples show how

much can be done with a

semiformal handwriting in a

carefully designed framework.

Briem says 'If you spend

enough time on the layout of a

handwritten piece, the odd

roughness or unintended slip

should not worry you.'

This is what sets it apart

from typesetting and lends it

the character of hand lettering.

Notice how effective black-to-

white reversal can be. But if

you want to use this technique

you must make sure that

there are not too many hairlines,

and that the letters themselves

are strong enough to

stand out.