io8 $<► SHADY CHARACTERS

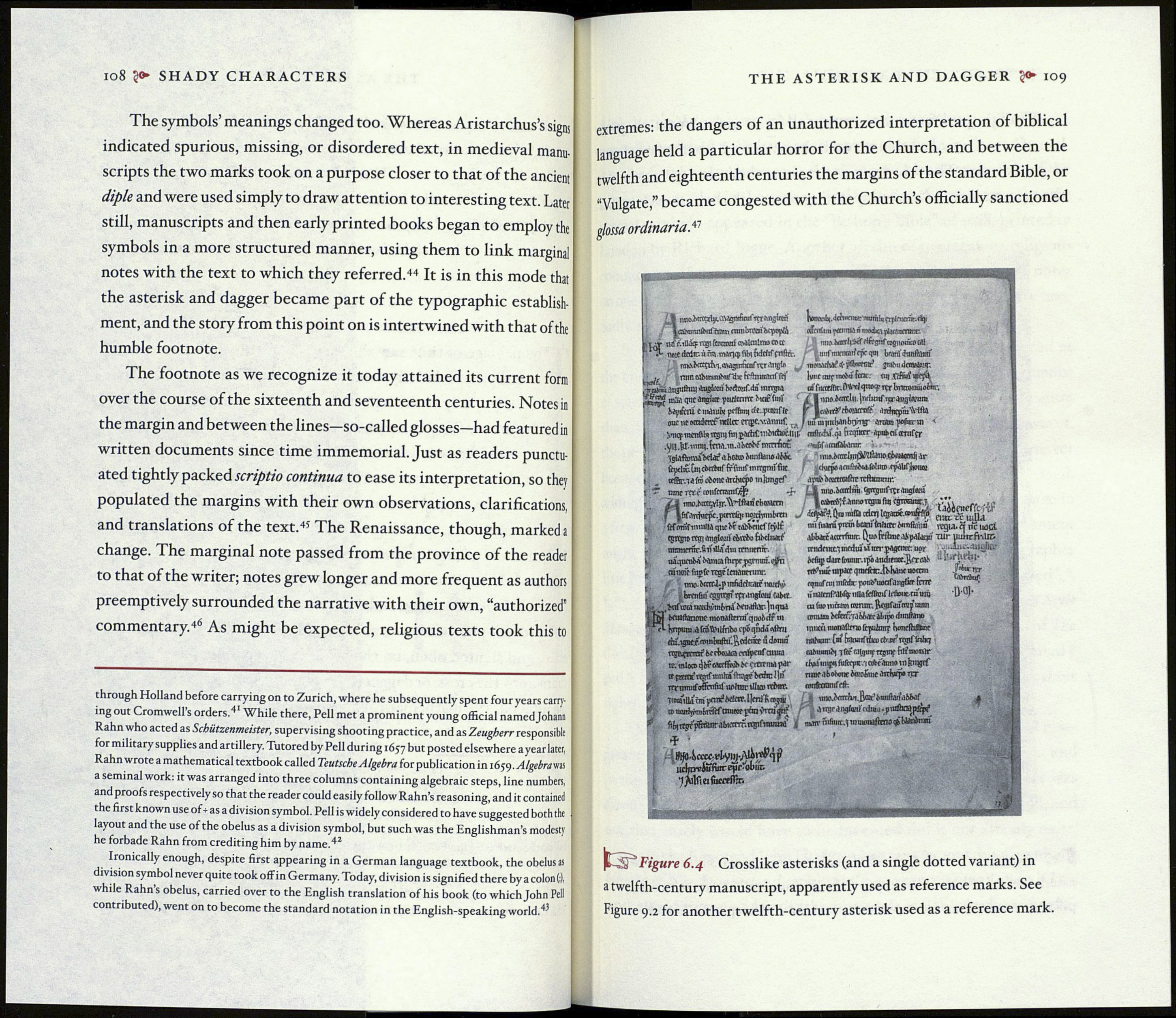

The symbols’ meanings changed too. Whereas Aristarchus’s signs

indicated spurious, missing, or disordered text, in medieval manu¬

scripts the two marks took on a purpose closer to that of the ancient

diple and were used simply to draw attention to interesting text. Later

still, manuscripts and then early printed books began to employ the

symbols in a more structured manner, using them to link marginal

notes with the text to which they referred.44 It is in this mode that I

the asterisk and dagger became part of the typographic establish¬

ment, and the story from this point on is intertwined with that of the

humble footnote.

The footnote as we recognize it today attained its current form

over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Notes in

the margin and between the lines—so-called glosses—had featured in

written documents since time immemorial. Just as readers punctu- !

ated tightly packed scriptio continua to ease its interpretation, so they ;

populated the margins with their own observations, clarifications, i

and translations of the text.45 The Renaissance, though, marked a

change. The marginal note passed from the province of the reader

to that of the writer; notes grew longer and more frequent as authors

preemptively surrounded the narrative with their own, “authorized"

commentary.46 As might be expected, religious texts took this to

through Holland before carrying on to Zurich, where he subsequently spent four years carry¬

ing out Cromwell s orders.4 While there, Pell met a prominent young official named Johann

Rahn who acted as Schützenmeister, supervising shooting practice, and as Zeugherr responsible

for military supplies and artillery. Tutored by Pell during 1657 but posted elsewhere a year later,

Rahn wrote a mathematical textbook called Teutsche Algebra for publication in i6$<).Algebram$

a seminal work: it was arranged into three columns containing algebraic steps, line numbers,

and proofs respectively so that the reader could easily follow Rahn’s reasoning, and it contained

the first known use of* as a division symbol. Pell is widely considered to have suggested both the

layout and the use of the obelus as a division symbol, but such was the Englishman’s modesty

he forbade Rahn from crediting him by name.42

Ironically enough, despite first appearing in a German language textbook, the obelus ss

division symbol never quite took off in Germany. Today, division is signified there by a colon ft

while Rahn’s obelus, carried over to the English translation of his book (to which John Pell

contributed), went on to become the standard notation in the English-speaking world.43

THE ASTERISK AND DAGGER ?<► 109

extremes: the dangers of an unauthorized interpretation of biblical

language held a particular horror for the Church, and between the

twelfth and eighteenth centuries the margins of the standard Bible, or

“Vulgate,” became congested with the Church’s officially sanctioned

glossa ordinaria.47

рдиииииииииииирииииииирииииииИІНИИНІИИИИИНвИН

JA noohtrtçrfy.dVVjmfifiiftçïfingfon IvHirtibf.dtnimtwnrañiii; çrplnimfcdq;

/jebmrnibitfftam сгапЬпинЪсрорЙ овгпСип penn« п modici piattonane

т-у xte^.tUikpregifononiсвіішігаососс inuxbatritôiTHfcyiifœgitomcetfl

л- níut drdtr. à fin .талер libi fidcíifpifbr. nitfпипта»'q>c qm lyumdtmfiann

mw.tarçïhi. оцдшікпГrer Лigfo monachal рАялт.^ grab« danMurr

rmn tubimmbuCdic frfhnnanf frj’ Hmtffltf mobdftnc: оц Tiffin utrçfo

-•roiraú aujufhni Ъхфт bcrtwif.dn inrrgia en fotrtíftr. 0>Ы ф«кр rçr bmonwowtr.

tnto que tJïçtet piirimirr binr (oiï /1 uno.bmthi. jndimfщ-Jugiivnm

btpécm с mAïubi prffmii df.ptœific p pr.i^rrÿ*rf»o¡acmíf «ЫпсрпЛѴДОа

eue titecndereftieficc enjK.v.amuf. гд J ou ni|mbdnbijrnr ¿таи pofiurin <

Vncpincuftbi тгдіц ftnçarMmbuhoajii-' mßwhd.qJ brtfwr rtpabcutrrnffr

•VU .Wahibi. ftm.ni.abttW' imrrfirf щОГ.тгіаімпгг

jgtafìmu&ditf л boîm tentai* .lMc. тлкясІіл^ЙЙіію. фпш fj ir

têydiu Ciu ebrrhnf frfimf inmpi»fw fhirjwdniftpbu.foîitto qálifhoiwi

«fflr.l à fro obonc .trducpo 111 fongrf aw* boirtralhr тсйжгопт

■ paîtrçtf сміГсгапіГДр mio-btm-liraTgrrguifTtr.tiigftvu

imhaa^fr.Viftri cba\um

fif.mfiirpc.jxmiqt ngdtmibrm

üforrifvinilli qttfbr tdhbéucf irÿtf

nrtïgie regi iuglwiï efcrebo fibcliatf

mnnrrnr.fi tfala dui rmiitnrf.

uaqumbi' hùuica ffirprygrninï. oÿn

nmic fngCr Tcgf lownrrunr.

, mio-bftrrJjP infarinati iwtftÿ

‘ , brenfin eggtrgi грушами fabit

V,- , bnftou tiouiivnibnd bethifidr- ]n qui

11Й wa

Ai’.igBe.rfpmbnfhi'.ÇvfdeiiC iî domn

regayrerni’ ЬссЪоіш rrrfpeof шша

te. tnloœ qbf cÄtfioib bt çrrrrmà par

te firme regif miiha ftu\gé betftn 1 |n

rrrmmifoftiiiul uolmr tliiœ itimr.

Itwailld fin pont1 bdete. IJeruk ntpu

Tcjkrb¡fannoTtginftq ftprarar.] A*Vi .л

JiWytfiQramiaакцйвзахтАіф

mi fuiru ptvm (icmítohrrr bonfttì» regia, tic nocí

■M'

ivyt,

.\bb*t.\ctrrfnur. (\uo trihue .lipikqá’ nir uiurrfi\liri

tnidnitt'imedtuuttn-ç^cnrc.ugr

befup dair tnmr.ipó indirmc.^erab “ *

uti’mr tupücr qmrihc.h*htoc uocn» V^rrcr

rqnnfrui liißtlr ponb’uonfdngtítr frnf

ii itílmU’Jbfq,- tiUaftflhnf hfioue.ruuro

tu fuo ni tr.iiii mmur. Jcgifaiíстар umn

nmuin bffof.7dbb.nr atipo dimflauo

uiutti monaúmo ftpuimre Kunrfhfltmf

trahmir Ы framiifdinjclrjif’iTgirihhq

úüuimubj ifte r.)hjuif Tíjuif fitfiuonlf

thbi’iiiipu fuferpu л ciibctouo^n biqgrf

nioe.ibobonr tooSme arrfutpe пт

mrrflrtnnifefr.

І uilo.btrrchn.^Cìt'òaii/tip'dbòdf

ічаііИ nq j»i» uuw.i|\iu niwa —- (

шиЫк-тіл^шшгѵігаіитаігг .1 mir S ¡фа (Ани

1 йгймт-угпикнВЙоип^ЬйгАиш

? '

. HJfl.íscccr-v

ш^тгсйГітиг ey г^оЬііь

^lfietihcreflb

ІіЗС Figure 6.4 Crosslike asterisks (and a single dotted variant) in

a twelfth-century manuscript, apparently used as reference marks. See

Figure 9.2 for another twelfth-century asterisk used as a reference mark.