100

VERONICA CONDON

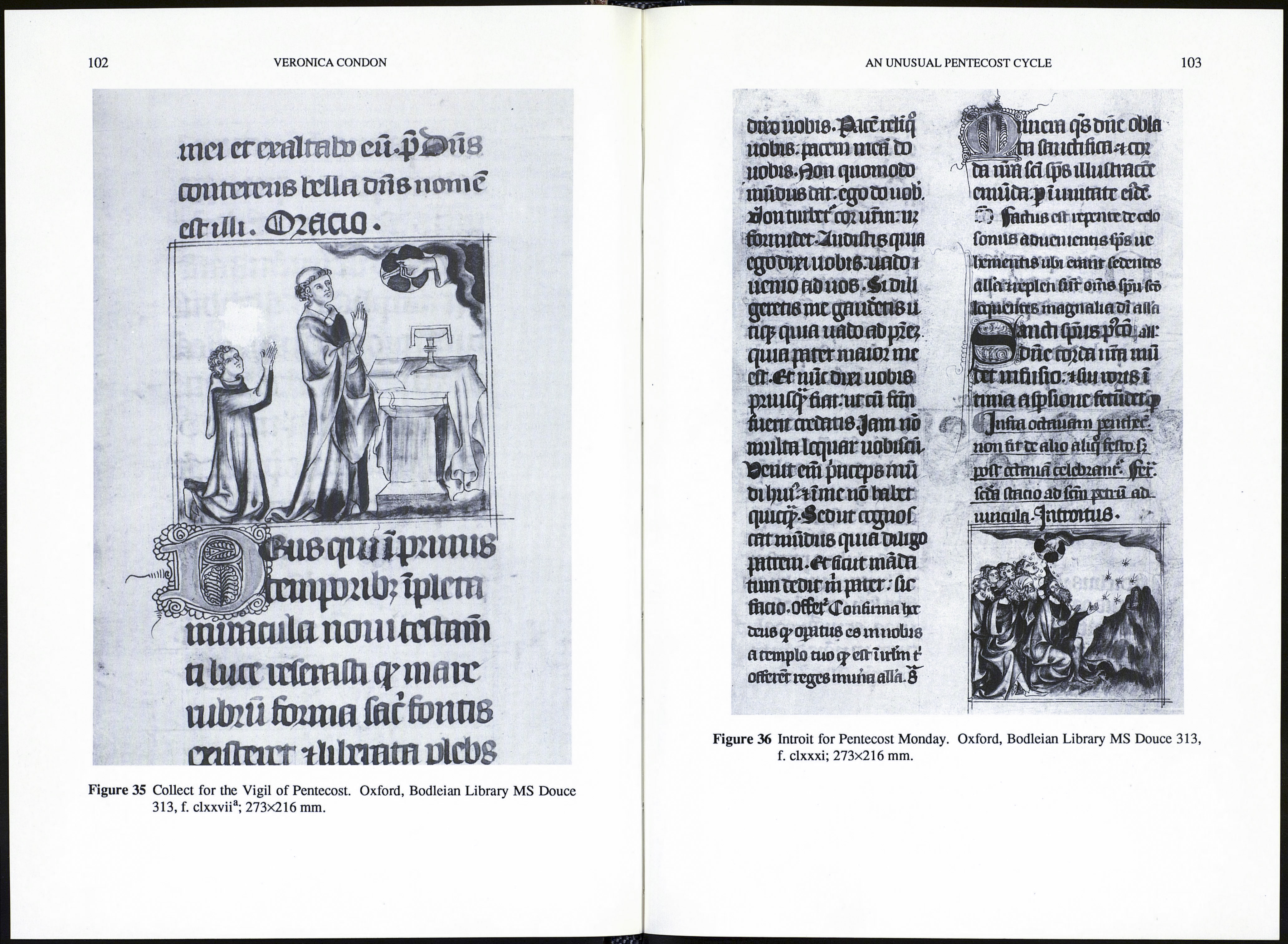

that appears frequently throughout the illustration of the Missal and also occasion¬

ally in The Bylling Bible, The Hours of Jeanne d’Êvreux, The Belleville Breviary and

the Geneva Bible Historíale. The long waisted gown of the messenger does not sug¬

gest a date of the 1360s, since similar figures are also seen occasionally in the

Pucelle manuscripts of the 1320s and 1330s. One should keep in mind the tenuous

link between MS Douce 313 and Pucelle’s atelier.23

The Gospels

Among the eight Gospels of the Pentecost Cycle there are three with miniatures

which give no indication of the text, apart from showing that Christ is speaking to

the apostles. For the Vigil and the Feast of Pentecost it would have been difficult for

the artist to convey the admonitions that begin these Gospels: “If you love me, keep

my commandments” (John 14: 15) and “If anyone love me, he will keep my word”

(John 14: 23). However, he could have introduced Nicodemus into the miniature for

Pentecost Monday, since his name occurs at its very beginning and he is often

included in illustrations of this text in other manuscripts.24

A gateway behind the apostles is the only indication that the Gospel for Pen¬

tecost Tuesday tells the Parable of the Sheepfold. The artist has either ignored or

perhaps not known the imagery traditionally used for this theme—Christ the Good

Shepherd, scenes with sheepfolds or fields of grazing sheep tended by shepherds.25

Nor has he followed any of the traditions of quite detailed illustration of the Gospel

for Pentecost Thursday, where Christ gives power and authority to the disciples and

sends them forth on their mission.26 Perhaps the artist had not realized that this was

a passage from St. Luke, for the eagle of St. John is mistakenly included in the mini¬

ature.

He went back to his usual practice of following the first words very literally

when he illustrated the text “No man can come to the Father except the Father who

has sent me draw him” (John 6: 44), words which introduce the Gospel for Pen¬

tecost Wednesday. Here Christ watches as God the Father leans down from a

heavenly cloud to gather into his arms St. John, St. Peter and a small group of the

apostles (Figure 42).27

Only two of the Gospels of this cycle show any dependence on popular tradi¬

tion. The story of the man stricken with palsy is told in the Gospel of Pentecost Fri¬

day. Here Christ is seated as the sick man is brought before him in a little two¬

wheeled cart (Figure 43). This contrasts with the usual scenes where the man’s bed

23 See Condon, MS Douce 313... Chap. IX, 51-57, “MS Douce 313 and the problems of its rela¬

tionship to the atelier of Jean Pucelle”.

24 For example, in BL Add. MS 47692, the Holkham Bible Picture Book; f. 20 v, 14th century.

25 Examples are found in:

BL Add MS 17341, Gospel book of the Sainte-Chapelle; f. 97 (two scenes), 13th century.

BN ms lat. 17326, Gospel book of the Sainte-Chapelle; f. 99, 13th century.

Munich, Staatsbibl. cod. Clm. 15903, Pericope; f. 51, 14th century.

26 An example is found in Florence, Bibl. Laur. ms Plut. VII.23, Gospel Book; f. 19, 11th century.

27 Other illustrations of this text generally show Christ teaching.

AN UNUSUAL PENTECOST CYCLE

101

is either let down from the roof of a building, or he is carried in his bed to Christ, or

else he is shown carrying his bed away after he is cured.28

The Gospel of Pentecost Saturday tells of the cure of Simon Peter’s wife’s

mother.29 The images are drawn directly from the narrative—Christ leaving the

synagogue and entering the house where the mother is seated in bed. However the

artist has ignored the tradition of including St. Peter and his wife or some of the

apostles, substituting for them two of the people who have come to him to be cured

of disease. They do not belong to this part of the Gospel, but to a later passage from

it.

The artist seems to be both limited and uneven in his understanding of the

Gospels of the Pentecost Cycle. Twice he has kept to the narrative and once he has

followed the text in a literal and imaginative way, but he appears to be less con¬

cerned with the relevance of the Gospel miniatures for the text than he was with

those of the Introits and the Lessons.

These miniatures of the Pentecost Cycle reflect the way in which the artist has

approached his task of preparing miniatures for the whole of the manuscript. He is

aware of traditions, he keeps closely to the text, yet he is inconsistent in his under¬

standing of it.

Very little of the programme of MS Douce 313 is reminiscent of the relatively

small number of profusely illustrated Missals that have survived from the middle of

the Fourteenth Century.30 Comparison, for example, with the Missal of St. Denis in

the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Lyon Missal for the Use of Paris and the some¬

what later Franciscan Missal and Book of Hours in the Bibliothèque Nationale

reveals great differences in style, iconography and in the choice of texts for illustra¬

tion.31 It is also rare to find a detailed programme for Pentecost and its Octave in

Missals with a much smaller number of miniatures.

Since the artist had so many subjects to illustrate he had to turn to a number of

sources—Gospel Books, Bibles, Psalters and many others—to find scenes he could

copy or adapt. When these failed him he had to improvise, and in this he was suc¬

cessful. Just as the miniatures were intended to make it easy for the priest to find his

place in the Missal during Mass, so also they make it possible for us, some six hun¬

dred years later, to find our way quite easily amongst the Introits, Collects, Lessons,

Epistles and Gospels of a Fourteenth Century manuscript.32

28 Examples are found in: BN ms ital. 115, Pseudo-Bonaventure; fols. 88 and 88v, 14th century;

Stockholm, Mus. Nat. ms B.1713, a miniature from a Gospel Book, 13th century.

29 Other examples of illustration of this text are found in: BL Harl. MS 1526-27, Moralized Bible

П; f. 25, 13th century; BN ms gr. 54, Gospel Book; f. 114v, 13th-14th century; BN ms ital. 115,

Pseudo-Bonaventure; f. 89v, 14th century.

30 See Isa Ragusa, “The Missal of Cardinal Roselli,” Scriptorium XXX (1975): 47.

31 London, Victoria and Albert Museum MS A.M. 1346-1891, 14th century; Lyons, Bibl. de la

Ville ms 5122; 14th century; and BN ms lat. 757, 14th century.

32 I should like to thank the librarians of the following institutions for allowing me to consult

manuscripts in their collections: the Bodleian Library, the British Library, the Bibliothèque Royale,

Brussels, the Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva, the Bibliothèque Nationale, and the Pier-

pont Morgan Library. I am grateful also for having been given access to the resources of the Index of

Early Christian Art at Princeton University, and to Dr. Isa Ragusa, Dr. Adelaide Bennett and Miss Jean

Preston who have given to me so much help and encouragement.