32

JUDITH PEARCE

Breviary (Figure 19). The miniature, in which the Holy Spirit has left its usual posi¬

tion between Christ and God the Father to hover at the boundary between Heaven

and Earth, is a direct illustration of the Invitatory for Pentecost from Wisdom 1:7,

“Spiritus domini replevit orbem terrarum”.25

Although the Bedford Master may have consulted with theologians concerning

the content of such miniatures, it was clearly characteristic of his mature style to

explore iconographically rich alternatives to conventional liturgical themes. The by

now conventional Dixit Dominus Trinity was to be used in another two of the half¬

page miniatures in the Temporal of the Salisbury Breviary: in the Ascension minia¬

ture (f. 26lv), where a small Trinity group watches the full-length figure of the

ascending Christ from the arched top of the miniature; and in the Advent miniature.

The Baptism, by contrast, was a new and arresting image for the Office of Trinity

Sunday. Its use avoided the duplication of themes, and at the same time, encapsu¬

lated in pictorial form important twelfth and thirteenth century doctrinal issues

preserved in the Lessons for the Office.

IV

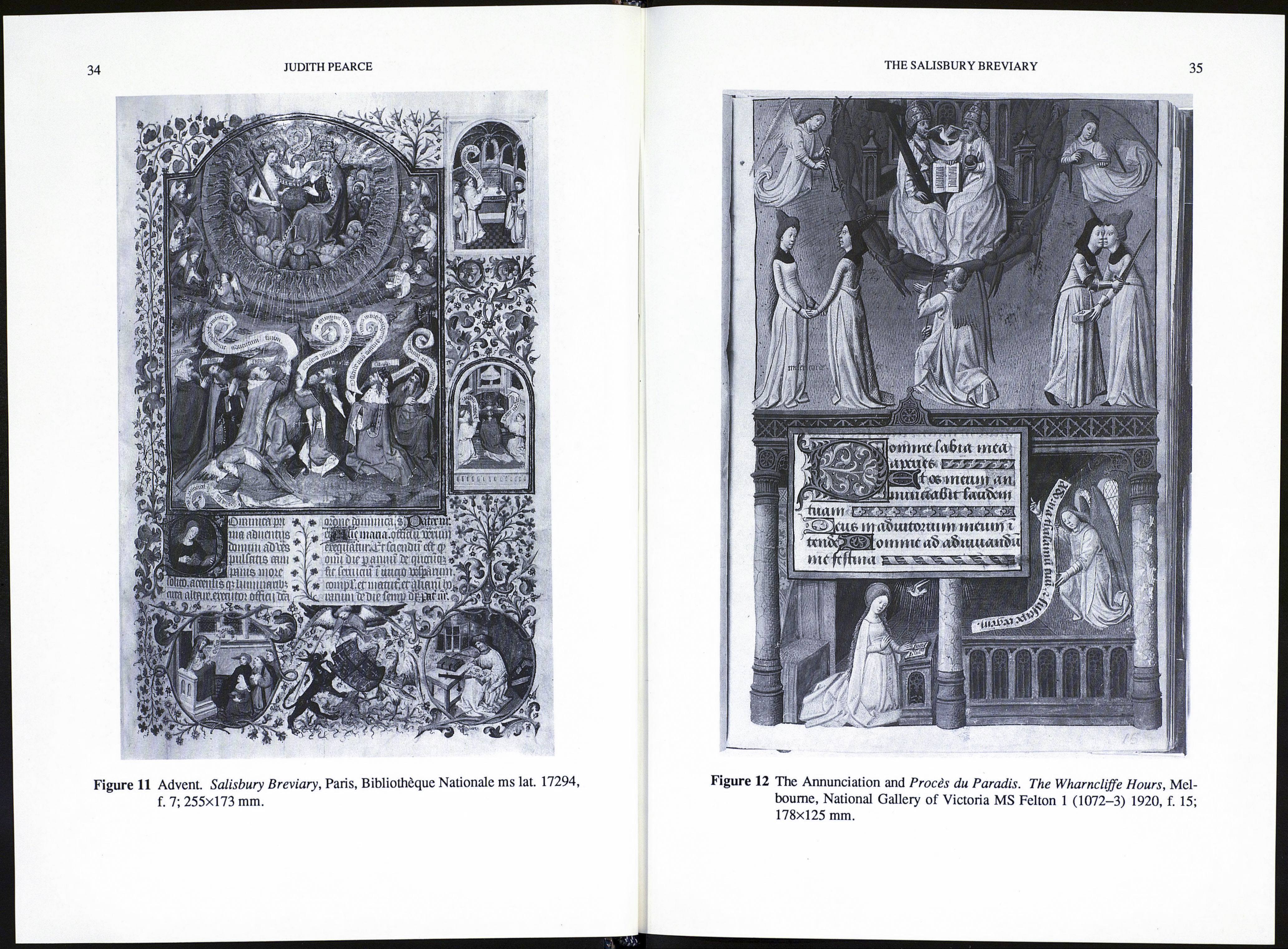

Since the large miniatures for Advent have been excised from the Orgcmont Brevi¬

ary and the Breviary of Jean sans Peur, and because no winter equivalent of the

Châteauroux Breviary has survived, there are no similarly direct analogues for the

pictorial treatment of Advent in the Salisbury Breviary. Nonetheless, it is not neces¬

sary to look outside the traditions of Parisian Breviary illumination to find precur¬

sors for each of its elements. The designer was clearly aware of the many ways in

which the Office could be interpreted in visual terms. The miniature is related to the

“Aspiciens a longe” tradition through its hieratic structure and its set of representa¬

tive Old Testament figures in fervent attitudes of prayer. The Annunciate is incor¬

porated in the initial. David is shown amongst the Old Testament figures as the

ancestor of Christ, and Isaiah as the prophet of his Incarnation. The separate figures

of Christ in Majesty and the risen Christ illustrating the first Vespers Chapter in the

Belleville Breviary are combined in an image of the Trinity, which brings together

the God of the Old Testament with the risen Christ and the Christ of judgment in a

single celestial form.

The artist’s authority to use an image of the Trinity to open and close the

Liturgical Year also lay in contemporary views of the shape of the liturgy, inherent

in the texts for the Office. It was accepted doctrine that the Old Testament revela¬

tion was a Trinitarian one. God the Father was usually the agent depicted in such

scenes because of the appropriation of this operation by the first Person of the Trin¬

ity, but the two images were interchangeable. It was similarly admissable to

25 “For the spirit of the Lord fills the world”. The English barge in the seascape is one of the rare

topical allusions in the manuscript. A simpler version of a seascape overshadowed by the Holy Spirit

may be found in one of the border medallions illustrating the Hours of the Holy Spirit in BL Egerton

MS 2019, a mid-fifteenth century manuscript painted by the Bedford workshop, with a conventional

Pentecost scene in the main miniature: Janet Backhouse, Books of Hours (London: 1985) Plate 43.

THE SALISBURY BREVIARY

33

exchange the figure of Christ for a Trinity group in the Majesty image used to illus¬

trate Trinity Sunday in the Châteauroux Breviary. The same process occurred in the

theatre. In the opening sequence of the Passion d’Arras a single actor playing God

the Father represents the Trinity according to the doctrinally sound stage direction,

Cy est la Trinité en paradis с’ est assavoir Dieu le père. The English version in the

Ludus Coventriae (or N-town) cycle, however, gives speaking roles to all Three Per¬

sons of the Trinity.

Such variations on a theme of religious experience in forms approved by the

Church all worked from within a shared orthodoxy. The connection between the

Advent miniature in the Salisbury Breviary and the two pageants mentioned by

Spencer is not coincidental, but neither is it essential to an understanding of the

miniature. It is more likely that the Advent miniature indirectly influenced the com¬

position of the miniature in the Whamcliffe Hours, than that they both shared an

early fifteenth century model illustrating the Procès du paradis. Similarly, both

pageants were types for Advent, and borrowed their position in the mystery cycle

from the Office.

One important aspect of the Advent miniature still remains unexplained by

reference to either pictorial or dramatic precursors. Only two of the scroll texts are

taken directly from the Office of Advent. “Obsecro domine” is the pre-Lauds

Responsory for the first week in Advent, and “Ostende nobis” is a Versicle, derived

from the Penitential Psalm “Miserere mei deus” (Ps. 50: 3) which was used as a

Chapter Responsory at Sext during Advent.26 The meaning of “Statim veniet”

(Mai. 3: 1) in the context of the Advent miniature is clear, but the Chapter from

Malachi was used only in the Office of the Purification of the Virgin. “Domine prcs-

tolamur” is not used in the Breviary at all. Its closest biblical parallel may be found

in Isaiah 8: 17, “Et expectabo Dominum...et praestolabor eum,” (but see also

Judges 6: 18, “Ego prestolabor adventum tuum”).

This group of texts, regardless of their exact source, gives to the Advent minia¬

ture a fourth, didactic, role. Clerics had an important part to play as intermediaries

between the laity and the Divine Office. It can be demonstrated that Bedford’s own

chaplains worked closely on the decorative programme of the Salisbury Breviary.

At least two of his agents prepared lists of subjects for the enormous border cycle.

They were not as involved in the main figurai cycle, but the use of texts from an

external source in the Advent miniature bears witness to the collaboration of a cleric

in its design. The main function of the texts is to provide the user of the manuscript

with a summary of the spiritual meaning of the Office in words as well as pictures.

The overall effect is dramatic to the modem viewer, and the possibility of a theatri¬

cal source for the programme cannot be excluded. As late as the 1420s, however,

the aim of illustrative art was still to represent the spoken or heard word, of which

“both picture and script were the conventional signata”.27

^ Also as part of the preces at Compline, and together with the Psalm during the blessing of the salt

and water on Sundays after Prime.

27 Michael Camille, “Seeing and reading: some visual implications of medieval literacy and illitera¬

cy,” Art History 8 (1985): 32.