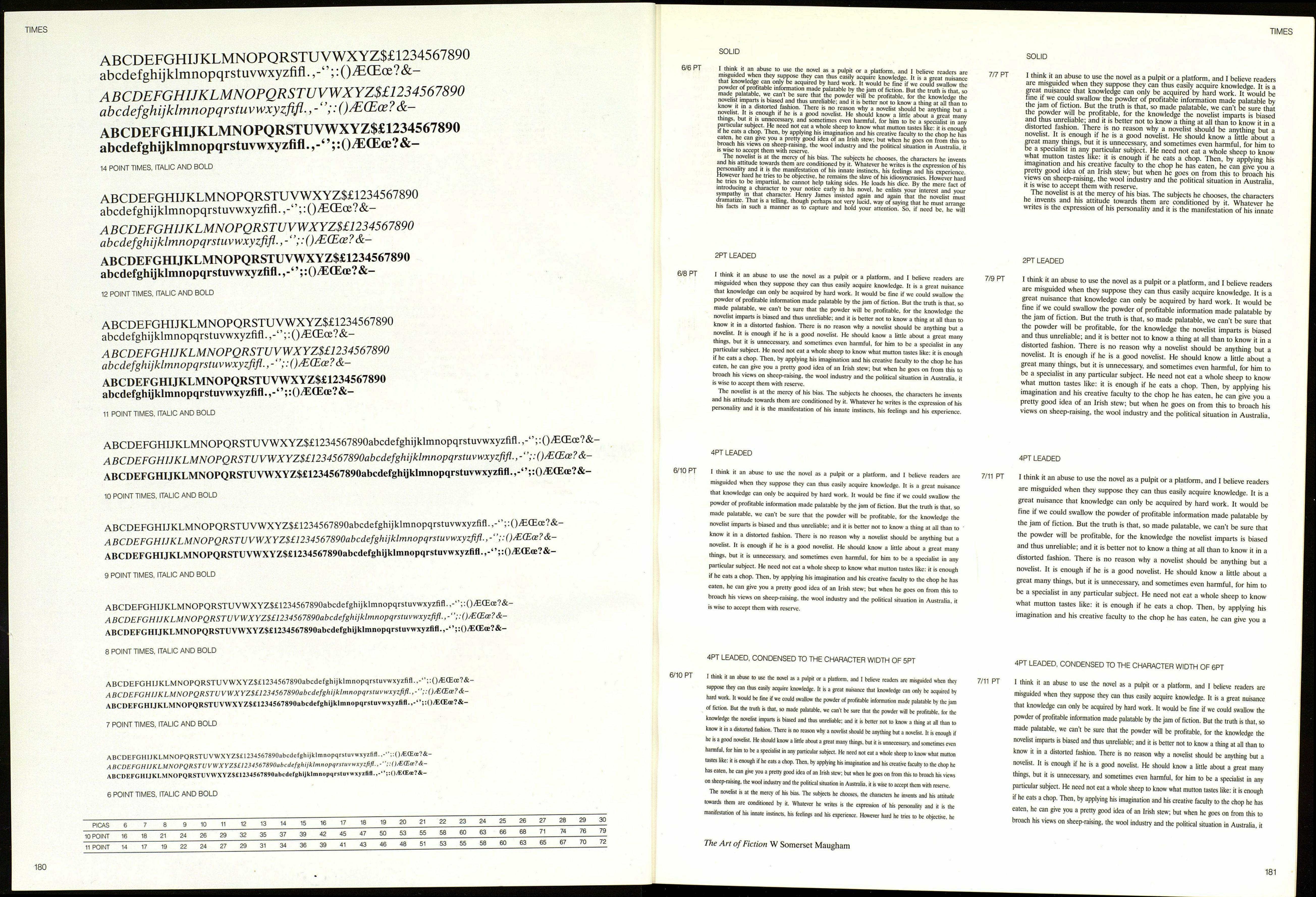

TIMES

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl., ()ÆŒœ? &-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.’ ; : ()ÆŒœ?&-

14 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-l’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl-,-(’;:()ÆŒœ? &-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

12 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl. ()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl-,-'’ ;:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

11 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘,;:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHJJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-";:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

10 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl-,-‘';:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzflfl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

9 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGH IJ KLM NOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl ()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

8 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-”;:0ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTTJVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-‘’;:()ÆŒœ?&-

7 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-”;:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-";:()ÆŒœ?&-

ABCDEFGHI,ÏKLMNOPQRSTUVVVXYZ$£1234567890abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzfifl.,-”î:()ÆŒœ?&-

6 POINT TIMES, ITALIC AND BOLD

PICAS

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

10 POINT

16

18

21

24

26

29

32

35

37

39

42

45

47

50

53

55

58

60

63

66

68

71

74

76

/9

11 POINT

14

17

19

22

24

27

29

31

34

36

39

41

43

46

48

51

53

55

58

60

63

65

67

70

/2

180

TIMES

SOLID

' wh.‘h ь Ѵь use the. novel as a PulPd or a platform, and I believe readers are

misguided when they suppose they can thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a great nuisance

üuuloiawledgB сш only be acquired by hard work. It would be fine if wc could swallow the

powder of profitable information made palatable by the jam of fiction. But the truth is that so

ZÍÍkHmñírF T- “ V a Tre that the powder will be profitable, for the knowledge the

know h 3h' ,h,£unre!,able: and 11 ls bettcr » know a thing at ail than to

SSV. il 3 d,stort?l.tfaahl9n- There ls n° reason why a novelist should be anything but a

ZjV ? en0U8h 'f hC ,S aag00d n0Velist' He should know a litlle about a great many

i к- unnecessary, and sometimes even harmful, for him to be a specialist in any

К ». suujec ní!e nef "“'и?1 a whole sheeP to know what mutton tastes like: it is enough

it he eats a chop. Then, by applying his imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he has

eaten, he can give you a pretty good idea of an Irish stew; but when he goes on from this to

broach his views on sheep-raising, the wool industry and the political situation in Australia it

is wise to accept them with reserve. '

» Iw Zv'ï is at ‘if I?ercy of his bias- ^ subjects he chooses, the characters he invents

and his attitude towards them arc conditioned by it. Whatever he writes is the expression of his

personality and it is the manifestation of his innate instincts, his feelings and his experience

However hard he tries to be objective, he remains the slave of his idiosyncrasies. However hard

he tries to be impartial, he cannot help taking sides. He loads his dice. By the mere fact of

introducing a character to your notice early in his novel, he enlists your interest and vour

SffiS 'ltbat cha!?c,er Henry James insisted again and again that the novelist must

dramatize. That is a telling, though perhaps not very lucid, way of saying that he must arrange

his tacts in such a manner as to capture and hold your attention. So, if need be, he will

SOLID

7/7 PT I think It an abuse to use the novel as a pulpit or a platform, and I believe readers

are misguided when they suppose they can thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a

great nuisance that knowledge can only be acquired by hard work. It would be

tine if we could swallow the powder of profitable information made palatable by

the jam of fiction. But the truth is that, so made palatable, we can’t be sure that

j P°wder "¡ill be profitable, for the knowledge the novelist imparts is biased

and thus unreliable; and it is better not to know a thing at all than to know it in a

distorted fashion. There is no reason why a novelist should be anything but a

novelist. It is enough if he is a good novelist. He should know a little äbout a

great many things, but it is unnecessary, and sometimes even harmful, for him to

be a specialist in any particular subject. He need not eat a whole sheep to know

what mutton tastes like: it is enough if he eats a chop. Then, by applying his

imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he has eaten, he can give you a

pretty good idea of an Irish stew; but when he goes on from this to broach his

views on sheep-raising, the wool industry and the political situation in Australia

it is wise to accept them with reserve.

The novelist is at the mercy of his bias. The subjects he chooses, the characters

he invents and his attitude towards them are conditioned by it. Whatever he

writes is the expression of his personality and it is the manifestation of his innate

2PT LEADED

6/8 PT I think it an abuse to use the novel as a pulpit or a platform, and I believe readers are

misguided when they suppose they can thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a great nuisance

that knowledge can only be acquired by hard work. It would be fine if we could swallow the

powder of profitable information made palatable by the jam of fiction. But the truth is that, so

made palatable, we can't be sure that the powder will be profitable, for the knowledge the

novelist imparts is biased and thus unreliable; and it is better not to know a thing at all than to

know it in a distorted fashion. There is no reason why a novelist should be anything but a

novelist. It is enough if he is a good novelist. He should know a little about a great many

things, but it is unnecessary, and sometimes even harmful, for him to be a specialist in any

particular subject. He need not eat a whole sheep to know what mutton tastes like: it is enough

if he eats a chop. Then, by applying his imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he has

eaten, he can give you a pretty good idea of an Irish stew; but when he goes on from this to

broach his views on sheep-raising, the wool industry and the political situation in Australia, it

is wise to accept them with reserve.

The novelist is at the mercy of his bias. The subjects he chooses, the characters he invents

and his attitude towards them arc conditioned by it. Whatever he writes is the expression of his

personality and it is the manifestation of his innate instincts, his feelings and his experience.

2PT LEADED

7/9 PT I think it an abuse to use the novel as a pulpit or a platform, and I believe readers

are misguided when they suppose they can thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a

great nuisance that knowledge can only be acquired by hard work. It would be

fine if we could swallow the powder of profitable information made palatable by

the jam of fiction. But the truth is that, so made palatable, we can’t be sure that

the powder will be profitable, for the knowledge the novelist imparts is biased

and thus unreliable; and it is better not to know a thing at all than to know it in a

distorted fashion. There is no reason why a novelist should be anything but a

novelist. It is enough if he is a good novelist. He should know a little about a

great many things, but it is unnecessary, and sometimes even harmful, for him to

be a specialist in any particular subject. He need not eat a whole sheep to know

what mutton tastes like: it is enough if he eats a chop. Then, by applying his

imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he has eaten, he can give you a

pretty good idea of an Irish stew; but when he goes on from this to broach his

views on sheep-raismg, the wool industry and the political situation in Australia,

4PT LEADED

6/10 PT I think it an abuse to use the novel as a pulpit or a platform, and I believe readers are

misguided when they suppose they can thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a great nuisance

that knowledge can only be acquired by hard work. It would be fine if we could swallow the

powder of profitable information made palatable by the jam of fiction. But the truth is that, so

made palatable, we can’t be sure that the powder will be profitable, for the knowledge the

novelist imparts is biased and thus unreliable; and it is better not to know a thing at all than to

know it in a distorted fashion. There is no reason why a novelist should be anything but a

novelist. It is enough if he is a good novelist. He should know a little about a great many

things, but it is unnecessary, and sometimes even harmful, for him to be a specialist in any

particular subject. He need not eat a whole sheep to know what mutton tastes like: it is enough

if he eats a chop. Then, by applying his imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he has

eaten, he can give you a pretty good idea of an Irish stew: but when he goes on from this to

broach his views on sheep-raising, the wool industry and the political situation in Australia, it

is wise to accept them with reserve.

4PT LEADED

7/11 PT I think It an abuse to use the novel as a pulpit or a platform, and I believe readers

are misguided when they suppose they can thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a

great nuisance that knowledge can only be acquired by hard work. It would be

fine if we could swallow the powder of profitable information made palatable by

the jam of fiction. But the truth is that, so made palatable, we can’t be sure that

the powder will be profitable, for the knowledge the novelist imparts is biased

and thus unreliable; and it is better not to know a thing at all than to know it in a

distorted fashion. There is no reason why a novelist should be anything but a

novelist. It is enough if he is a good novelist. He should know a little about a

great many things, but it is unnecessary, and sometimes even harmful, for him to

be a specialist in any particular subject. He need not eat a whole sheep to know

what mutton tastes like: it is enough if he eats a chop. Then, by applying his

imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he has eaten, he can give you a

4PT LEADED, CONDENSED TO THE CHARACTER WIDTH OF 5PT

6/10 PT I think it an abuse to use the novel as a pulpit or a platform, and I believe readers are misguided when they

suppose they ran thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a great nuisance that knowledge can only be acquired by

haid work. II would be fine if we could swallow (he powder of profitable information made palatable by the jam

of fiction. But the truth is that, so made palatable, we can’t be sure that the powder will be profitable, for the

knowledge the novelist imparts is biased and thus unreliable; and it is better not to know a thing at all than to

know it in a distorted fashion. There is no reason why a novelist should be anything but a novelist. It is enough if

he is a good novelist. He should know a little about a great many things, but it is unnecessary, and sometimes ewm

harmful, for him lo be a specialist in any particular subject. He need not eal a whole sheep lo know what mutton

tastes like: it is enough if he eats a chop. Then, by applying his imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he

has eaten, he can give you a pretty good idea of an Irish stew: but when he goes on from this to broach his views

on sheep-raising, the wool industiy and the political situation in Australia, it is wise to accept them with reserve.

The novelist is at the mercy of his bias. The subjects he chooses, the characters he invents and his attitude

towards them are conditioned by it. Whatever he writes is the expression of his personality and it is the

manifestation of his innate instincts, his feelings and his experience. However hard he tries to be objective, he

4PT LEADED, CONDENSED TO THE CHARACTER WIDTH OF 6PT

7/11 PT I think it an abuse to use the novel as a pulpit or a platform, and I believe readers are

misguided when they suppose they can thus easily acquire knowledge. It is a great nuisance

that knowledge can only be acquired by hard work. It would be fine if we could swallow the

powder of profitable information made palatable by the jam of fiction. But the truth is that, so

made palatable, we can't be sure that the powder will be profitable, for the knowledge the

novelist imparts is biased and thus unreliable; and it is better not to know a thing at all than to

know it in a distorted fashion. There is no reason why a novelist should be anything but a

novelist. It is enough if he is a good novelist. He should know a little about a great many

things, but it is unnecessary, and sometimes even harmful, for him to be a specialist in any

particular subject. He need not eat a whole sheep to know what mutton tastes like: it is enough

if he eats a chop. Then, by applying his imagination and his creative faculty to the chop he has

eaten, he can give you a pretty good idea of an Irish stew; but when he goes on from this to

broach his views on sheep-raising, the wool industry and the political situation in Australia, it

The Art of Fiction W Somerset Maugham

181