64 SHADY CHARACTERS

utility of Tiro’s system ensured that his et sign would considerably

outlive both its creator and its sponsor.'9 This was not, however, the

storied ampersand: when Tiro created his so-called Tironian et, or-/,

the ampersand was still more than a century away.20

Recalled from exile after only a year, Cicero returned to public

life by degrees. Enjoying a renaissance after Caesar’s assassination,

the veteran orator finally fell victim to the shifting sands of Roman

politics in 43 вс, proscribed by the newly ascendant Mark Antony and

assassinated by his soldiers.21 Legend has it that Antony’s wife Fulvia

was so glad to be free of Cicero’s oratorical powers that she pulled

the tongue from his severed head and skewered it with hairpins.22

Meanwhile, Tiro’s career blossomed after his former master’s death;

in the increasingly bureaucratic Empire his secretarial skills earned

him a comfortable retirement on a farm of his own, where he would

die peacefully at one hundred years old.23 His eponymous shorthand,

and his et, would remain common currency for a further millennium

after that.

* * *

When the ampersand first came to light a century after Cicero

had delivered the Catiline Orations, it emphatically did not

issue from the grandees of the Roman establishment; instead, it came

quite literally straight from the streets. If the Tironian et was Tiro’s

brainchild, the ampersand was an orphan: its creator is not known,*

and the closest it comes to a parent is the anonymous first-century

graffiti artist who scrawled it hastily across a Pompeian wall.25

The myth of Tiro as creator of the ampersand is a persistent one. In Imperium, the first part

of his fictionalized life of Cicero, the author Robert Harris has his narrator Tiro humbly (and

erroneously) declare: “I can modestly claim to be the man who invented the ampersand.”24

THE AMPERSAND 65

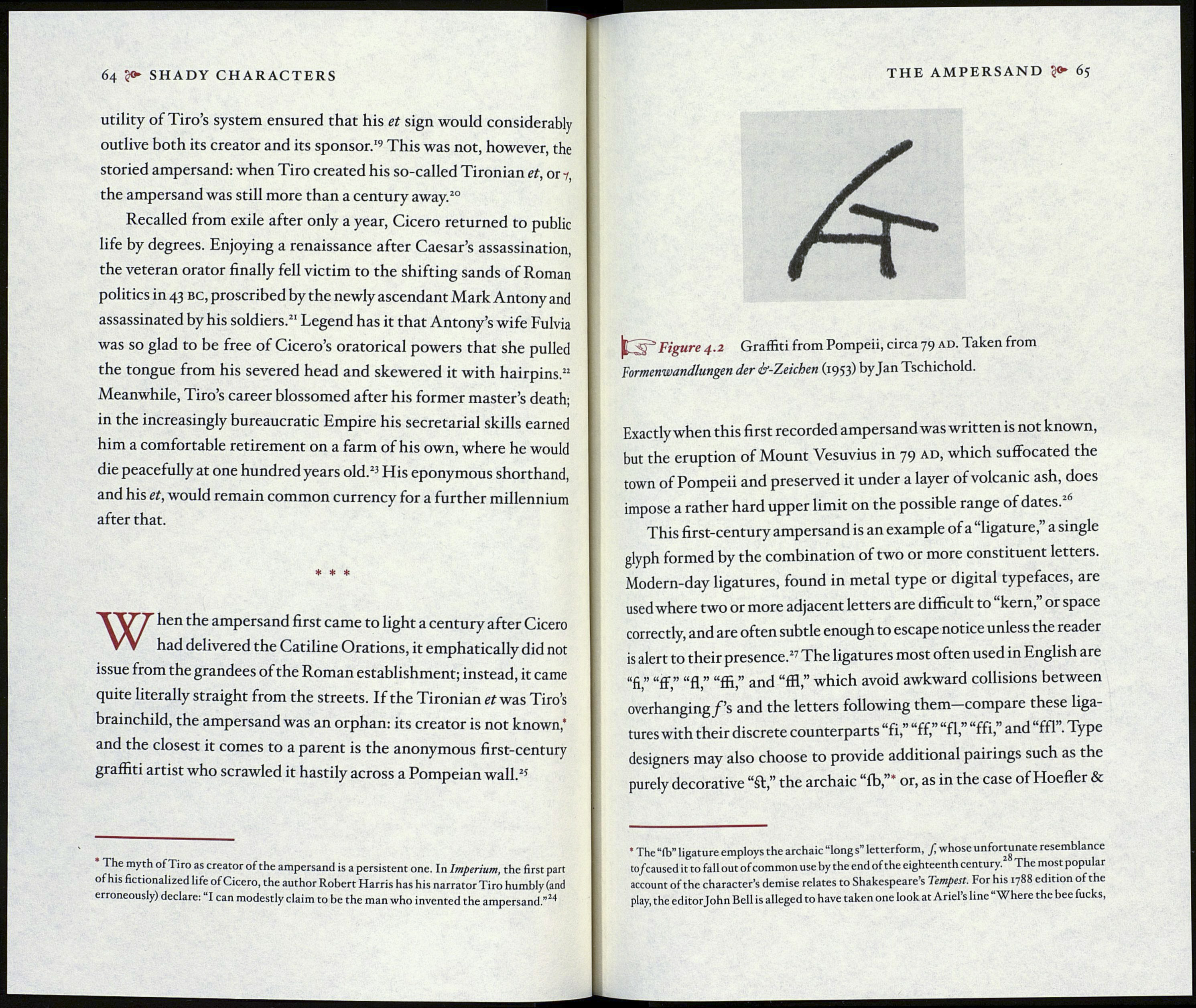

Figure 4.2 Graffiti from Pompeii, circa 79 ad. Taken from

Formenwandlungen der ¿r-Zetchen (1953) byjan Tschichold.

Exactly when this first recorded ampersand was written is not known,

but the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 ad, which suffocated the

town of Pompeii and preserved it under a layer of volcanic ash, does

impose a rather hard upper limit on the possible range of dates.

This first-century ampersand is an example of a “ligature,” a single

glyph formed by the combination of two or more constituent letters.

Modern-day ligatures, found in metal type or digital typefaces, are

used where two or more adjacent letters are difficult to kern, or space

correctly, and are often subtle enough to escape notice unless the reader

is alert to their presence.27 The ligatures most often used in English are

“fi,” “ff,” “fi,” “ffi,” and “ffl,” which avoid awkward collisions between

overhanging/’s and the letters following them—compare these liga¬

tures with their discrete counterparts “fi,” “ff,” “fi,” “ffi,” and ffl . Type

designers may also choose to provide additional pairings such as the

purely decorative “ft,” the archaic “fb,”* or, as in the case of Hoefler &

* The “ib” ligature employs the archaic “long s” letterform, f, whose unfortunate resemblance

to/caused it to fall out of common use by the end of the eighteenth century.2 The most popular

account of the character’s demise relates to Shakespeare’s Tempest. For his 1788 edition of the

play, the editor John Bell is alleged to have taken one look at Ariel’s line “Where the bee fucks,