104 SHADY CHARACTERS

Гн

1TAV

_ „ * и

;.ftNWU№

г-рІОДХ0£ГС'

ІѴШОН^СІП^О)

nfíC-

'cciutpriCiunïK:

^I^NriUAN

фшгпигпье

ttníVU,HEW

T,D°V"rnPH

âSYTfïN .

r A..UJUUn [>

( ХЕ0ѴНОЙ ГТІГІ

N^-OFIC’ AYdb

ЧОиЛІЛААІИи

pa

■v ОунЦ

ЕІСГП

ЦтН

14 ni

u lu

• MEI

0 U0>

• AVtd

Fl

ni

-ГТГ

DYj

POI

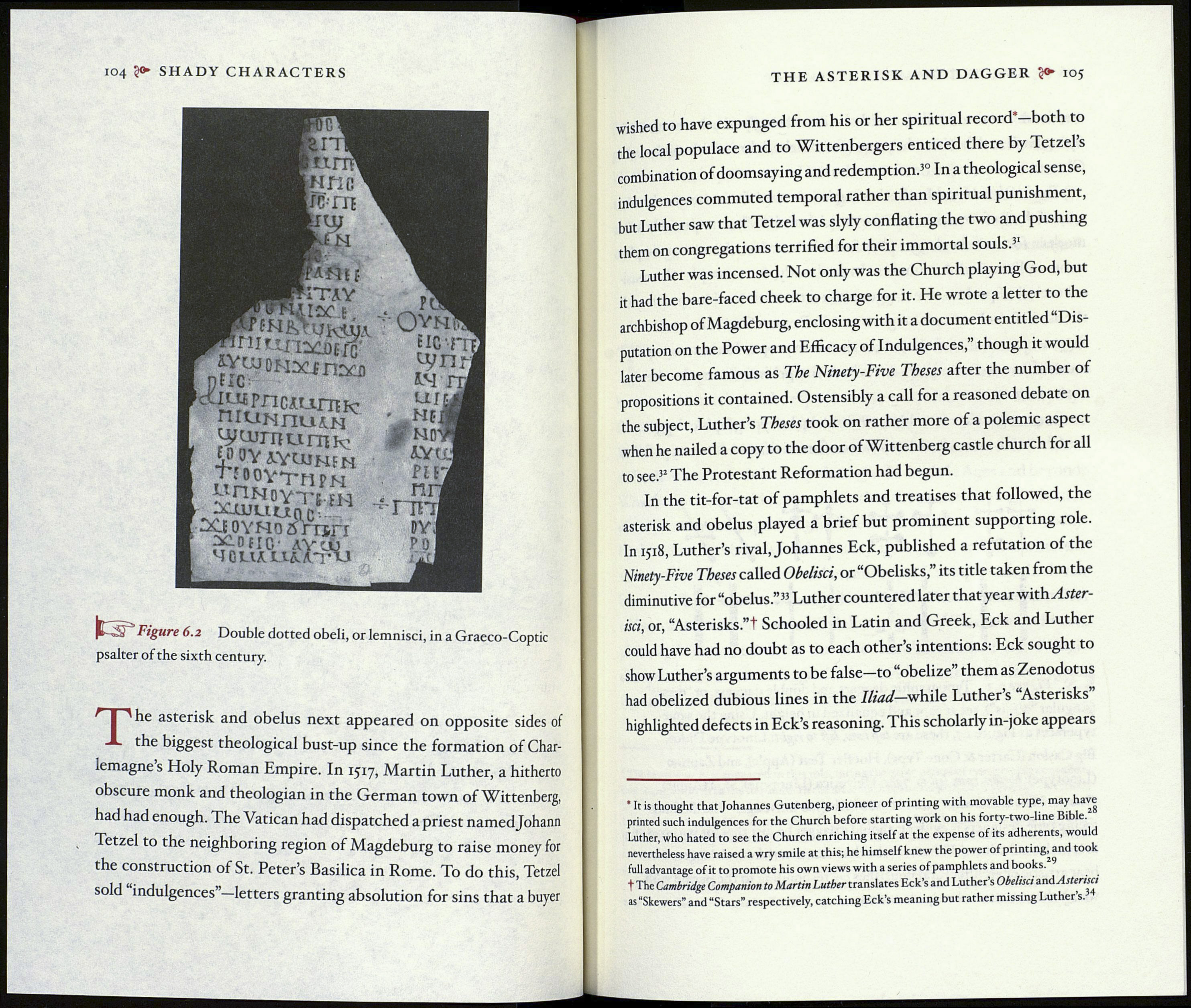

r-—SV Figure 6.2 Double dotted obeli, or lemnisci, in a Graeco-Coptic

psalter of the sixth century.

r I л I*e asterisk and obelus next appeared on opposite sides of

the biggest theological bust-up since the formation of Char¬

lemagne’s Holy Roman Empire. In 1517, Martin Luther, a hitherto

obscure monk and theologian in the German town of Wittenberg,

had had enough. The Vatican had dispatched a priest named Johann

Tetzel to the neighboring region of Magdeburg to raise money for

the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. To do this, Tetzel

sold indulgences”—letters granting absolution for sins that a buyer

THE ASTERISK AND DAGGER 105

wished to have expunged from his or her spiritual record*-both to

the local populace and to Wittenbergers enticed there by Tetzel’s

combination of doomsaying and redemption.30 Ina theological sense,

indulgences commuted temporal rather than spiritual punishment,

but Luther saw that Tetzel was slyly conflating the two and pushing

them on congregations terrified for their immortal souls.31

Luther was incensed. Not only was the Church playing God, but

it had the bare-faced cheek to charge for it. He wrote a letter to the

archbishop of Magdeburg, enclosing with it a document entitled “Dis¬

putation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences,” though it would

later become famous as The Ninety-Five Theses after the number of

propositions it contained. Ostensibly a call for a reasoned debate on

the subject, Luther’s Theses took on rather more of a polemic aspect

when he nailed a copy to the door of Wittenberg castle church for all

to see.32 The Protestant Reformation had begun.

In the tit-for-tat of pamphlets and treatises that followed, the

asterisk and obelus played a brief but prominent supporting role.

In 1518, Luther’s rival, Johannes Eck, published a refutation of the

Ninety-Five Theses called Obelisci, or “Obelisks,” its title taken from the

diminutive for “obelus.”33 Luther countered later that year with Aster-

isci, or, “Asterisks.”t Schooled in Latin and Greek, Eck and Luther

could have had no doubt as to each other’s intentions: Eck sought to

show Luther’s arguments tobe false—to obelize themasZenodotus

had obelized dubious lines in the Iliad.—while Luther s Asterisks

highlighted defects in Eck’s reasoning. This scholarly in-joke appears

• It is thought that Johannes Gutenberg, pioneer of printing with movable type, may have

printed such indulgences for the Church before starting work on his forty-two-line Bible.

Luther, who hated to see the Church enriching itself at the expense of its adherents, would

nevertheless have raised a wry smile at this; he himself knew the power of printing^and took

full advantage of it to promote his own views with aseries of pamphlets and books,

t The Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther translates Eck’s and Luther’s Obelisci and Asterischi

as “Skewers” and “Stars” respectively, catching Eck’s meaning but rather missing Luther s.