66 5е* SHADY CHARACTERS

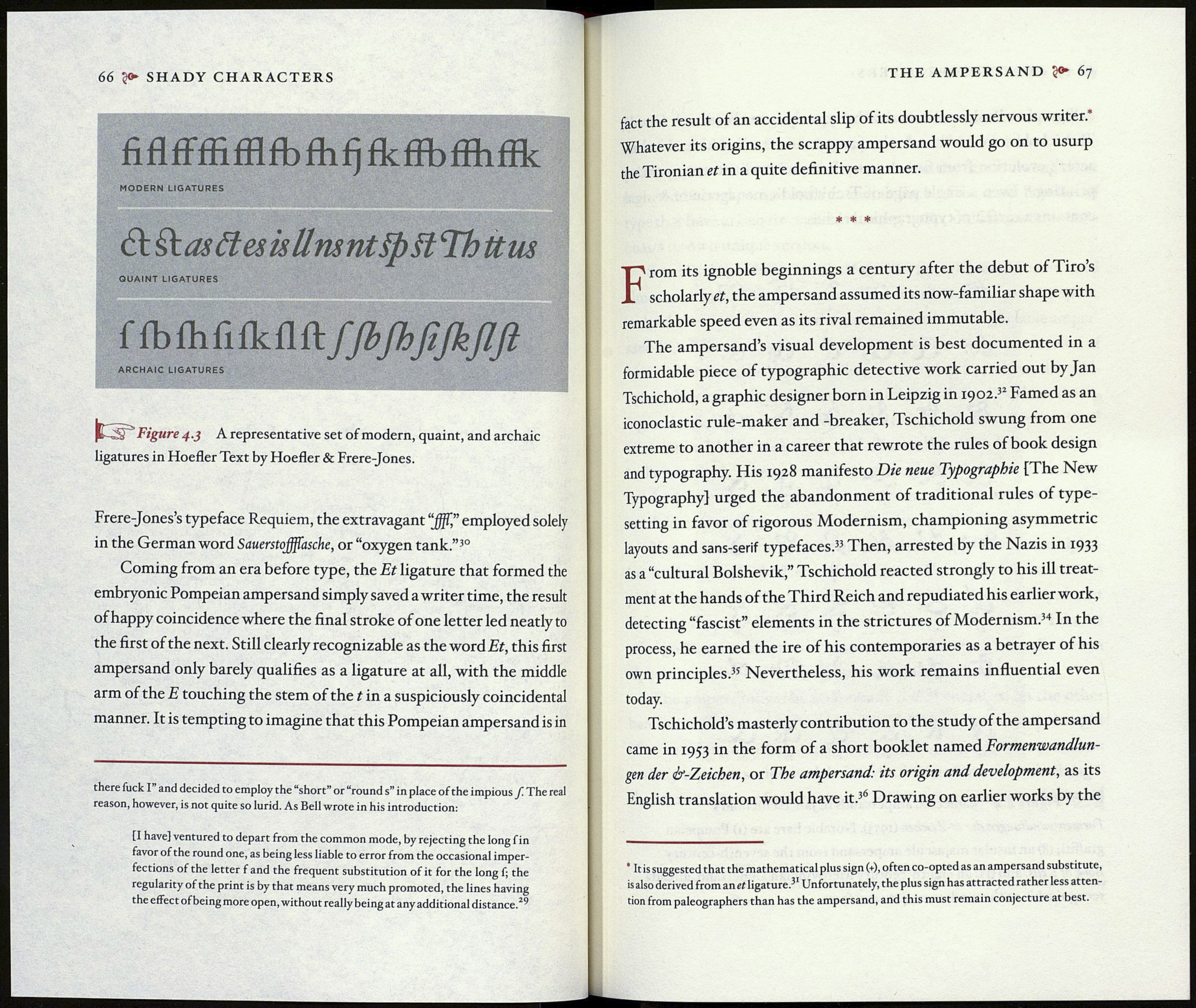

fi fl ffffi ffl fb fli fj fk ffb ffh fik

MODERN LIGATURES

&.§ta$£teshümM$pEtTbttu8

QUAINT LIGATURES

fíbíbfiíkílfl:

ARCHAIC LIGATURES

Figure 4.3 A representative set of modern, quaint, and archaic

ligatures in Hoefler Text by Hoefler & Frere-Jones.

Frere-Jones’s typeface Requiem, the extravagant “jfff” employed solely

in the German word Sauerstojfffasche, or “oxygen tank.”30

Coming from an era before type, the Et ligature that formed the

embryonic Pompeian ampersand simply saved a writer time, the result

of happy coincidence where the final stroke of one letter led neatly to

the first of the next. Still clearly recognizable as the word Et, this first

ampersand only barely qualifies as a ligature at all, with the middle

arm of the E touching the stem of the t in a suspiciously coincidental

manner. It is tempting to imagine that this Pompeian ampersand is in

there fuck I and decided to employ the “short” or “round s” in place of the impious У The real

reason, however, is not quite so lurid. As Bell wrote in his introduction:

[I have} ventured to depart from the common mode, by rejecting the long f in

favor of the round one, as being less liable to error from the occasional imper¬

fections of the letter f and the frequent substitution of it for the long f; the

regularity of the print is by that means very much promoted, the lines having

the effect of being more open, without really being at any additional distance.2^

THE AMPERSAND 67

fact the result of an accidental slip of its doubtlessly nervous writer. '

Whatever its origins, the scrappy ampersand would go on to usurp

the Tironian et in a quite definitive manner.

* * *

From its ignoble beginnings a century after the debut of Tiro’s

scholarly et, the ampersand assumed its now-familiar shape with

remarkable speed even as its rival remained immutable.

The ampersand’s visual development is best documented in a

formidable piece of typographic detective work carried out by Jan

Tschichold, a graphic designer born in Leipzig in 1902.32 Famed as an

iconoclastic rule-maker and -breaker, Tschichold swung from one

extreme to another in a career that rewrote the rules of book design

and typography. His 1928 manifesto Die neue Typographie [The New

Typography] urged the abandonment of traditional rules of type¬

setting in favor of rigorous Modernism, championing asymmetric

layouts and sans-serif typefaces.33 Then, arrested by the Nazis in 1933

as a “cultural Bolshevik,” Tschichold reacted strongly to his ill treat¬

ment at the hands of the Third Reich and repudiated his earlier work,

detecting “fascist” elements in the strictures of Modernism.34 In the

process, he earned the ire of his contemporaries as a betrayer of his

own principles.35 Nevertheless, his work remains influential even

today.

Tschichold’s masterly contribution to the study of the ampersand

came in 1953 in the form of a short booklet named Formenwandlun¬

gen der if-Zeichen, or The ampersand: its origin and development, as its

English translation would have it.36 Drawing on earlier works by the

* It is suggested that the mathematical plus sign (+), often co-opted as an ampersand substitute,

is also derived from an et ligature.^1 Unfortunately, the plus sign has attracted rather less atten¬

tion from paleographers than has the ampersand, and this must remain conjecture at best.