234 5^ SHADY CHARACTERS

a means to distinguish humorous posts from more serious content.”

On September 19,1982, faculty member Scott E. Fahlman entered the

debate with the following message:

I propose that [sic] the following

character sequence for joke markers:

Read it sideways. Actually, it is probably

more economical to mark things that are

NOT jokes, given current trends. For

this, use:

: - (76

The rest is Internet history: Fahlman’s expressive, minimal icons

became an integral part of online communication, if not always

a welcome one.77 These “smileys,” as they came to be known, were

effectively the first online irony marks, indicating that what has gone

before should be read on a second, humorous level.78 The smiley itself,

however, is far older than its modern habitat. At the same time that

Marcellin Jobard, Alcanter de Brahm, and Hervé Bazin were con¬

cocting new marks to convey irony, a series of Anglo-Saxon writers

turned to the limited palette of the typewriter keyboard to create

anthropomorphic indications of joy, sadness, and irony. Emoticons

recur throughout modern history like defenestrations in Prague.

Though it is difficult to nail down the emoticon’s first appear¬

ance in print, one likely contender appears in the New Tork Times’

1862 transcript of a speech made by President Abraham Lincoln.79

The transcript records the audience’s response to Lincoln’s droll

introduction as “(applause and laughter ;)”—containing an abbrevi¬

ated form of the same winking smiley that Tara Liloia would later

reject as a suitable tool for denoting sarcasm. Without corroborating

IRONY AND SARCASM 235

evidence, however, it is impossible to decide whether this is a genuine

emoticon. Counting in its favor, the transcript was typeset by hand,

before mechanical typesetting brought with it the risk of gummed-

up Linotypes accidentally transposing characters, and so it is plau¬

sible that rather than the more grammatically sensible was

intentional.80 Moreover, later audience reactions to the same speech

appear between square brackets rather than parentheses, reinforc¬

ing the likelihood that this particular interjection was deliberately

typeset as such. On the negative side, this single was the only such

“emoticon” in the entire speech, and the rest of the text suffers from

enough typographic errors that it cannot be guaranteed to have been

a calculated addition.8' Though its form is undeniably familiar, the

precise meaning of this first emoticon remains unknown.

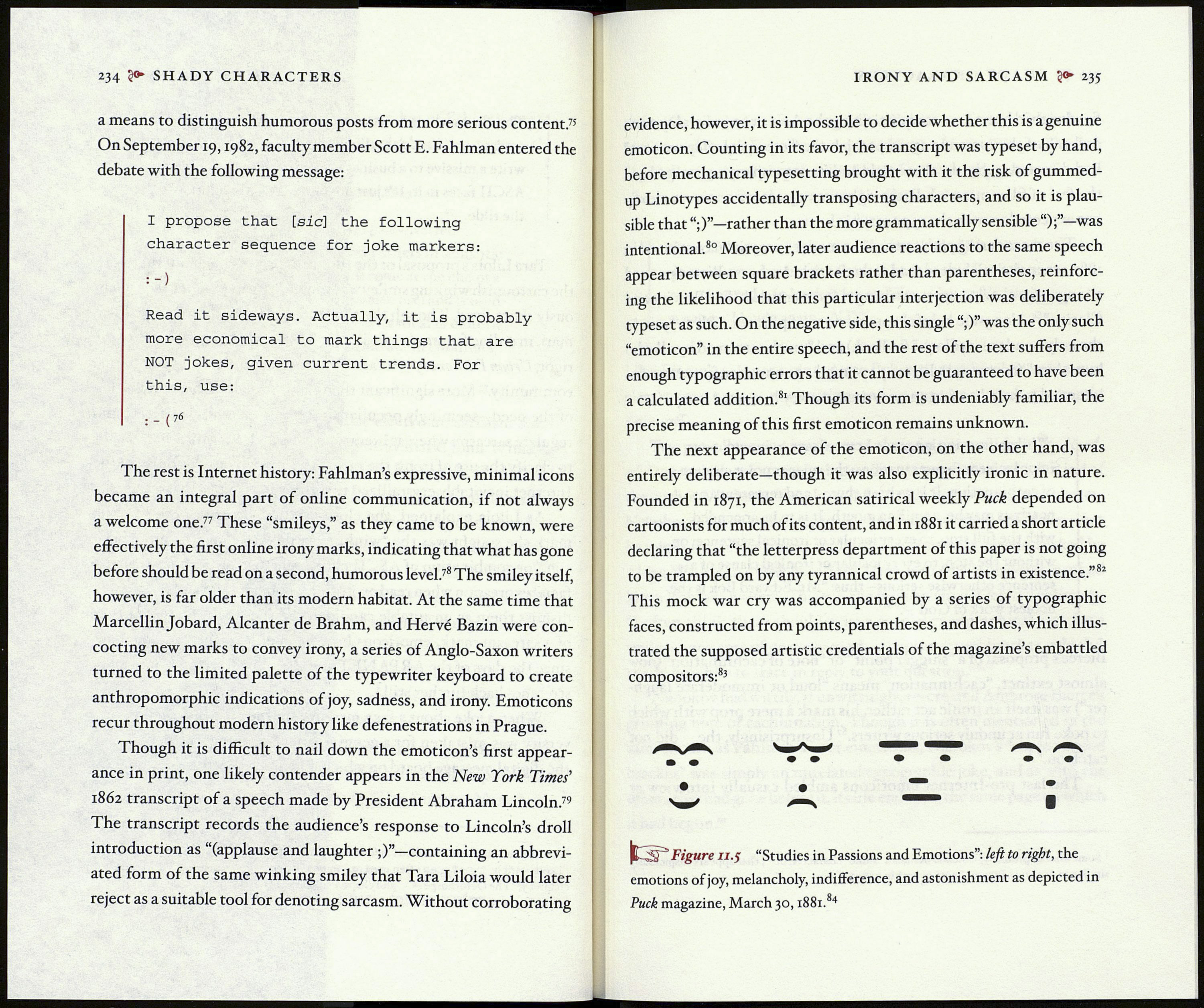

The next appearance of the emoticon, on the other hand, was

entirely deliberate—though it was also explicitly ironic in nature.

Founded in 1871, the American satirical weekly Puck depended on

cartoonists for much of its content, and in 1881 it carried a short article

declaring that “the letterpress department of this paper is not going

to be trampled on by any tyrannical crowd of artists in existence.”82

This mock war cry was accompanied by a series of typographic

faces, constructed from points, parentheses, and dashes, which illus¬

trated the supposed artistic credentials of the magazine’s embattled

compositors:83

• • •

W — ■

Jy' Figure и.5 “Studies in Passions and Emotions”: left to right, the

emotions of joy, melancholy, indifference, and astonishment as depicted in

Puck magazine, March 30,1881.84