and to posters and signs. An analysis of some

forms will show a decided improvement in effect by

the omission of punctuation, as in the instance of

the George A. Fuller Company advertisement on

the accompanying page. With the open space at

the bottom of the letter Y in the second line, it is

impossible to bring the comma close to the bottom

of the letter, so that it is especially prominent

and awkward. The omission of commas and periods

in other places does not materially change the

effect of this advertisement, but it is evident that

they are needless. For the same reason periods

are now omitted altogether in connection with

running head lines and folios in book work, and

very largely so in catalogue and price-list pages.

Styles in lettering. Every printer and any one

who attempts, to any extent, to design or dictate

the style of printing has immediately to do with

lettering. Book-bindings, catalogue covers, and

prospectus and announcement forms are often

made more effective by the use of specially en¬

graved lettering.

Although the present-day facilities of design and

engraving have made the use of special lettering

a conspicuous feature, the quality of lettering has

suffered thereby. There is a failure to observe the

appropriateness in the use of the different styles.

In the hurried production of the present, the

attempt is frequently to make letters which look

like some equally hurried modern example, of no

distinctive type or without following any definite

principles in the style adopted.

In Lewis F. Day’s recent book on “Lettering in

Ornament”, he says ¡“Lettering has, over and obove

its practical use, and apart from any ornamental

treatment of its forms, a decorative value of its

own, and until recent times craftsmen of all kinds

turned it habitually to account in their designs.

More than that, lettering is (or was, so long as any

care for it existed) in itself ornamental. A page

consistently set up in good type, — of one character

throughout, after the manner of days when there

was life in lettering, and not ‘displayed’ after the

distracting fashion of the modern printer, — a me¬

rely well-planned page is in its degree a thing of

beauty. To that end, of course, the letters must be

well shaped and well spaced; but, given he artist

equal to the not very tremendous task of shaping

them, or it may be of choosing them only and

putting them together, mere type is in itself some¬

thing upon which the eye can rest with satisfaction.”

The reasons for the usefulness of special lettering

are mainly two. In display lines, drawn lettering

sometimes can be made to fill and balance the

space in a better manner than is possible with

limitations in the sizes of types. Its most important

usefulness is for book covers and for printing upon

dark papers of rough textures, form and strength

of line being varied to meet the conditions as well

as to contribute by intrinsic grace and beauty.

Eccentric lettering which was prevalent in the

days of elaborately wood-engraved letter headings

and business cards, when all sorts of traceries and

shadings were made a part of the lettering, have

been perpetuated somewhat in the art department

of photo-engraving establishments. Much of the

best modern lettering is made by designers and

die-sinkers for book-stamping, as in this class the

styles have diverged the least from the fine old

Roman letter models.

The tendency to the use of wide decorative bor¬

ders and large scroll panels has proved a detraction

from lettering, and there is an increasing need for

the return and more strict adherence to the ap¬

proved models of Roman, Gothic, Old English,

and the few other styles under which all lettering

may be classed.

Instruction in lettering is given in technical and

engineering schools, in which strict adherence to

guide-lines and careful spacing are required. This

is in contrast to much of the lettering to be found

upon studies for book covers and similar exhibits

of designs by schools of art. The lettering of a

book die which must be cut deeply in metal with

precise lines is too dignified and important to be

treated in erratic design. The two styles of lettering

which harmonize best with text-pages, and in the

case of circulars and pamphlets accord best with

the accompanying types, are the plain Roman and

Gothic forms. Unless the subject matter itself is

of a distinctly literary or ecclesiastical nature,

warranting the use of an Old English or Priory

letter, any heavy or erratic lettering is in too

marked contrast to the type.

To quote again from Mr. Day: “It is no mere

fancy, then, of the book-lover or of the decorator,

that lettering is worthy of its place in ornament.

Lines of well formed lettering, whether on the page

of a book or on the panel of a wall, break its sur¬

face pleasantly. It has only to be proportioned and

set out with judgment to decorate the one or the

other, modestly, it is true, but the best of decoration

is modest; and it is not the least of the ornamental

qualities belonging to lettering that it does not

clamour for attention, but will occupy a given space

without asserting itself.”

The title lines upon book covers are in fact

inscriptions, and generally are all in capital letters.

The most excellent models are to be found upon

old tablets. Not only are letters closely spaced, but

also there is but slight distance between the words

themselves, giving a more compact and even effect

than in modern typography and lettering.

It may be said that American lettering is, as a

whole, much in advance of European work of the

present. While French vignette illustrations and

figure drawing grace pamphlet and book covers,

the lettering is frequently made by the illustrator

in amateurish script or erratic form. German

covers are in much plainer Gothic letters, but use

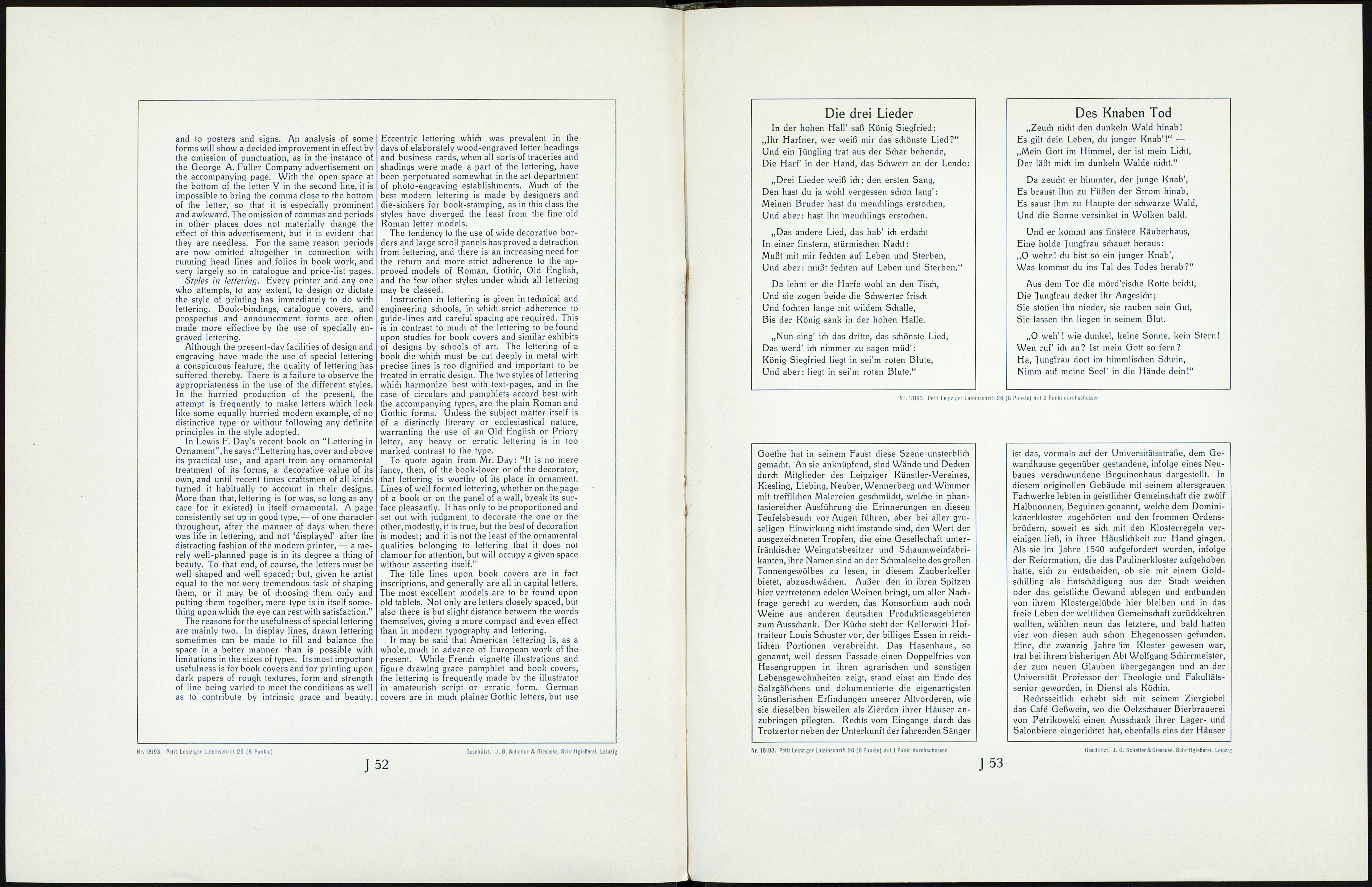

Nr. 18193. Petit Leipziger Lateinschrift 26 (8 Punkte)

Geschützt. J. G. Scheiter & Giesecke, Schriftgießerei, Leipzig

Die drei Lieder

In der hohen Hall’ saß König Siegfried:

„Ihr Harfner, wer weiß mir das schönste Lied?“

Und ein Jüngling trat aus der Schar behende,

Die Harf’ in der Hand, das Schwert an der Lende:

„Drei Lieder weiß ich; den ersten Sang,

Den hast du ja wohl vergessen schon lang’:

Meinen Bruder hast du meuchlings erstochen,

Und aber: hast ihn meuchlings erstochen.

„Das andere Lied, das hab’ ich erdacht

In einer finstern, stürmischen Nacht:

Mußt mit mir fechten auf Leben und Sterben,

Und aber: mußt fechten auf Leben und Sterben.“

Da lehnt er die Harfe wohl an den Tisch,

Und sie zogen beide die Schwerter frisch

Und fochten lange mit wildem Schalle,

Bis der König sank in der hohen Halle.

„Nun sing’ ich das dritte, das schönste Lied,

Das werd’ ich nimmer zu sagen müd’:

König Siegfried liegt in sei’m roten Blute,

Und aber: liegt in sei’m roten Blute.“

Des Knaben Tod

„Zeuch nicht den dunkeln Wald hinab!

Es gilt dein Leben, du junger Knab’l“ —

„Mein Gott im Himmel, der ist mein Licht,

Der läßt mich im dunkeln Walde nicht.“

Da zeucht er hinunter, der junge Knab’,

Es braust ihm zu Füßen der Strom hinab,

Es saust ihm zu Haupte der schwarze Wald,

Und die Sonne versinket in Wolken bald.

Und er kommt ans finstere Räuberhaus,

Eine holde Jungfrau schauet heraus:

„O wehe! du bist so ein junger Knab’,

Was kommst du ins Tal des Todes herab?“

Aus dem Tor die mörd’rische Rotte bricht,

Die Jungfrau decket ihr Angesicht;

Sie stoßen ihn nieder, sie rauben sein Gut,

Sie lassen ihn liegen in seinem Blut.

„O weh’! wie dunkel, keine Sonne, kein Stern!

Wen ruf’ ich an? Ist mein Gott so fern?

Ha, Jungfrau dort im himmlischen Schein,

Nimm auf meine Seel’ in die Hände dein!“

Nr. 18193. Petit Leipziger Lateinschrift 26 (8 Punkte) mit 2 Punkt durchschossen

Goethe hat in seinem Faust diese Szene unsterblich

gemacht. Ansie anknüpfend, sind Wände und Decken

durch Mitglieder des Leipziger Künstler-Vereines,

Kiesling, Liebing, Neuber, Wennerberg und Wimmer

mit trefflichen Malereien geschmückt, welche in phan¬

tasiereicher Ausführung die Erinnerungen an diesen

Teufelsbesuch vor Augen führen, aber bei aller gru¬

seligen Einwirkung nicht imstande sind, den Wert der

ausgezeichneten Tropfen, die eine Gesellschaft unter¬

fränkischer Weingutsbesitzer und Schaumweinfabri¬

kanten, ihre Namen sind an der Schmalseite des großen

Tonnengewölbes zu lesen, in diesem Zauberkeller

bietet, abzuschwächen. Außer den in ihren Spitzen

hier vertretenen edelen Weinen bringt, um aller Nach¬

frage gerecht zu werden, das Konsortium auch noch

Weine aus anderen deutschen Produktionsgebieten

zum Ausschank. Der Küche steht der Kellerwirt Hof¬

traiteur Louis Schuster vor, der billiges Essen in reich¬

lichen Portionen verabreicht. Das Hasenhaus, so

genannt, weil dessen Fassade einen Doppelfries von

Hasengruppen in ihren agrarischen und sonstigen

Lebensgewohnheiten zeigt, stand einst am Ende des

Salzgäßchens und dokumentierte die eigenartigsten

künstlerischen Erfindungen unserer Altvorderen, wie

sie dieselben bisweilen als Zierden ihrer Häuser an¬

zubringen pflegten. Rechts vom Eingänge durch das

Trotzertor neben der Unterkunft der fahrenden Sänger

ist das, vormals auf der Universitätsstraße, dem Ge¬

wandhause gegenüber gestandene, infolge eines Neu¬

baues verschwundene Beguinenhaus dargestellt. In

diesem originellen Gebäude mit seinem altersgrauen

Fachwerke lebten in geistlicher Gemeinschaft die zwölf

Halbnonnen, Beguinen genannt, welche dem Domini¬

kanerkloster zugehörten und den frommen Ordens¬

brüdern, soweit es sich mit den Klosterregeln ver¬

einigen ließ, in ihrer Häuslichkeit zur Hand gingen.

Als sie im Jahre 1540 aufgefordeit wurden, infolge

der Reformation, die das Paulinerkloster aufgehoben

hatte, sich zu entscheiden, ob sie mit einem Gold¬

schilling als Entschädigung aus der Stadt weichen

oder das geistliche Gewand ablegen und entbunden

von ihrem Klostergelübde hier bleiben und in das

freie Leben der weltlichen Gemeinschaft zurückkehren

wollten, wählten neun das letztere, und bald hatten

vier von diesen auch schon Ehegenossen gefunden.

Eine, die zwanzig Jahre 'im Kloster gewesen war,

trat bei ihrem bisherigen Abt Wolfgang Schirrmeister,

der zum neuen Glauben übergegangen und an der

Universität Professor der Theologie und Fakultäts¬

senior geworden, in Dienst als Köchin.

Rechtsseitlich erhebt sich mit seinem Ziergiebel

das Café Geßwein, wo die Oelzschauer Bierbrauerei

von Petrikowski einen Ausschank ihrer Lager- und

Salonbiere eingerichtet hat, ebenfalls eins der Häuser

Nr. 18193. Petit Leipziger Lateinschrift 26 (8 Punkte) mit 1 Punkt durchschossen

Geschützt. J. G. Scheiter & Giesecke, Schriftgießerei, Leipzig

J 53

к