170 5^ SHADY CHARACTERS

contracted to finish the book according to the buyer’s taste-adding

family crest to the cover, perhaps, or selecting a color scheme to match

other volumes in his library.9

Books produced in this manner were eye-wateringly expensive

Even the rudely bound, cut-price editions of theological and philo-

sophical tracts produced for universities were far beyond the reach of

the average student.10 In an echo of the earlier culture of the monastic

scriptorium, such impoverished students would sometimes rent the

original exemplar of a book and copy it out by hand."

Having thus shepherded a book through its creation—selecting

its contents, directing its illumination and binding; perhaps even hav¬

ing painstakingly copied it out in the first place-and having spenta

princely sum in doing so, the Renaissance reader was invested in their

book in a way quite unlike the modern consumer. It was second nature

for a book’s owner to brand it, to annotate and embellish it as they

read; to underline pithy phrases and fill the margins with notes.12 The

imperative to take notes as one read moved the seventeenth-century

Jesuit scholar Jeremias Drexel to write that “reading is useless, vain

and silly when no writing is involved, unless you are reading [devotion-

allyj Thomas a Kempis or some such. Although I would not want even

that kind of reading to be devoid of all note-taking.”'3

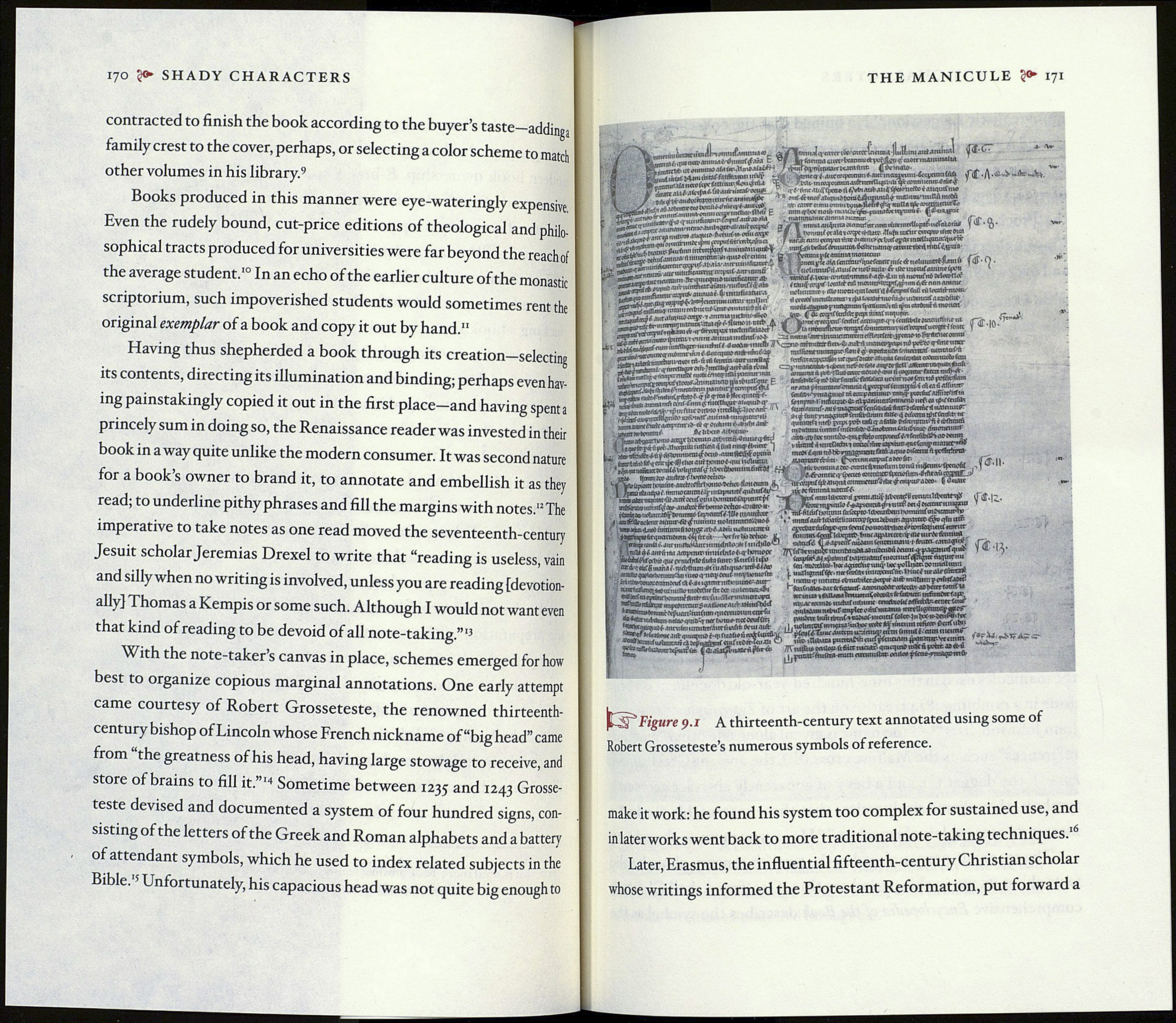

With the note-taker’s canvas in place, schemes emerged for how

best to organize copious marginal annotations. One early attempt

came courtesy of Robert Grosseteste, the renowned thirteenth-

century bishop of Lincoln whose French nickname of “big head” came

from the greatness of his head, having large stowage to receive, and

store of brains to fill it.”и Sometime between 1235 and 1243 Grosse¬

teste devised and documented a system of four hundred signs, con¬

sisting of the letters of the Greek and Roman alphabets and a battery

of attendant symbols, which he used to index related subjects in the

Bible.15 Unfortunately, his capacious head was not quite big enough to

THE MANICULE 171

»«ttmnfrdidMrftf.ifo E “f Jo-(bruna стт-іѵлтийѵо^йсі. у гдоггтдіішмііл

IttdineuiöлЫйс.Ьпѵо.и-«^ / фшГЛупігтеіігюоише (¡Semaio- . . „ . , ,

5Figure p.i A thirteenth-century text annotated using some of

Robert Grosseteste’s numerous symbols of reference.

make it work: he found his system too complex for sustained use, and

in later works went back to more traditional note-taking techniques.

Later, Erasmus, the influential fifteenth-century Christian scholar

whose writings informed the Protestant Reformation, put forward a