160

BERNARD J. MUIR

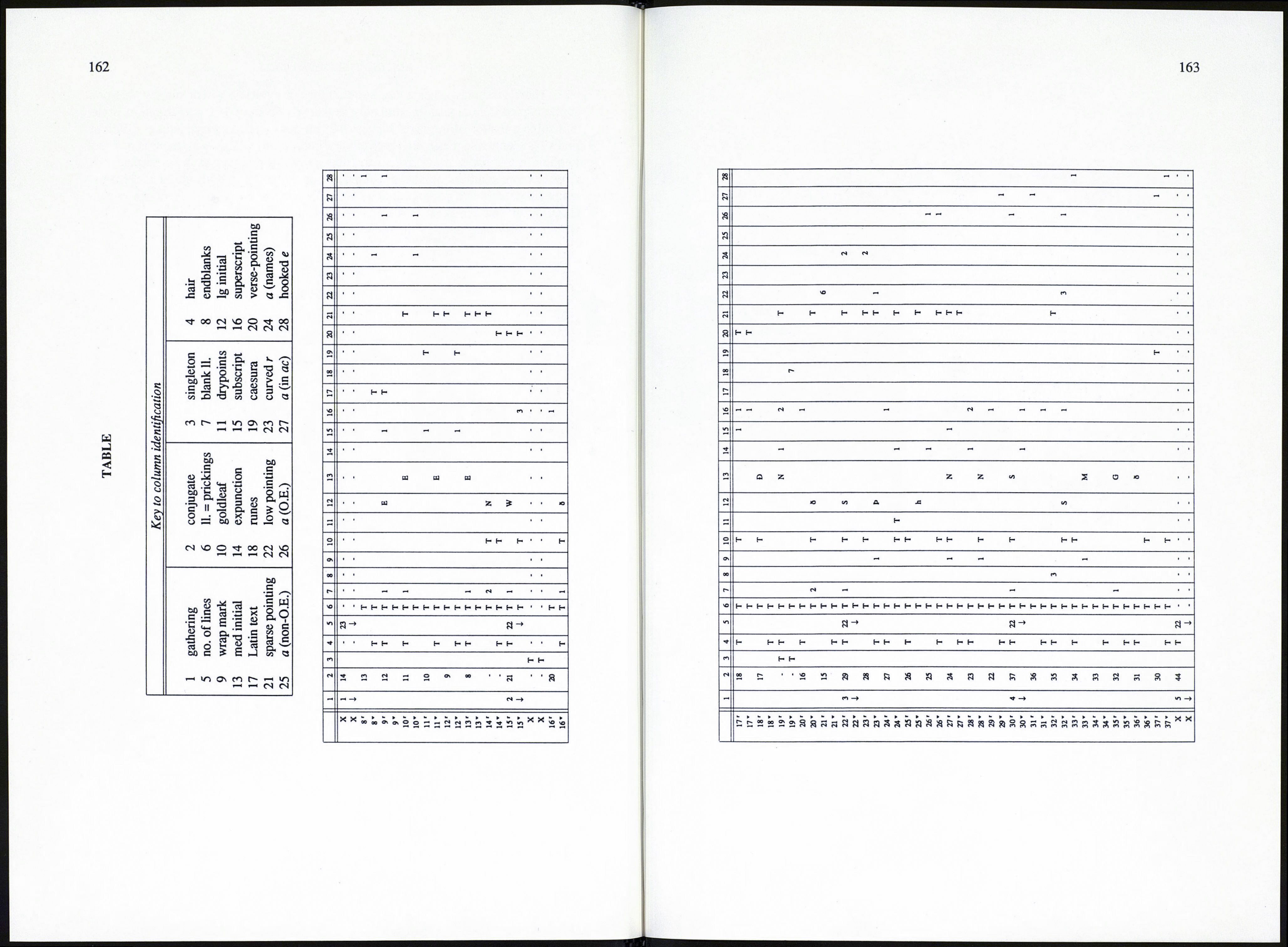

[never in Conner’s first booklet]. The oc form of the letter a is used 79 times in the

manuscript: the general impression given in reading the manuscript is that the scribe

reserved the oc form of a for special occasions, since he often uses it in proper

names (x37, Column 24—numeric) and Latin words (xl3, Column 25—numeric),

but he uses it quite frequently in less significant Old English words (x29, Columns

26-27—numeric), especially ac when it begins a new sentence or clause (xll,

Column 27). The hooked e is used on 15 occasions (Column 28—numeric), and is

not confined to any one section of the manuscript.22

Summary

Most of the observations made in this conclusion are relevant—in one way or

another—to a consideration of Conner’s ‘booklet’ theory. As Conner observes, dif¬

ferent grades of parchment occur throughout the manuscript, but I am less willing

than he to derive any conclusion from this fact. Both thick, heavy parchment and a

much thinner, fine grade parchment are found, usually mixed together in gatherings

(although the whole eleventh gathering is comprised of limp vellum). Conner

argues that three different grades of limp vellum have been used, each confined to a

single booklet (p. 234). This is a very fine distinction to make, and I should be hesi¬

tant to make much of it if other data suggest that one scribe can be seen working in a

consistent manner throughout the whole codex. It is perhaps worth noting that

defective parchment has been used in nearly every gathering,23 which suggests to

me that a large quantity of high grade parchment was not set aside for the copying of

the manuscript because it was to contain texts that were in the vernacular, not Latin,

and because it was not a liturgical book; that is, it is the sort of compilation in which

an assortment of parchments might be expected to be found.

It has also been shown that the scribe demonstrates consistent work habits

thoughout the codex—in punctuating it, in his use of large and medium size initials,

in his technique of correcting the text,24 and in his use of special letter forms (among

other things). He demonstrates by his observation of the caesura that he understands

the principles of Anglo-Saxon verse, and is most likely a native speaker (which

makes it unlikely that he would have had trouble executing large initial eths). He

has copied the Exeter Book with much greater care and concern than he exhibited in

copying the two Latin codices attributed to him, Bodley 319 and Lambeth Palace

149.25

22 On several occasions after the text was copied out, the scribe (or a corrector) has altered an œ to

an e by scraping away parts of the letter; these and other linguistic matters will have to wait to be dealt

with comprehensively in the full edition.

23 Folios 13, 28, 31, 40, 43, 44, 56, 66, 78, 80, 106, 110, 112, 113, 114, 116 and 127 had defects be¬

fore they were used.

24 As a matter of both codicological and literary interest, it is noteworthy that the scribe generally

has a lower error rate in shorter poems: this could be either because it is easier to maintain attention

during the copying of a shorter poem, or because some of the shorter poems were popular, and perhaps

familiar to him (for example, The Wanderer and The Gifts of Men are almost error free).

25 Kenneth Sisam first brought the relationship between Lambeth 149 and the Exeter Book to

Flower’s attention (“The Script of the Exeter Book,” in the 1933 facsimile, p. 85), and Neil Ker was

EDITING THE EXETER BOOK 161

There are many other, more minute types of evidence which suggest that one

scribe copied the manuscript, probably as a single codex.26 If the distribution, style

and subject matter of the texts suggest that groups of poems originated at different

times (as Conner suggests, in a preliminary fashion on pp. 240-42), there is nothing

implicit in this paper which argues that the scribe did not have as his exemplar two,

three or more smaller booklets of poems. I find, however, that my study of the codi¬

cological data to date does not induce me to support the theory that the codex known

today as the Exeter Book is a composite manuscript consisting of three booklets

written at different times by the same scribe.

the first to establish the connection with Bodley 319 (in his review of the facsimile edition, Medium

Ævum 2 (1933): 230-31). I intend to present a detailed analysis of the relationship between these

manuscripts in a separate study in the near future.

26 These will all have a place in the new edition. They include, for example, observations about

how he uses blank spaces to demarcate one text from another and how he squeezes in parts of words at

the bottom of folios (which he does in nine instances throughout the manuscript).