196 SHADY CHARACTERS

• §1

яѵт-._ ...

XYtÎIM

’ t’WNdT'

ЛА’НГИС]

“•CûSMjy

r ^ altLotrrh^ я

>^ N О ШТГР 0 frfltra

— ртт^гіэш ^

тплуччісоеч

JSQjnil LLDO* ^ Tf »

„ЭСЛчпоУМйГ —'г

^ШСЫПІЦЕ

NAU in ï СГІ ОС L'Ai]

1ШЛp E С UX1JJN y^N

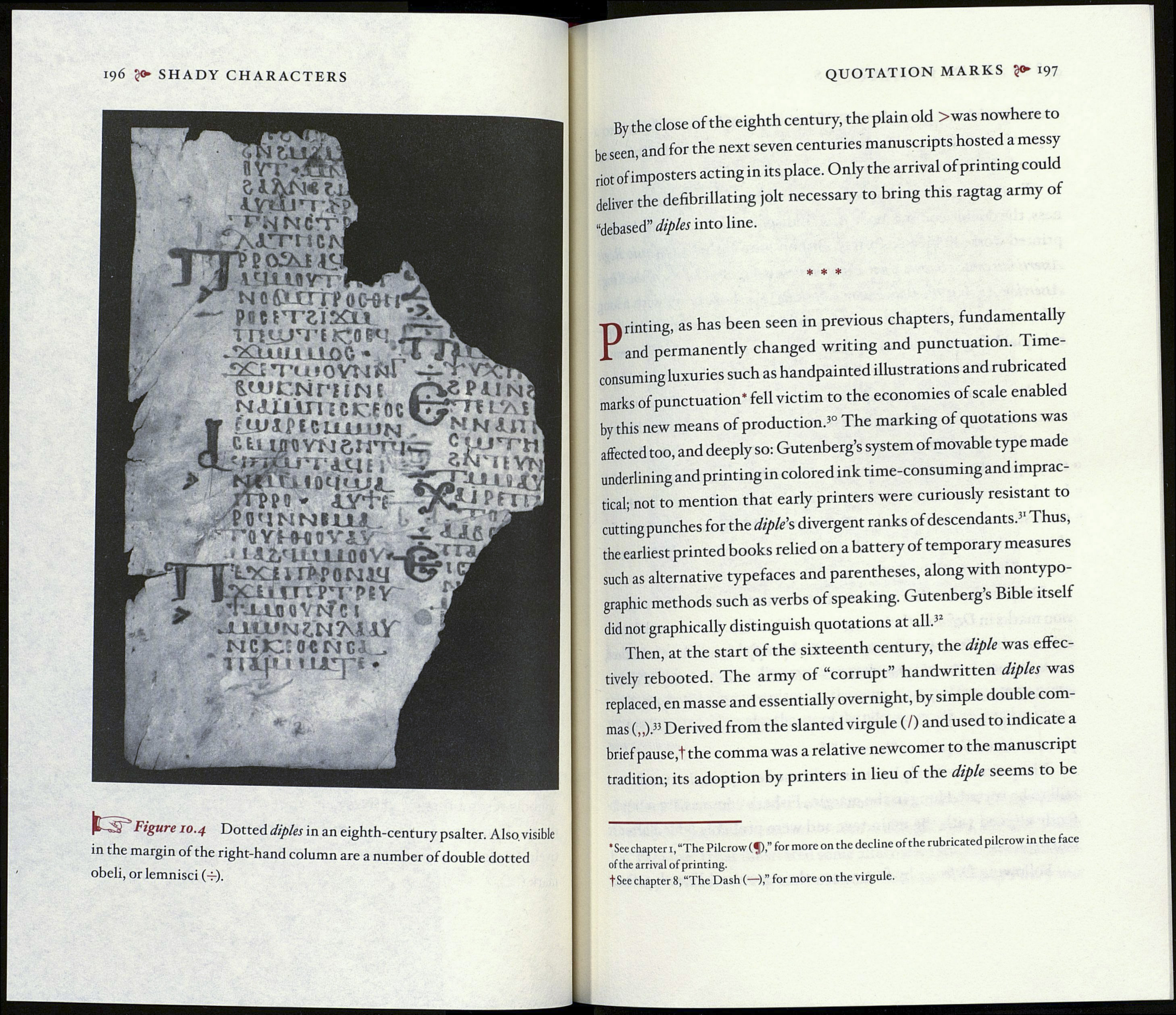

► *¿PKi№í 4 a- TS? Ѵп V xrppo - clYi-f ~д2_і P m d PO'INNIlXáL. /ГТ*Г >^ѴоѵИчіоѵау ¿.fíí r ' 1 » <12,4 M1X0 в Y«-Ä* ^ J J.7CE1 Crrrrplir ^ ’h-UJlQVtfCl Figure 10.4 Dotted diples in an eighth-century psalter. Also, visible QUOTATION MARKS ?*• 197 By the close of the eighth century, the plain old >was nowhere to -printing, as has been seen in previous chapters, fundamentally Then, at the start of the sixteenth century, the diple was effec¬ • See chapter 1, “The Pilcrow (*),” for more on the decline of the rubricated pilcrow in the face t See chapter 8, “The Dash (—),” for more on the virgule.

иг^«x^ 1 ГРТ O M іы r*^11

меіс:оегт

11Ц11 » UTp •

in the margin of the right-hand column are a number of double dotted

obeli, or lemnisci (H-).

be seen and for the next seven centuries manuscripts hosted a messy

riot of imposters acting in its place. Only the arrival of printing could

deliver the defibrillating jolt necessary to bring this ragtag army of

“debased” diples into line.

X and permanently changed writing and punctuation. Time-

consuming luxuries such as handpainted illustrations and rubricated

marks of punctuation* fell victim to the economies of scale enabled

by this new means of production.’0 The marking of quotations was

affected too, and deeply so: Gutenberg’s system of movable type made

underlining and printing in colored ink time-consuming and imprac¬

tical; not to mention that early printers were curiously resistant to

cuttingpunches for the diple’s divergent ranks of descendants.” Thus,

the earliest printed books relied on a battery of temporary measures

such as alternative typefaces and parentheses, along with nontypo-

graphic methods such as verbs of speaking. Gutenberg’s Bible itself

did not graphically distinguish quotations at all.

tively rebooted. The army of “corrupt” handwritten diples was

replaced, en masse and essentially overnight, by simple double com¬

mas Derived from the slanted virgule (/) and used to indicate a

brief pause,t the comma was a relative newcomer to the manuscript

tradition; its adoption by printers in lieu of the diple seems to be

of the arrival of printing.