204

KATHERINE MCDONALD

not tainted with any deviation.

The temple setting of the Purification, clearly expressed in the miniature

through the architectural frame and the altar table, is developed as the contemplative

focus of the prayer by means of repetition:

...To the Temple you carried with you to be purified him who, bom God

and man, added to you the glory of integrity, О Mother undefiled. To the

Temple you carried with you to be purified him who knowing our sins—

for to him all things are laid bare and open—daily cleanses us from our

most secret failings through repentance and confession; and, from those

of others, through the spirit of continence, he spares his servants. To the

Temple you carried with you to be purified him whose blood, on the

Cross of his passion, washing us from the original taint, daily also, on the

altar of the cross, through the most Holy Mysteries cleanses us, repentant

and having confessed, from our personal sins.

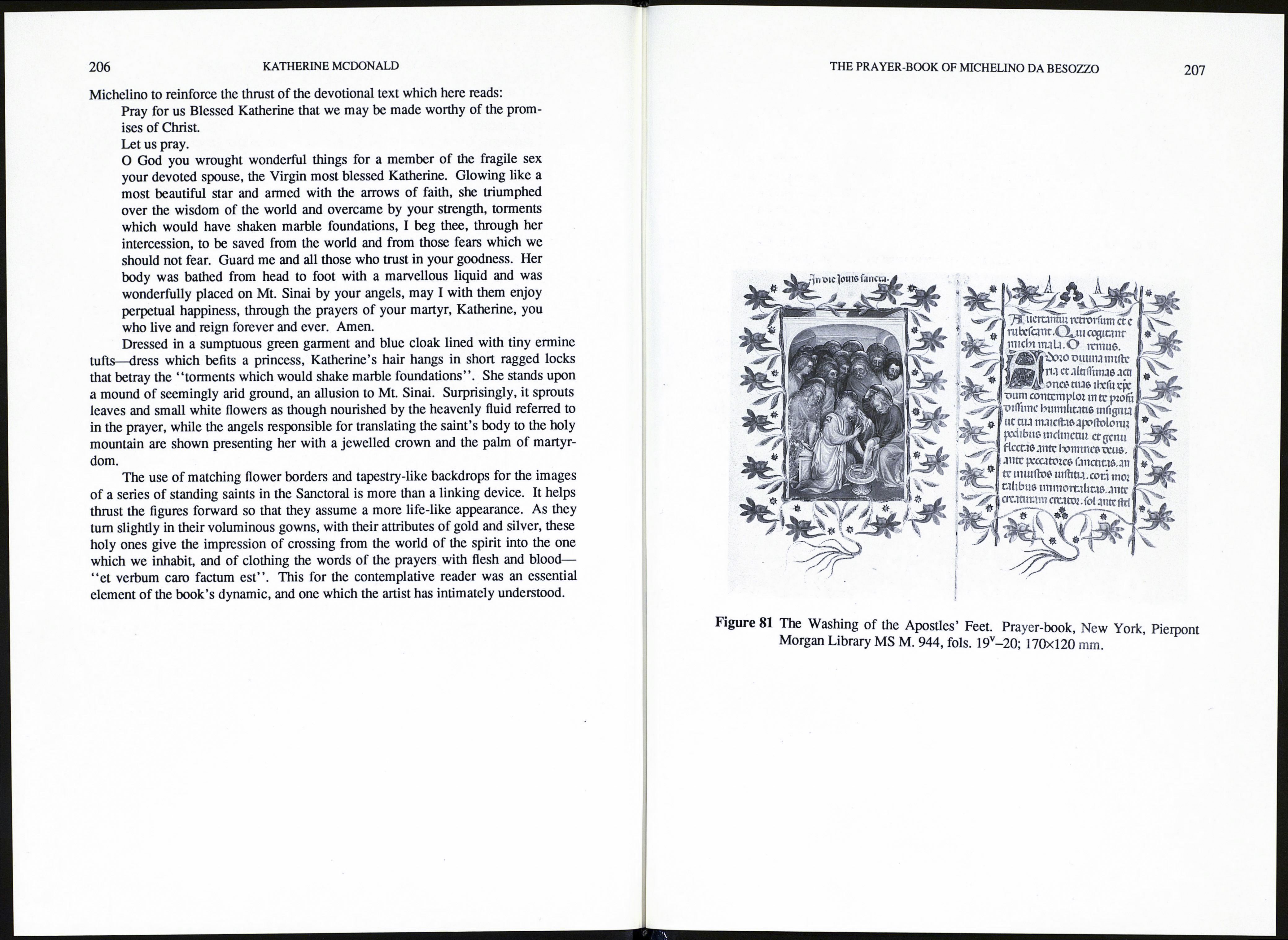

The prayer for The Washing of the Feet (fols. 20-20v; Figure 81) imagina¬

tively absorbs the reader into the solemn rite traditionally enacted within the celebra¬

tion of the Eucharist on Maundy Thursday. In developing the theme of adoration

and wonder at the Saviour’s humility, it plays on the image of the kneeling Christ,

the pivot also of Michelino’s painting:

I adore the divine mysteries and your highest actions, Jesus Christ, when

I contemplate such signal manifestation of your most profound humility,

as your great majesty bends over the feet of the apostles and God

genuflects before men...

The word “genuflects” or “kneeling” conjures up both the greatness of God

who is to be worshipped and the paradox of his performing, in the person of Christ,

such lowly service for the apostles—a paradox which is driven home in the prayer

by a series of contrasts which underline the difference between God and sinful man:

Holiness genuflects before sinners, Justice before the unjust, Creator

before the creature, Sun before the stars, Light before the darkness...

The poetry of the prayer expands beyond the immediate event of the Washing

of the Feet only to return to it with greater intensity and to the image of Christ

presented in the miniature:

...and you bend over washing, King of Kings, Lord of all Lords. There

can be no greater humility in any creature. I also contemplate you, Lamb

of God, Highest Priest and the true Pontiff who today handed over to

your disciples your flesh, a most pure Host, and your Blood to be eaten

and drunk at this noble supper...

Within such an evocative context details of the painting are also suggestive

beyond their immediate meaning. The striking vermilion red of the floor, for exam¬

ple, an unusual colour in the manuscript, aligned with the chalice-like basin of water,

visually echoes the allusion to Christ’s blood and the rite of Holy Communion.

The depiction of The Entombment and its border (fols. 24v-25; Figure 82)

takes on added poignancy as the accompaniment to a prayer which not only dwells

on Christ’s Burial but in which the suppliant also asks for a safe passage to eternity.

THE PRAYER-BOOK OF MICHELINO DA BESOZZO

205

It is as though the reader witnesses their death as well as Christ’s:

My flesh shall rest in hope. And you will not suffer corruption.

Let us pray.

Lord Jesus Christ who suffered yourself to rest in the grave so that you

might bring us out of our graves and restore us to health with the glory of

your resurrection, hear my supplications and grant that at the end of this

frail life there may be quiet sleep for me in my tomb as you ordain and

that on the day of judgement with all the saints there may be a joyful

resurrection. Bind me to yourself completely, Lord, totally possess me

so that you permit no part of me to be absent from you, but live solely in

me and make me come to live in you alone who is the true God of glory.

Amen.

The shape of Christ’s body swathed in filmy raiment is reflected in the hor¬

izontal pods of the border which, coffin-like enclose bulging peas, while the black

centres of the blue flowers vertically positioned above each border pod seem to be

lifted heavenwards in the hope of “joyful resurrection”.

Another striking example of the power of the image to bring alive the sacred

Word occurs on the opening pages for the feast of The Ascension (fols. 35v-36; Fig¬

ure 83). Michelino heightens the viewer’s awareness of the spatial zone immedi¬

ately in front of the surface of the page by projecting Christ—and one of the

trumpets—into the upper border, so that he appears to hover outside the miniature,

while his diagonal elevation is echoed by the inclined placement of the lilac border

blossoms. Their tubular forms join the trumpets in heralding the Saviour’s departure

from this earth for heaven. Exultantly, the prayer emphasises the same upward

movement of body and spirit:

God ascends with jubilation.

Alleluia.

And the Lord with voice of the trumpet.

Alleluia.

Let us pray

May my prayer ascend to you, Christ, may the prayer of my mouth, God,

enter into your sight, may my pleading reach you Lord who today as a

conqueror ascends above all the heavens and who, having conquered the

power of death, bore away the spoils of the human race, from whence

you came...

The sense of weightlessness created by the border flowers, by Christ and by the

disciples—whose feet seem to be unwillingly anchored to the ground—is further

accentuated by the burnished gold roots at the bottom of the page which, as Eisler

aptly puts it “appear to have pulled themselves from the sheltering earth permitting

the illuminated page and its prayer to rise”.10

Prayer and miniature for the feast of St. Katherine (fols. 83v-84; Figure 84)

demonstrate how the conventional iconic image of the standing saint is also used by

10 C. Eisler, The Prayer Book of Michelino da Besozzo (New York: 1981) 17.