178 SHADY CHARACTERS

THE MANICULE 179

олп.

;¡t ialiti c(t

■io' Iprob. t

Tw ûfiiûfitü

niniiqjba

DÍairn coßißif

fi dì!ecrö film

rmtoWúiiTdí

firofenftmlia

ист pccöfor

СПІ.Г^мл и.л

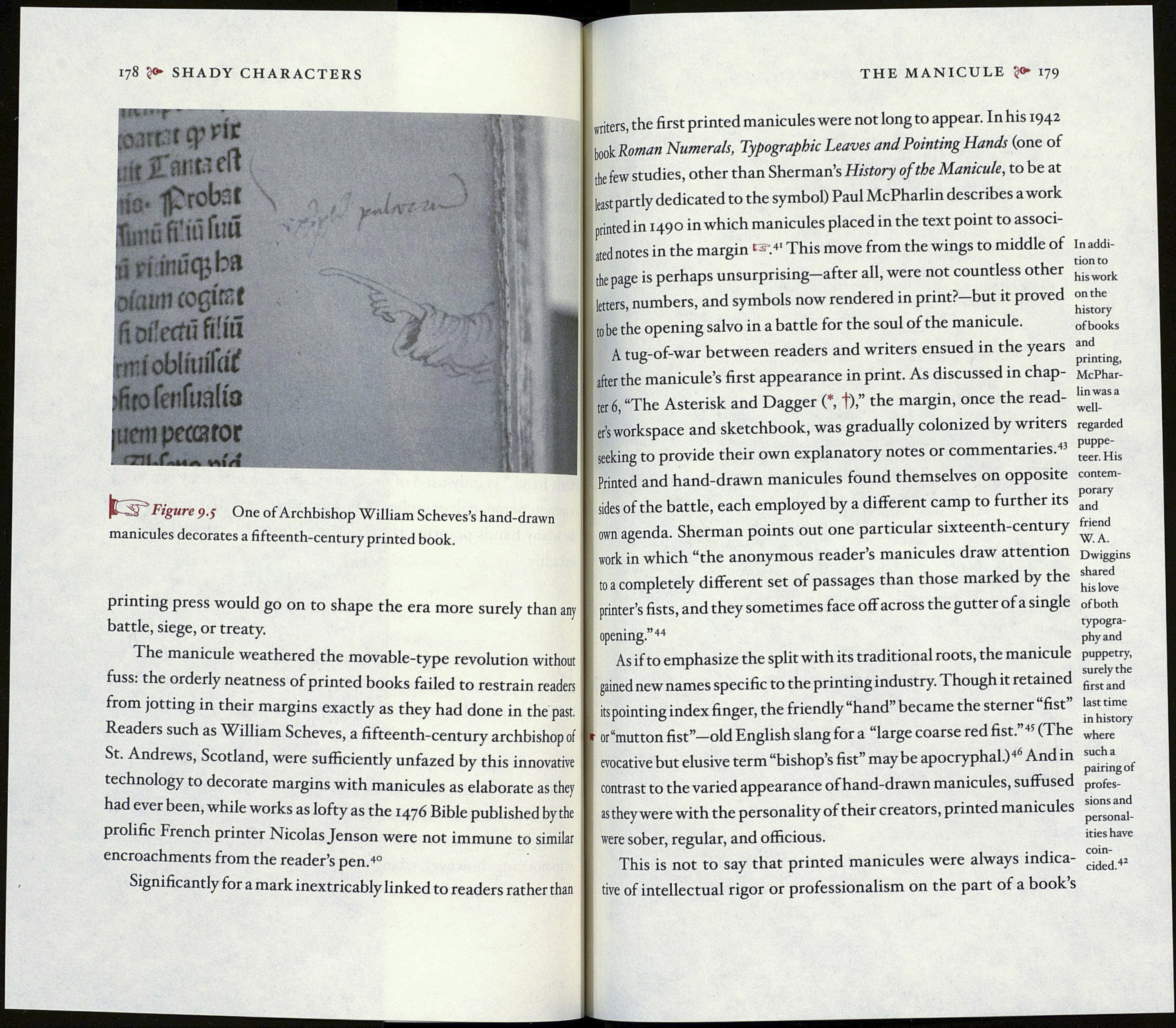

^¿¡'Figure 9.5 One of Archbishop William Scheves’s hand-drawn

manicules decorates a fifteenth-century printed book.

printing press would go on to shape the era more surely than any

battle, siege, or treaty.

The manicule weathered the movable-type revolution without

fuss: the orderly neatness of printed books failed to restrain readers

from jotting in their margins exactly as they had done in the past.

Readers such as William Scheves, a fifteenth-century archbishop of

St. Andrews, Scotland, were sufficiently unfazed by this innovative

technology to decorate margins with manicules as elaborate as they

had ever been, while works as lofty as the 1476 Bible published by the

prolific French printer Nicolas Jenson were not immune to similar

encroachments from the reader’s pen.40

Significantly for a mark inextricably linked to readers rather than

I w¡terS) the first printed manicules were not long to appear. In his 1942

book Roman Numerals, Typographic Leaves and Pointing Hands (one of

,k few studies, other than Sherman’s History of the Manicule, to be at

least partly dedicated to the symbol) PaulMcPharlin describes a work

I printed in 1490 in which manicules placed in the text point to associ-

: ated notes in the margin 's-.4’ This move from the wings to middle of

the page is perhaps unsurprising—after all, were not countless other

letters, numbers, and symbols now rendered in print?—but it proved

tobe the opening salvo in a battle for the soul of the manicule.

A tug-of-war between readers and writers ensued in the years

after the manicule’s first appearance in print. As discussed in chap¬

ter 6, “The Asterisk and Dagger (*, t)>” the margin, once the read¬

er’s workspace and sketchbook, was gradually colonized by writers

seeking to provide their own explanatory notes or commentaries.43

Printed and hand-drawn manicules found themselves on opposite

sides of the battle, each employed by a different camp to further its

own agenda. Sherman points out one particular sixteenth-century

work in which “the anonymous reader’s manicules draw attention

to a completely different set of passages than those marked by the

printer’s fists, and they sometimes face off across the gutter of a single

opening.”44

As if to emphasize the split with its traditional roots, the manicule

gained new names specific to the printing industry. Though it retained

its pointing index finger, the friendly “hand” became the sterner fist

or “mutton fist”—old English slang for a “large coarse red fist.”45 (The

evocative but elusive term “bishop’s fist” may be apocryphal.)4 And in

contrast to the varied appearance of hand-drawn manicules, suffused

as they were with the personality of their creators, printed manicules

were sober, regular, and officious.

This is not to say that printed manicules were always indica¬

tive of intellectual rigor or professionalism on the part of a book s

In addi¬

tion to

his work

on the

history

ofbooks

and

printing,

McPhar-

linwasa

well-

regarded

puppe¬

teer. His

contem¬

porary

and

friend

W.A.

Dwiggins

shared

his love

ofboth

typogra¬

phy and

puppetry,

surely the

first and

last time

in history

where

sucha

pairing of

profes¬

sions and

personal¬

ities have

coin¬

cided.42