118 JOANNAUGHTON

church, into the presence of the hicratically frontal Virgin. Centrally placed, she

presents the Child upon her lap as though on an altar, directly before the high altar of

the church. Her monumental form clad in rich blue holds one’s attention, and it

requires conscious effort to move back to the separate plane where the patron is

seated. Despite the relatively large size of the latter and her proximity to the viewer,

she is effectively relegated to an unimportant border position outside the viewer’s

focus. Nor does the second portrayal of the patron, kneeling in profile and far to the

side of the frontal Virgin and Child within the compelling trompe-l’œil, vie for

attention.29

It appears, then, that fifteenth-century illuminators made use of a number of

artistic devices to ensure that the portrayal of a patron before a devotional image

would not interfere with the potential efficacy of that image as an aid to contempla¬

tion. The devotional group itself is invariably fairly frontal. It dominates attention

and provides an interactive experience, promoting an appropriate state of mind for

recitation of the prayer which follows. Viewer interest is maintained by the activi¬

ties of the group, especially those of the Christ Child. Although these always refer

to salvation, they are frequently unexpected, involving an apparently genre-like play¬

ful randomness. What might be seen as obligatory for the devotional group—to

show some acknowledgement of the portrayed patron and to be fully available to the

viewer—is fulfilled by the image’s near frontality. This allows for involvement in

two directions at once. There is a minimal interaction, usually involving only one

member of the devotional group, with the patron who may be placed to the side or

back; this has a negligible effect on the availability of the devotional image to the

viewer directly before it. The patron’s presence is also rendered unobtrusive in other

ways. The portrait may be physically distant on another page or part of the page, or

it may be reduced in size and placed in an obscure comer of the composition. The

intrusion of the portrait could also be moderated by manipulating colour and degrees

of compositional clarity, or by locating the portrait within a different focal range

from the devotional group.

In conclusion, it is apposite to compare a portrait of an owner not in the pres¬

ence of the depicted result of contemplation, but before a material devotional object.

A miniature by the Master of Mary of Burgundy in a collection of religious treatises

shows Margaret of York praying before a small panel.30 Here the patron, and her

retinue, are allowed free movement throughout the picture space; they are large in

size and command the viewer’s attention and curiosity, overwhelming and thus

reducing to a mere accessory the small panel before which they pray. This represen¬

tation virtually amounts to a secular portrait of a devout patron. It points up by con¬

trast the artists’ formal attempts to minimise the possibly intrusive effects of the por¬

trait in the devotional compositions examined in this study.

29 The use of the contrasting frontal and profile forms is discussed in M. Schapiro, Words and Pic¬

tures: On the Literal and the Symbolic in the Illustration of a Text (The Hague and Paris: 1973) 37-49.

The frontal figure in Schapiro’s analysis indicates a direct T-you’ relationship with the viewer, whereas

the profile involves an indirect ‘he’ or ‘she’ experience.

-3® O. Pacht, The Master of Mary of Burgundy (London: 1948) Plate 2.

A MINIMALLY INTRUSIVE PRESENCE

119

!l>(ftratt Domina

tontfa mana nta

trocí jmtmrjrtcmf

ima nimmt іш*

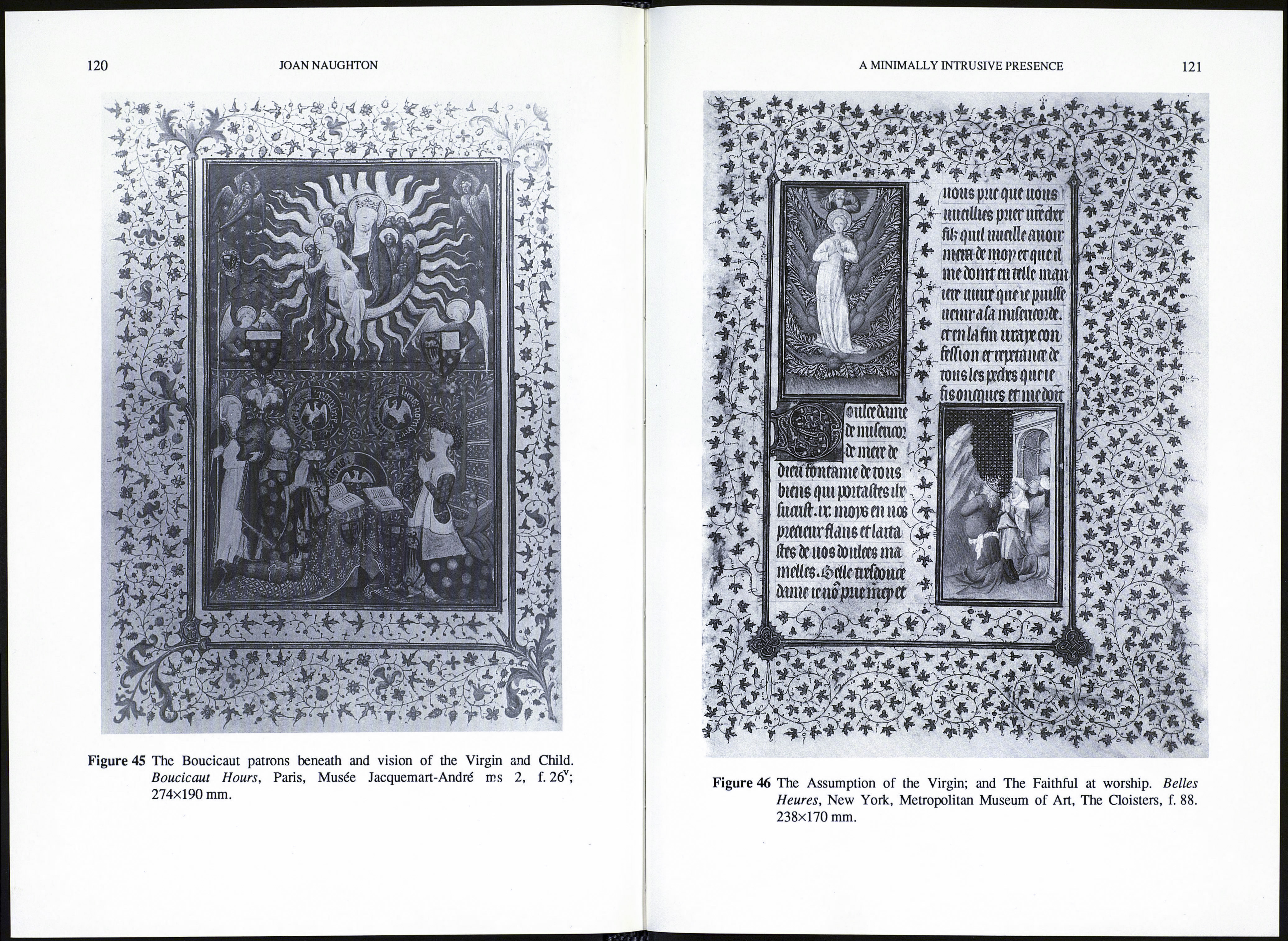

Figure 44 Amadée de Saluces and saints with the Virgin and Child. Saluces Hours.

London, British Library MS Additional 27697, f. 19; 280x190 mm.