116

JOAN NAUGHTON

Joy in the series. And it is beside this text, three leaves further on, that the Duc de

Berry is portrayed (f. 91; (Figure 47). His positioning in the lower quadrant

corresponds to that of the Faithful on folio 88. He looks upwards, just as they do, in

his case toward the textual description of the Assumption, whereas they look

towards the visual image of this Joy.22 The artistic conceit continues over the page

on folio 91v where, beside the space which her surprisingly youthful husband occu¬

pies on the previous page, is his second, younger duchess in a similar attitude of

prayer.

The presentation of a religious image on the page opposite the patron at prayer

resembles the devotional panel diptych common in fifteenth-century Flanders. The

Brussels Hours of the Duc de Berry provides an early example of this format in a

manuscript; there it serves as a frontispiece, independent of text.23 Later in the cen¬

tury, Jean Fouquet in the Hours of Etienne Chevalier links the adjacent pages by

implying a background continuum of Renaissance interior and celebrating angels.24

Potentially the viewer may choose to take a distant view and observe the whole.

However this is difficult from reading distance. Moreover there is a conceptual

difference in the environments of each group; the Virgin and Child are shown in a

close spatial relationship to the Gothic portal which acts as an isolating niche,

whereas the patron is more loosely associated with his Renaissance-style environ¬

ment. Again, the viewer is encouraged to concentrate on the devotional Virgin and

Child.

In the late fifteenth-century Hours of Joanna of Castile, the beginning of the

prayer to the Virgin is faced by a full-page Virgo lactans within a narrow frame

(Figure 48). The three-quarter slightly turned figure of the Virgin, finely featured and

with high forehead, who, in offering her breast to the Child presents its salvific

potential directly to the viewer,25 derives from Flemish panel painting near to

22 Meiss suggests that the leader of the Faithful is David, who is said to have composed the Psalms

in a chapel at the site of the Assumption in Jerusalem (M. Meiss and E.H.Beatson, Les Belles Heures

de Jean Duc de Berry (London: 1974) 255). However David in this book is invariably depicted with

dark brown hair (though it is white in the later Très Riches Heures, made by the same artists for the

same patron). The leader has grey hair, causing him to resemble more closely the depiction of Em¬

peror Augustus on folio 26 v; the dress and bodily shape of David and Augustus are identical. This

identification would fit with the observation that leaders at the time, including Berry, tended to identify

with Augustus (Harbison 91 f; M. Meiss, French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. Late Four¬

teenth Century and the Patronage of the Duke (London: 1967) 234ff.). The identification, frequently

played out in manuscripts by Berry and Augustus wearing similar dress, may here be alluded to by

their similar praying attitudes before the Assumption, the one allied to the illumination, the other to the

text it illustrates.

23 Meiss, П, Plates 179 and 180.

24 C. Sterling, The Hours of Etienne Chevalier (London: 1972) Plates 4 and 5.

25 The role of the Virgin in human salvation as intercessor before Christ is frequently spelt out in

medieval texts. Her requests rely on her motherhood. It is incumbent upon him to submit to her be¬

cause she was the source of Christ’s human flesh and provided his nourishment as a child:

“Remember, Beloved, that Thou didst receive of my substance, my visible, tangible and sensible sub¬

stance...”, to which he replies, “It is impossible for me to deny thee anything” (Miracle L in Johannes

Hérolt, called Discipulus (1435-1440), Miracles of the Virgin Mary, trans. C.C. Swinton Bland (Lon¬

don: 1928) 76). Indeed, it is this special role of the Virgin, as the most effective intercessor of all, be¬

ing nearer to God than the saints and angels, but sufficiently close to mankind so that she might hear its

pleas, which leads to the importance in medieval books of personal prayer to her.

A MINIMALLY INTRUSIVE PRESENCE

117

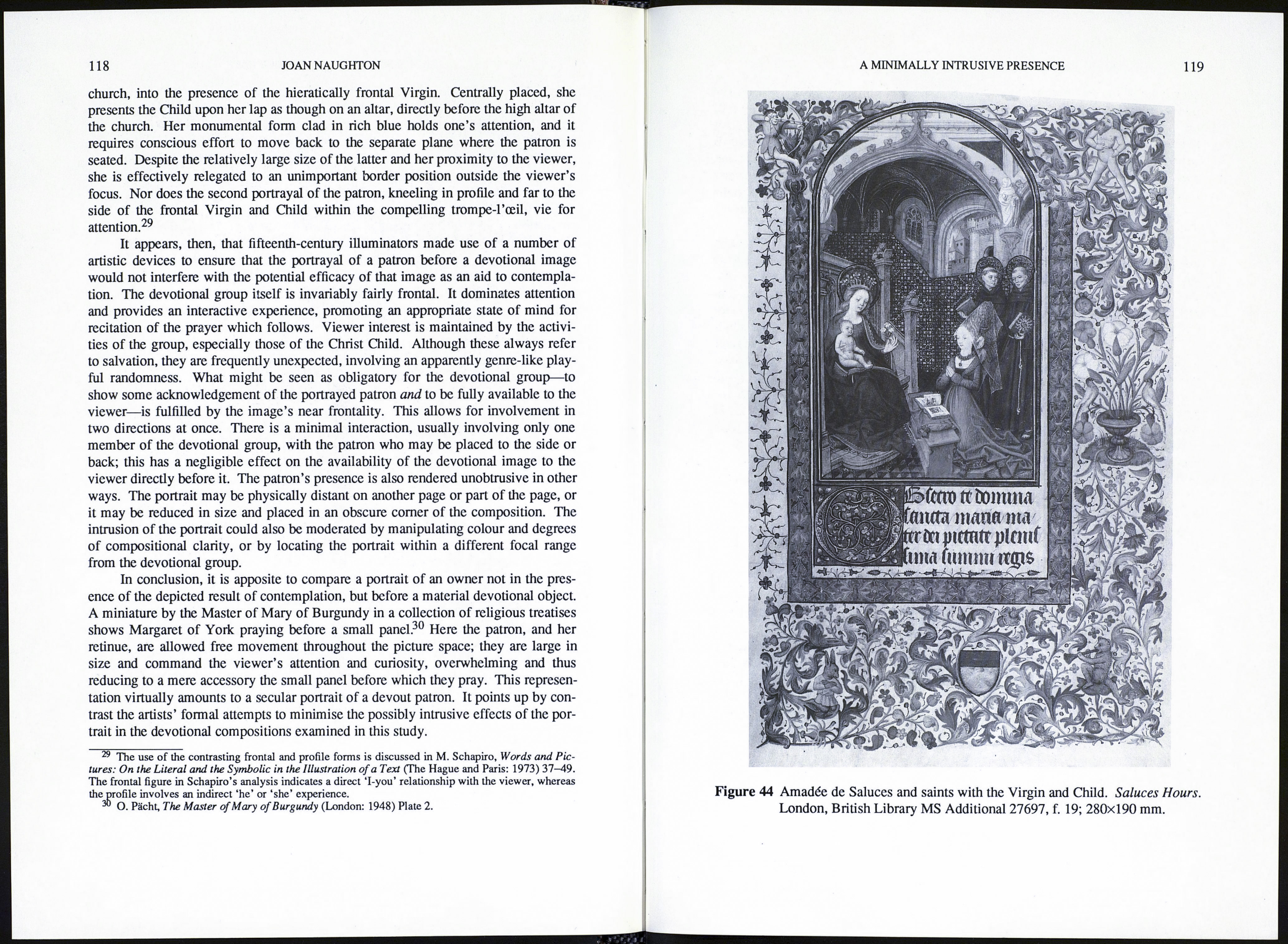

Rogier van der Weyden.26 The way this book is bound causes the large Virgin and

Child image on the verso to lie at a higher level, closer to the viewer than the patron

and St. John the Evangelist on the opposite page. Being smaller in size, and

removed further by their placement in a plane at some depth behind the page, the

patron group is subsidiary to the devotional image which pushes forward from its

frame toward the viewer. Interestingly, the patron and the Evangelist look out to the

Virgin across real space—the viewer’s space—between the leaves of the book.

The depiction of the patron as smaller in size than the sacred protagonists was

an obvious means of minimizing competition for viewer attention. This traditional

device is used in the miniature which illustrates “The Fifteen Joys of the Virgin” in

a Book of Hours from Rouen (Figure 49). Here the patron kneels close to the knee

of the Virgin who glances in her direction. At the same time, her inferior placement

and small size allows the viewer unencumbered access to the physical presence and

quiet mood of the Holy Family. The expressions, postures and gestures of the devo¬

tional group freely communicate the means of salvation through the Virgin’s role in

the Incarnation and Christ’s redemptive sacrifice.27 The Christ Child, his stiff right

arm presumptive of the Crucifixion, calls attention to his mother’s breast, while St.

Joseph and the Virgin regard him with tender sadness.

In a small Book of Hours from Rouen, the Virgin and Child occupy the picture

space immediately behind the frame of the miniature and the incipit of the prayer

which begins “Mère de dieu...” (Figure 50). The close-up rendering of Mary,

displaying her Child on the parapet behind which she stands, offers an immediate

and inescapable presence which is directed outwards. The image acts both as the

object of supplication and as exemplar, as the Virgin turns the pages of the book by

the Christ Child’s feet while he himself has a rosary around his shoulders. Almost

unnoticed is the distant, unnaturally small figure of the patron at the rear of the room

towards whom the Virgin almost imperceptibly inclines her head.

Even the competition from a portrait considerably larger than the devotional

image is to a large extent annulled by the complex play on separate focal planes used

in the full-page miniature facing the beginning of “The Seven Joys of the Virgin” in

The Hours of Mary of Burgundy (Figure 51). As Ringbom has remarked, the viewer

is placed inside, rather than outside the picture space.28 The force of the trompe-

l’œil illusion at reading distance transports one immediately into the interior of the

26 A number of panels attributed to Rogier or his workshop display aspects closely related to this

miniature, most particularly the Virgin and Child in St. Luke Drawing a Portrait of the Virgin (Boston,

Museum of Fine Arts, reproduced in Martin Davies, Rogier van der Weyden (London: 1972) Plate 76).

Noteworthy is the Virgin’s left hand, the fingers of which press above and below her breast, as are the

Christ Child’s distinctively stretched out toes and fingers, common also to the centre panel of the

Bladelin Altarpiece, Berlin-Dahlem, Staatliche Museen, and the panels of the Virgin and Child in Chi¬

cago, Art Institute and Tournai, Musée des Beaux-Arts (Davies Plates 31, 83 and 91). Equally distinc¬

tive are the features of the Virgin and the way her veil comes forward from underneath her mantle to

cross her breast and engage the mantle on the opposite side; the latter two panels also share this aspect.

27 See note 25 and the double intercession for mankind by the Virgin who beseeches Christ with ex¬

posed breast, while Christ in turn displays his wounds before God, discussed by B.C. Lane in “The

‘Symbolic Crucifixion’ in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” Oud Holland 86 (1973): 4-11.

28 Ringbom, Icon to Narrative 199.