70 SHADY CHARACTERS

& & & &

&&ё&

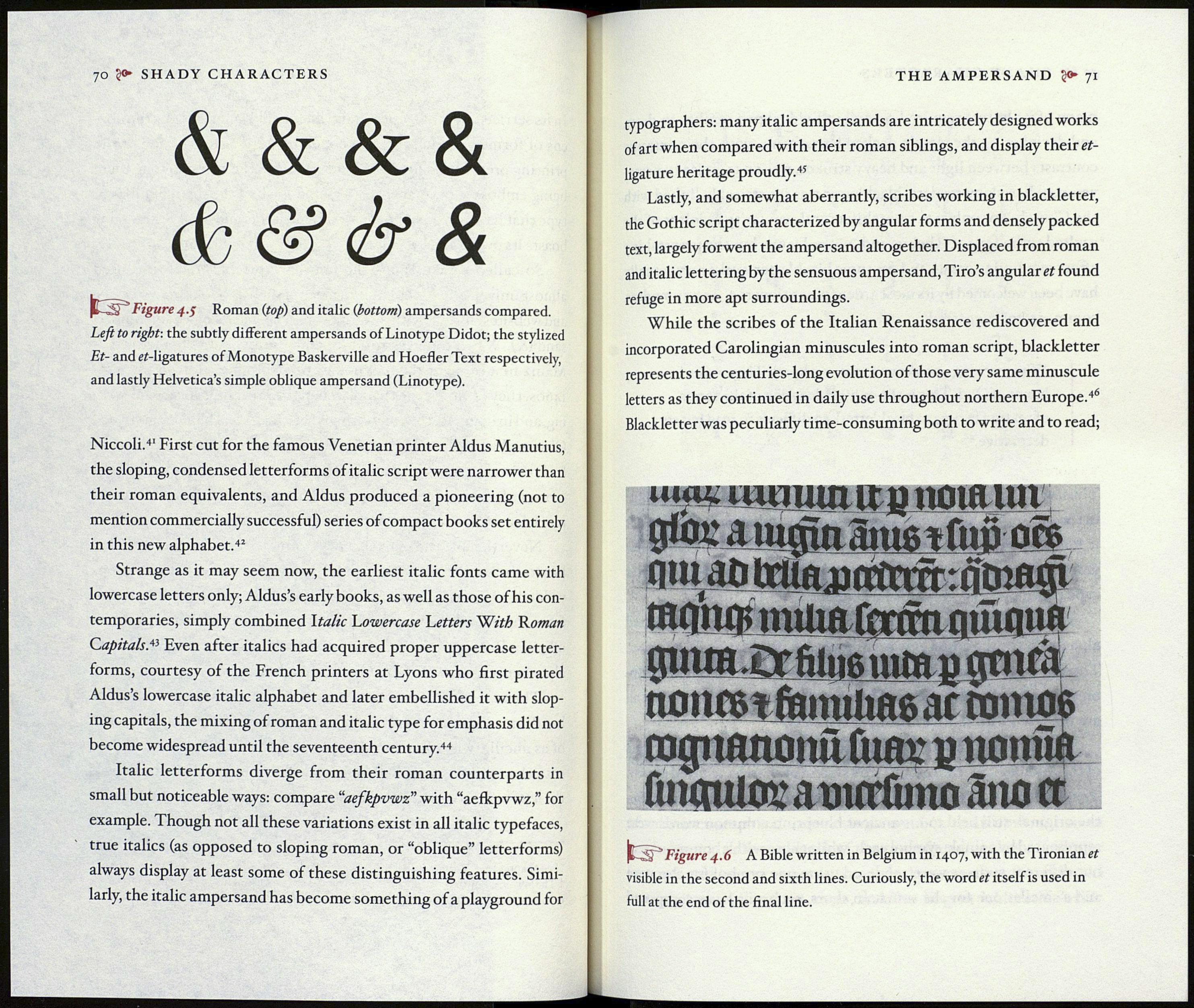

Figure 4.5 Roman (top) and italic (bottom) ampersands compared.

Left to right-, the subtly different ampersands of Linotype Didot; the stylized

Et- and ei-ligatures of Monotype Baskerville and Hoefler Text respectively,

and lastly Helvetica’s simple oblique ampersand (Linotype).

Niccoli.4' First cut for the famous Venetian printer Aldus Manutius,

the sloping, condensed letterforms of italic script were narrower than

their roman equivalents, and Aldus produced a pioneering (not to

mention commercially successful) series of compact books set entirely

in this new alphabet.42

Strange as it may seem now, the earliest italic fonts came with

lowercase letters only; Aldus’s early books, as well as those of his con¬

temporaries, simply combined Italic Lowercase Letters With Roman

Capitals.43 Even after italics had acquired proper uppercase letter¬

forms, courtesy of the French printers at Lyons who first pirated

Aldus’s lowercase italic alphabet and later embellished it with slop¬

ing capitals, the mixing of roman and italic type for emphasis did not

become widespread until the seventeenth century.44

Italic letterforms diverge from their roman counterparts in

small but noticeable ways: compare “aefkpvwz” with “aefkpvwz,” for

example. Though not all these variations exist in all italic typefaces,

true italics (as opposed to sloping roman, or “oblique” letterforms)

always display at least some of these distinguishing features. Simi-

larly, the italic ampersand has become something of a playground for

THE AMPERSAND <><► 71

typographers: many italic ampersands are intricately designed works

of art when compared with their roman siblings, and display their et-

ligature heritage proudly.4S

Lastly, and somewhat aberrantly, scribes working in blackletter,

the Gothic script characterized by angular forms and densely packed

text, largely forwent the ampersand altogether. Displaced from roman

and italic lettering by the sensuous ampersand, Tiro’s angular et found

refuge in more apt surroundings.

While the scribes of the Italian Renaissance rediscovered and

incorporated Carolingian minuscules into roman script, blackletter

represents the centuries-long evolution of those very same minuscule

letters as they continued in daily use throughout northern Europe.46

Blackletter was peculiarly time-consuming both to write and to read;

uwuin ir p nom un

9% л щ cym gme t flifr ore

qm at> ІШптТітіг: nomcp

ЩЩЩ mum fmmnmmjo

gmm.Cr fiammm g 0t»rà

nmimtfamüws ас готоб

rotpmnontifum; р noniía

fuuntiotaumfuno âno et

|Е1;Й ''Figure 4.6 A Bible written in Belgium in 1407, with the Tironian et

visible in the second and sixth lines. Curiously, the word et itself is used in

full at the end of the final line.