52

ALISON R. FLETT

follow and on the figures to whom the words are addressed in much the same way as

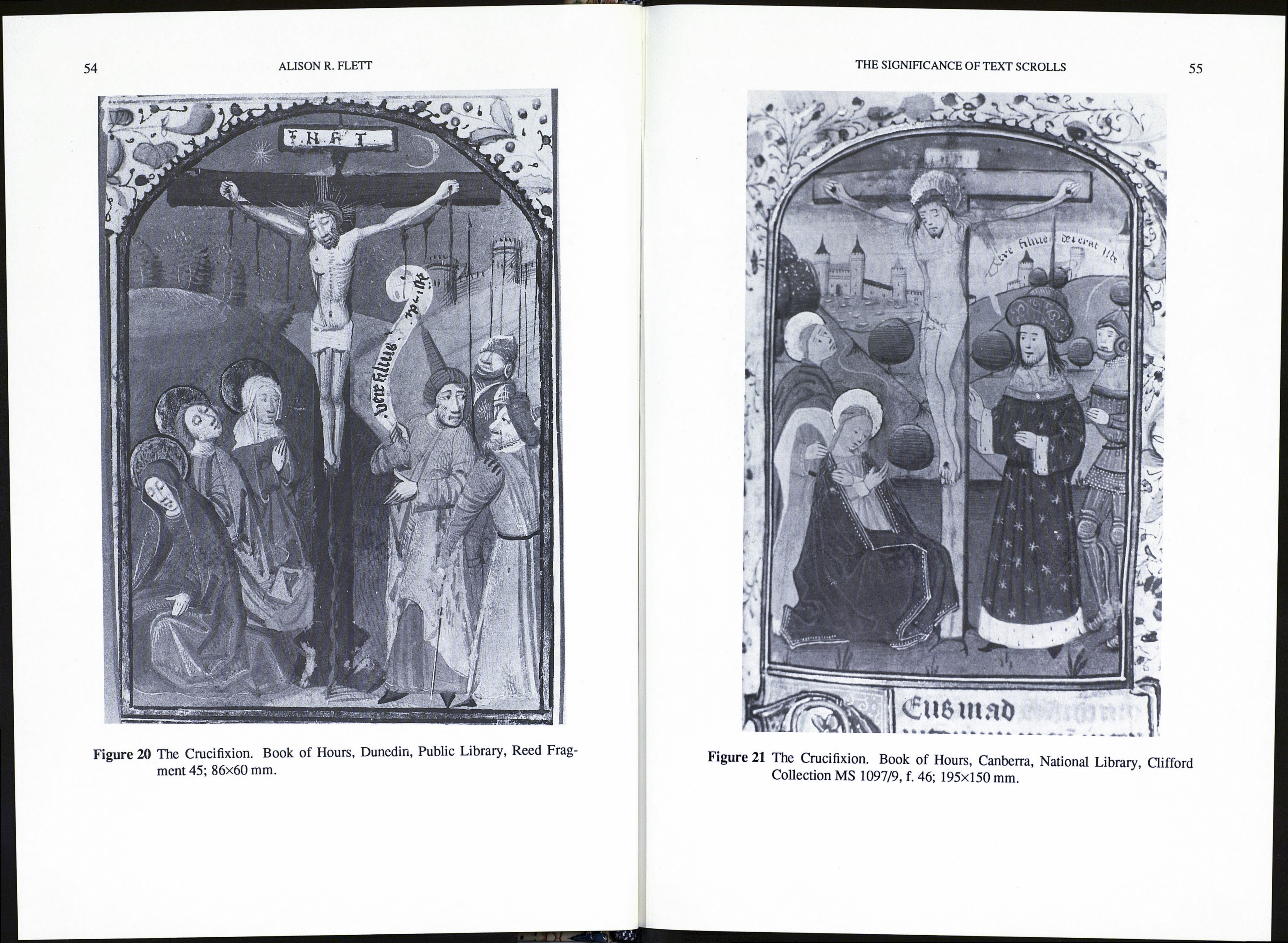

did the demonstrative “iste” in the narrative Crucifixion scene of Reed 45.

That scrolls and their texts may function in more than one way is clear when

the terms of Wallis and Sparrow are applied to the balancing scroll-texts. In the sys¬

tem developed by Wallis both scroll-texts clearly record spoken statements. At the

same time they convey information by stressing the new relationship between the

Virgin and St. John. When the composition is viewed as a depiction of a specific

moment from the Gospel narrative, and examined according to Sparrow’s

classification system, the scroll-texts obviously function as messages which vitally

affect the immediate futures of both biblical figures. The words “filius tuus” are

those placed closest to the Virgin while those nearest to St. John are “mater tua”, a

visual denotation of that cross-referral of relationships which forms the subject of

the messages. The statements could in Sparrow’s terms be classified as labels, for,

when the scene is regarded as a timeless representation of those figures and relation¬

ships identified in the scroll-texts, Mary may be viewed not only as the mother of

Christ and, by Christ’s express wish, of St. John, but of all mankind including the

user of the Book of Hours.51 That Mary is the eternal mother and St. John the eternal

son as well as Evangelist, is connoted by the miniature’s combination of figurai

images and texts. The prominent text-scrolls fix the figures in their new roles, roles

signified solely by the scroll-texts, for the figures themselves stand well apart from

each other on opposite sides of the Cross, in contrast to more strictly narrative

scenes such as that on f. 46 and Reed 45 in which St. John’s physical support of the

grief-stricken mother attests to some connection between them.

In Sparrow’s terms the scroll-texts in f. 68v are internal to the depicted

moment. They could also be regarded as having been imposed on a “fixed group¬

ing” of sacred figures in a setting which Wallis would describe as representing

rather than narrative,52 a setting in which the miniature could function as a devo¬

tional image independently of the text-scrolls. The scene’s narrative aspect would,

however, be altogether lost without the presence of the scrolls, for no other elements

in the composition indicate its narrative content. The two text-scrolls, by their phy¬

sical and verbal construction, jointly communicate the “chains of significance 53

present in this miniature which is simultaneously narrative and, as befits its prayer-

book context, devotional.

Roland Barthes contends that all images are polysemous unless tied to specific

meanings by the presence of accompanying texts which serve to focus not simply

my gaze but also my understanding”.54 However, it could be argued that images

such as the three fifteenth century Crucifixion miniatures of Reed 45 and Clifford

51 See A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture (New York: 1953) 104, concerning the wider im¬

plications of the text “Ecce mater tua”. The idea of Mary’s universal motherhood, “latently in the

mind of the Church from earliest times”, was not specifically linked to this Gospel text until the tenth

and eleventh centuries, but had been long established by the second half of the fifteenth century when

this Book of Hours was produced.

52 Wallis 8.

53 J.Maquet, The Aesthetic Experience (New Haven and London: 1986).

54 Barthes 17.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TEXT SCROLLS

53

MS 1097/9 seem rather to remain polysemous, in spite (or perhaps because) of the

incorporation of texts within the compositions.55

By their incorporation into the very fabric of the scrolls the words become

images and the verbal becomes visual. The scroll-texts in these miniatures are not

semantic enclaves”56 or examples of that jarring combination of two distinct

visual processes (seeing and reading) which both Hubert and Camille have termed

interference 57 The significance of text-scrolls as visual signs and carriers of

meaning lies as much in their impact as formal compositional elements as in the

content and arrangement of the Latin words on their surfaces. Word and image com¬

bine for maximum effect in f. 68v of Clifford MS 1097/9 and in Reed 45, while,

conversely, the form, size and placement of both scroll and text diminish the impact

of the text-scroll on f. 46 of the Canberra manuscript.

The subject matter of the miniatures lends itself to such a fusion of word and

image. As Timothy Verdón points out, the New Testament presents a more “plas¬

tic” revelation than the Old: verbal messages to prophets give way to the “total

sense experience of the Incarnation as Christ, the Word made flesh, embodies both

the verbal and the visual.58 The devotional use of Books of Hours also combined

verbal and visual as prayers were recited in conjunction with the contemplation of

the accompanying images.

Analysis of the multiple functions of scrolls and their texts in such contexts

demands a correspondingly complex and subtle discourse, with an agreed and con¬

cise terminology, especially when addressing the often multiple and overlapping

functions of text and image in text-scrolls. The descriptive terms of Wallis, Sparrow

and Peirce may well provide a useful base in the development of such a terminol¬

ogy.

55 The Reed 45 text-scroll for example retains prophetic connotations while serving as the

equivalent of a modem ‘ ‘ speech balloon ”.

56 Wallis 1.

57 R. Hubert sees this “interference” as being “almost in the acoustical sense”: “The Displace¬

ment of the Visual and the Verbal,” New Literary History 15 (1983-84): 577. The term is taken up by

Camille, Seemg and Reading...” 38.

58 T.G. Verdón, Monasticism and the Arts (New York: 1984) 1-2.