i88 3®> SHADY CHARACTERS

desultory pages that follow are as nothing compared with the entire

chapters she devotes to the apostrophe and comma.4 The quotation

mark is quietly competent, thank you very much, and would like to

be left alone to get on with things.

* * *

r I A he germ o{ the modern quotation mark lies in a symbol that has

-L lurked in the background throughout this book. Introduced at,

yes, the Library of Alexandria, the diple, or “double” (>) was placed

alongside a line to indicate some noteworthy text, while its dolled-up

sibling, the dipleperiestigmene (>■), or “dotted diple,” was used to mark

passages where the scholar differed with the reading of other critics'

Created by the proto-critic Aristarchus in the second century вс

along with the asterisk and obelus,* and named for the two pen strokes

used to form it, the diple's pointed shape was at odds with its usage asa

comparatively blunt instrument.6 Used to indicate anything from an

engaging turn of phrase to some notable historical incident, in some

ways Aristarchus’s angular mark was an ancient counterpart to the

mamcule, that other indicator of generic readerly interest.7 But where a

manicule often afforded insight into its creator’s thoughts-а note ona

billowing cuff, perhaps, or a few lines of text in the margin-the cryptic

dipie bore mute witness to whatever lay in the text.8 There is something

of interest here, the diple announced, but you must find it for yourself

Even handicapped by this vague remit, the diple stuck, and though

some ancient scribes overlooked it in favor of indenting or outdent-

ing notable lines as they wrote, for centuries the diple remained the

preeminent means of calling out important text.9

* See chapter 6, “The Asterisk and Dagger (*, f),” for more details on the asterisk and obelus

and their creation at the Library of Alexandria.

QUOTATION MARKS 2** 189

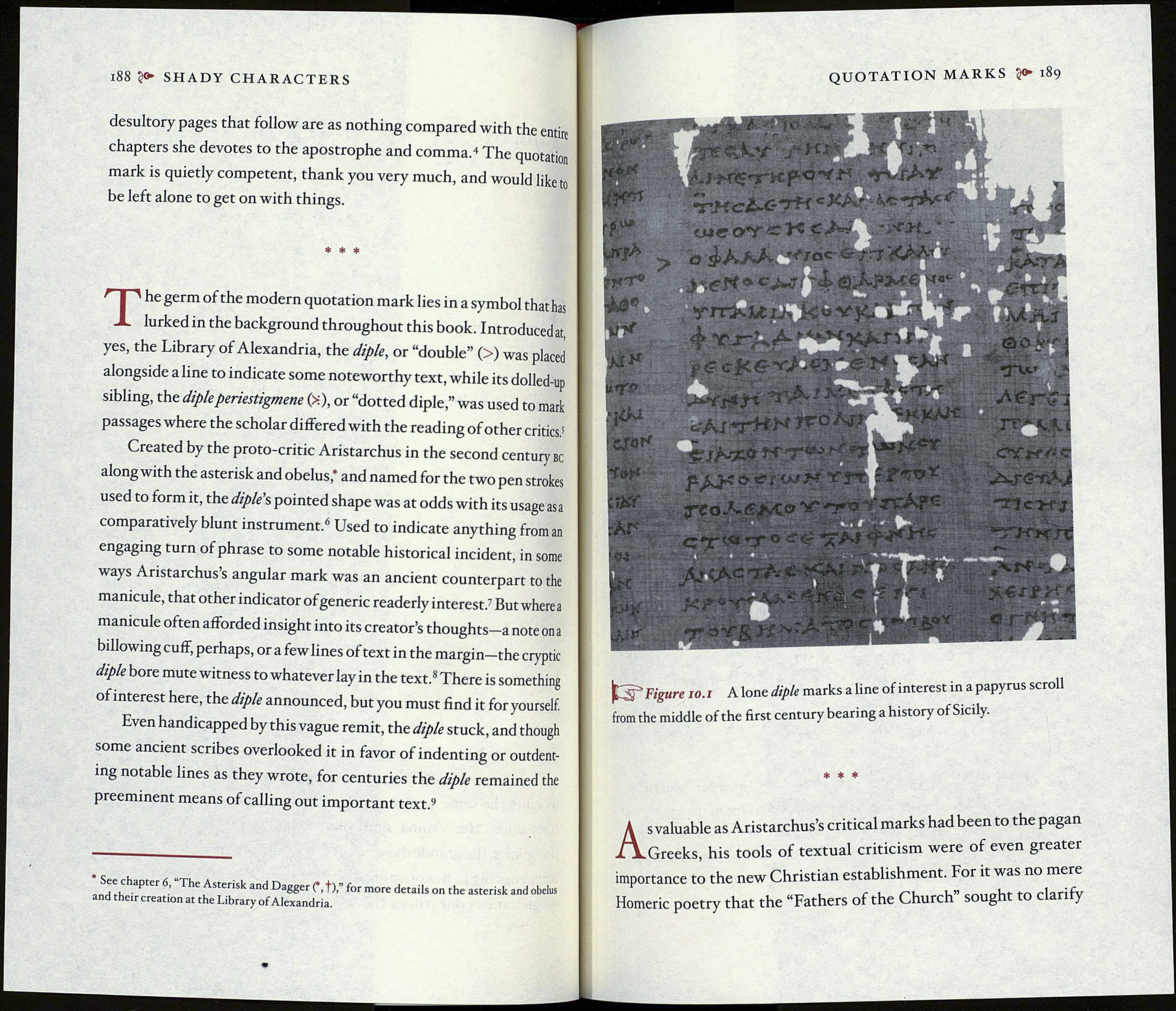

Figure 10.1 A lone diple marks a line of interest in a papyrus scroll

from the middle of the first century bearing a history of Sicily.

* * *

As valuable as Aristarchus’s critical marks had been to the pagan

Greeks, his tools of textual criticism were of even greater

importance to the new Christian establishment. For it was no mere

Homeric poetry that the “Fathers of the Church sought to clarify