62 ?<► SHADY CHARACTERS

The conspiracy was ended, but it would cost Cicero his political career.

By flouting the due process of law he had given the reformists (not

least among them a certain general named Gaius Julius Caesar) the

means to persecute him in the courts; four years after the conspiracy,

an embattled and conspicuously isolated Cicero fled to Macedonia."

Cicero’s turbulent life could have filled any number of books, and

being an ardent self-promoter, he made a game attempt to write at least

a few of them himself. He published his speeches as pamphlets to pro¬

mulgate his views; he wrote a variety of philosophical treatises during

his time in exile, and his voluminous correspondence was hoarded by

his closest friend, Atticus, and later published by Cicero’s indispensable

secretary, Tiro.'3 Most apposite to this story, though, is the manner in

which Tiro recorded his master’s spoken words.

Born a slave of Cicero’s household (but later freed, styling himself

Marcus Tullius Tiro), Tiro was a gifted scribe who became Cicero’s

secretary, biographer, and confidant, making himself, as Cicero wrote

to Atticus, “marvelously useful [..in every department of business

and literature.”14 After a tour of Greece some years earlier, Cicero

had come away impressed by Greek shorthand and directed Tiro to

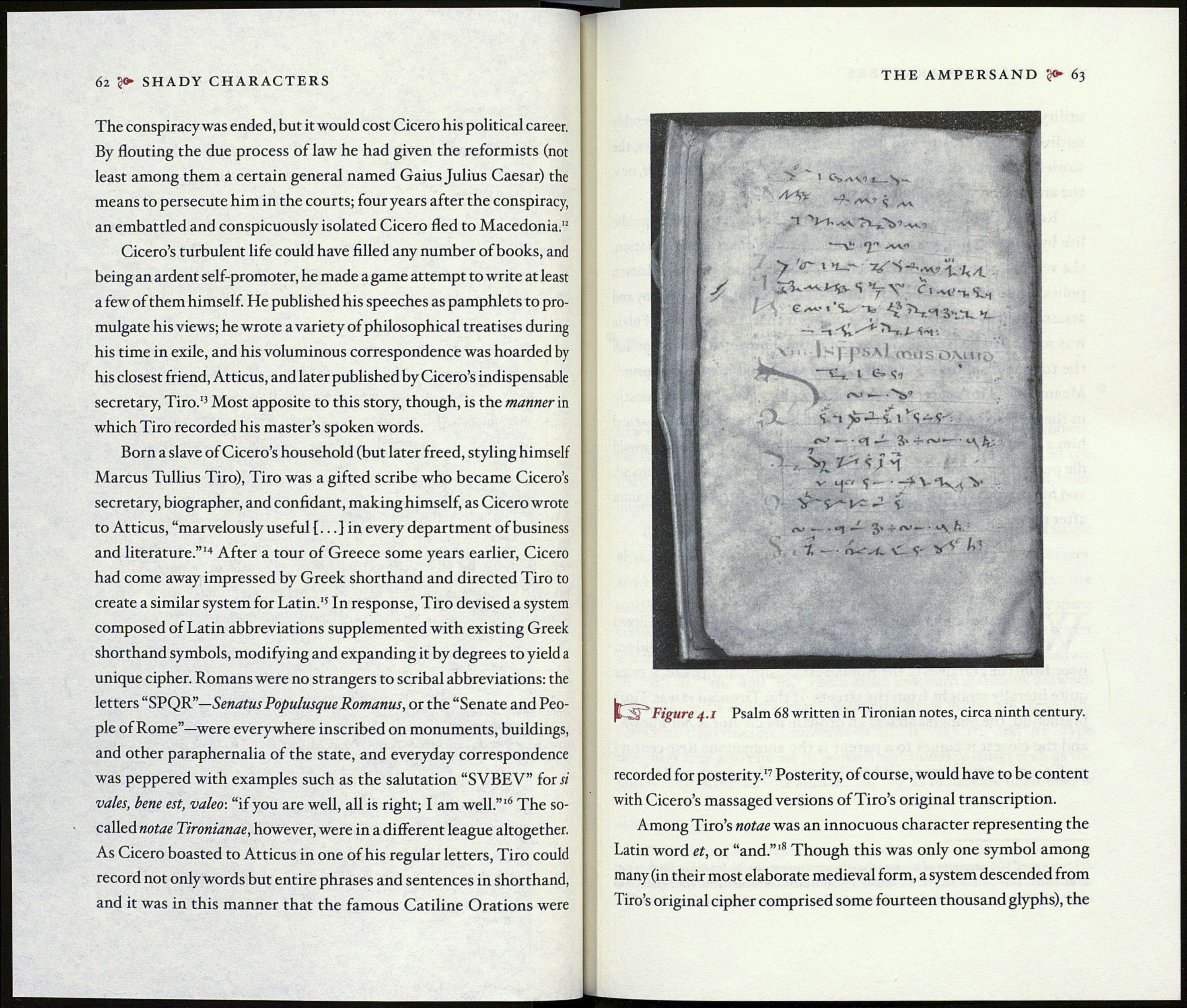

create a similar system for Latin.15 In response, Tiro devised a system

composed of Latin abbreviations supplemented with existing Greek

shorthand symbols, modifying and expanding it by degrees to yield a

unique cipher. Romans were no strangers to scribal abbreviations: the

letters “SPQR’’—Senatus Populusque Romanus, or the “Senate and Peo¬

ple of Rome”—were everywhere inscribed on monuments, buildings,

and other paraphernalia of the state, and everyday correspondence

was peppered with examples such as the salutation “SVBEV” for si

vales, bene est, valeo: “if you are well, all is right; I am well.’”6 The so-

called notae Tironianae, however, were in a different league altogether.

As Cicero boasted to Atticus in one of his regular letters, Tiro could

record not only words but entire phrases and sentences in shorthand,

and it was in this manner that the famous Catiline Orations were

THE AMPERSAND 63

Figure 4.1 Psalm 68 written in Tironian notes, circa ninth century.

recorded for posterity.17 Posterity, of course, would have to be content

with Cicero’s massaged versions of Tiro’s original transcription.

Among Tiro’s notae was an innocuous character representing the

Latin word et, or “and.”18 Though this was only one symbol among

many (in their most elaborate medieval form, a system descended from

Tiro’s original cipher comprised some fourteen thousand glyphs), the