i8o 50. SHADY CHARACTERS

T

Satiffacnone

foi LVIIII

viij.q.i.lcicndu.ip'iJ.q-üii.öilpIiccf.ßboca’tiöt'So.ati

ôcrdiq.xvcnc.ltfoç.|uiClcm.lionn).ru(j"pbo. icipm.

öcobfiu.|cm.c.ft.t Arcbio’.j.q.ij.eiqs ¿ptcr. Hddc

q lug vbqoia Oipi.v.attr. 7 bo с осЬз vnöquccK altare.

7 lUud ma qo Icnpli in. $. Q> anva.v. fjoc bico. vc qa

biligcrcr neat adiplcre qtf m còfdTionc ribicfhnffittrç.*

hoc iiontoipi in rpcmarc qltioruejj pcñs/qz alb cereria

panb9 idem op9magia rncriconii clem co cj no реееаше

45 m co q boc rdcitjj pene lilis cñ lile fun culpa le ad hoc

i j aimmrcrir/iKcnôbicioliutqbocbjillc Donar. аг.|ііІй.o'

lega, if.ccòtrano.pj'tìcd pone Га tilla ctioiic alio anno Confirm >m

jìuùcraj no fenili tinned ad^uctencarl ircraio mòcótV ¡re

етШЖсеоІгІІЬ cumpcr.6 ШсШШ.Шср no. KÄ

j fìrccoìdcrm oc linltdctioe Tide fi lieft actu lanilacicdi fi ПтіГапю)

i rom li maio: ¿¡5 зппл Г teneri tñ cóficcri t» ГапГшссгс imù*

, nc¿lcpilh ѵсІсогстрГип íce9 lino recorder ,v с Гсгіріі, s* aä nô сош

in maria pfcflìòis. iS.7gencralirli qras. v.aur ncdcpir.

bc Dubitare aùr art l'atilhrcent vcl по/ eie q? lànfi aactiot

0cb5¿rerarc.piq.Dí.qclcam9.)cFm;.q.ip.coinpiáf:i:um

iprcaqlcnpli.B.in.ÿ.l5an'iapfcllio.-è.ali|aiir.qi п./

oeft ad ramilioné pene future. £ûq: nôpôr oto oigne

рр cl arc. v> г Гспр li. 0. i pa mb nil 5. ß nunqd prnia; prof

7 qi pluincrcb; q> iwfccir.O q? 111 facro.no по clr,pz

babilis igrantu. ¿.ос refein. vedi. L fi с]а. (ti p (bcio.Ui.

OciívcIcripri.abcpeóicaro.Eiiqibccclrturíoj.Ocípon. o ir -

linicms.Dbomi.ad audicnnâ,^ B5 nunijd fàrilfacri'/ fí™

one libi quietaqspofiirpalaiimplcrc/tctigifuprq.ru. p.4..»mis

2lrcbio.oicitqi ouplep с effect- fatifFacnôieÆIn9JôÜltô

öebiti pero^t peedentw* 2Ш9ерписгіо ciiulbç pcfoii (су

qnnu. jQuo ad fm nô poeqi p |eiumfi vm9caro altert9

iionnu cerar. iQ 110 ad pmiì/li dr porte idem lice iuuari

pollicg alni q Iceii iciuncr.Ôcc9licltiporêsco:palifvcl

1

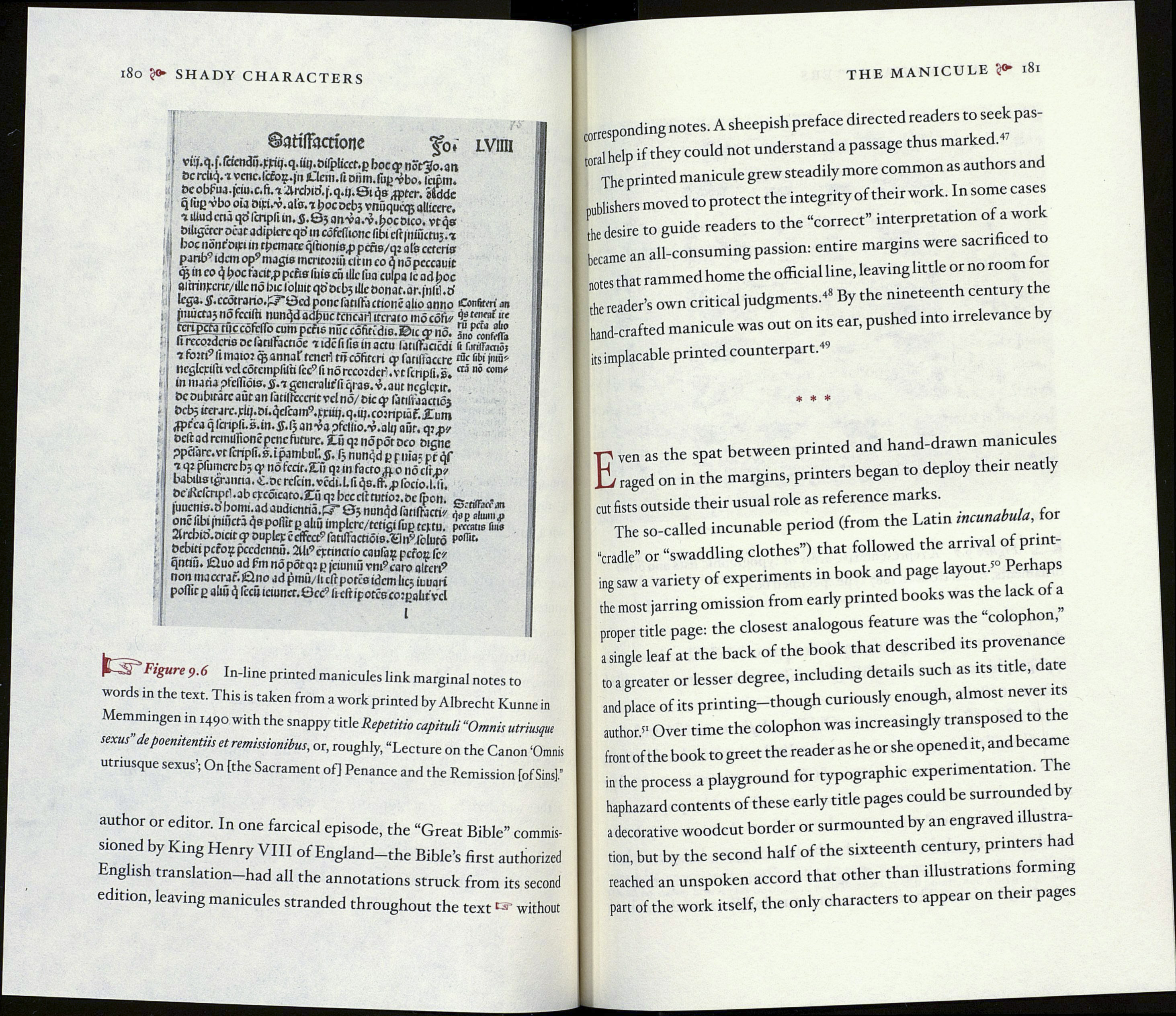

9.6 In-line printed manicules link marginal notes to

words in the text. This is taken from a work printed by Albrecht Kunne in

Memmingen in 1490 with the snappy title Repetitio caphuli “Omnis utriusque

sexus”depoenitentiis etremissionibus, or, roughly, “Lecture on the Canon ‘Omnis

utriusque sexus’; On [the Sacrament of] Penance and the Remission [of Sins].”

author or editor. In one farcical episode, the “Great Bible” commis¬

sioned by King Henry VIII of England-the Bible’s first authorized

English translation-had all the annotations struck from its second

edition, leaving manicules stranded throughout the text ^ without

THE MANICULE ^ 181

pxiespoitdmg notes. A sheepish preface directed readers ^ tas"

„lhelp if they could not understand a passage thus marked.

The printed manicule grew steadily m0[ec0™™°“

Wishers moved to protect the integrity of their wort. In some

*deS,tet°6"' ;e„rire margins were sacrificed to

pul

guide readers to the “correct” interpretation of a work

^ _ . • fn

Ararne an all-consuming passion:

uotesthat rammed home the official line, leaving little or no room tor

the reader's own critical judgments.** Bythe nineteenth century ^

hand-crafted manicule was out on

its implacable printed counterpart

! its ear, pushed into irrelevance by

* * *

r ven as the spat between printed and hand-drawn manicules

b taged on in the margins, printers began to deploy then nea y

cut fists outside their usual role as reference marks.

The so-called incunable period (from the Latin шишЬиІа.ІО,

Wie" or -swaddling clothes") that followed the arriva of prmt-

ing saw a variety of experiments in book and page layout) Perhap

the most jarring omission from early printed books was the lack of a

proper title page: the closes, analogous feature was the colophon

. single leaf a. the back of the book that described .ts provenne

to a greater or lesser degree, including details such as tts ...le, date

sod place of its printing-.hough curiously enough, almost never.

author.51 Over time the colophon was increasingly transpose о

front of the book to greet the reader as he or she opened it, and became

in the process a playground for typographic experimentation. The

haphazard contents of these early title pages could be surrounded by

a decorative woodcut border or surmounted by an engraved illustra¬

tion, but by the second half of the sixteenth century, printers had

reached an unspoken accord that other than illustrations forming

part of the work itself, the only characters to appear on their pages