12

THE AUTHOR EXPRESSES WILD OPINIONS.

IMeed to Know

IMPORTANT TERMS

for the DESIGNER

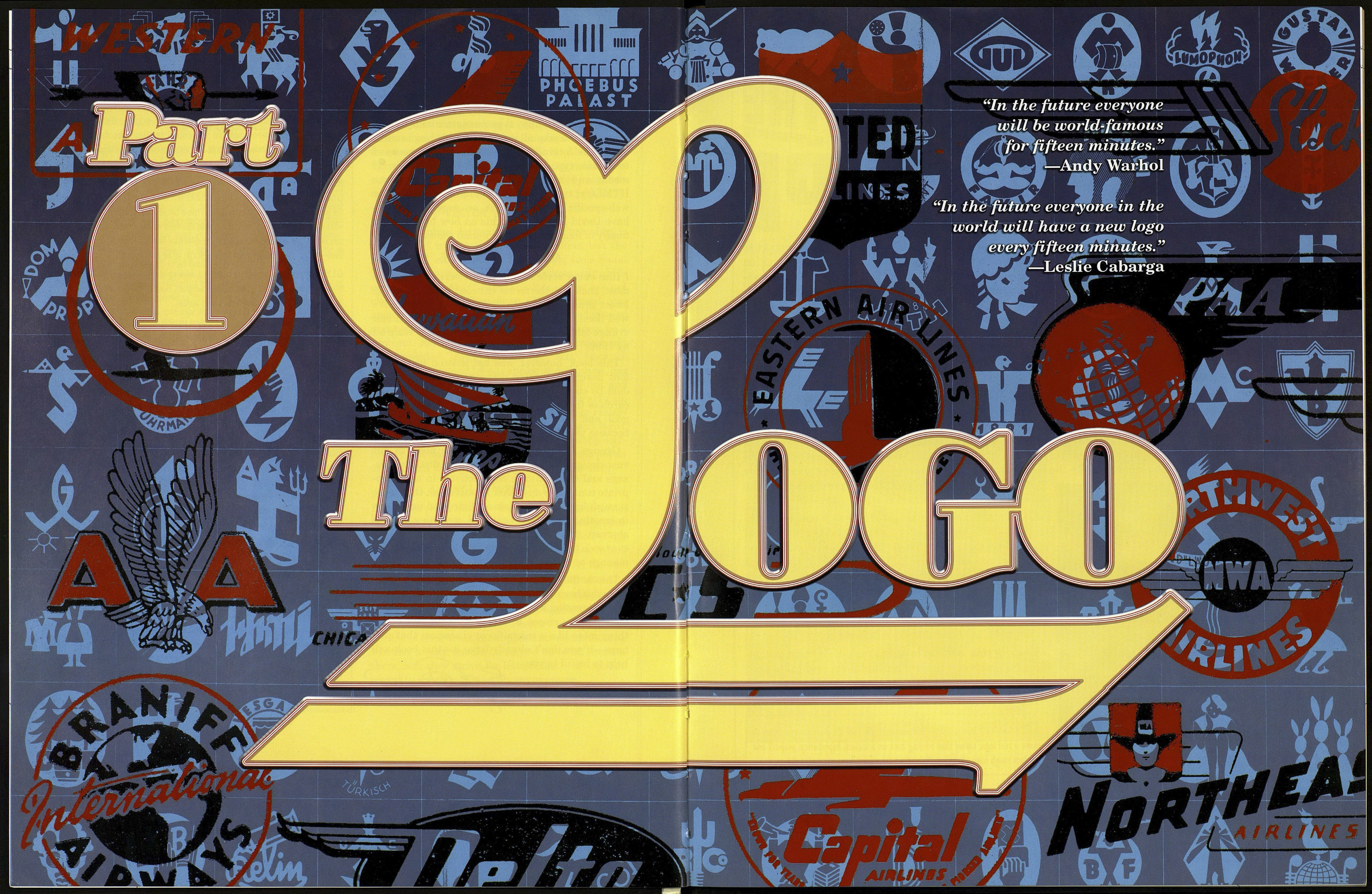

LOGO: A specific design with unique characteristics made as a corpo¬

rate "signature." A logo is pretty much the same as a trademark (TM),

although TM refers to a business device that has been legally registered.

A logo can be a nameplate or a monogram, emblem, symbol or signet. The

wealthier the corporation, it seems, the simpler the logo. A logo should

be: (1 ) Intelligible: Never confuse a potential customer. (2) Unique: Make

it different from other logos, avoid trendiness. (3) Compelling: The design

should provoke further investigation. It should "say the commonplace in

an uncommon way" (Paul Rand).

FONT: Before computers, a font was called a typeface or face. Font or

fount originally referred to the product of a foundry where hot metal is

poured into molds, and type font referred to the complete character set

in one specific point size and style of type within a type family. Now font

has become revived as the term for any computer typeface sold, traded,

pirated or offered for free.

LETTERING: Also called hand-lettering to differentiate it from

machine-made type. All lettering emerges from the hand, even when it's

a hand on a mouse. Lettering is any sequence of letters forming words

that come from the pencil, pen, brush, marker, spray can, computer and

so on, as opposed to having come from a preexisting type font. Of course,

all type started as lettering. At some point, someone drew it before it was

cast or digitized.

TYPE: Around 1982, a client called me up and said, "I need some

type." I almost said, "So call a typesetter, I'm a hand-letterer," but I'm

always polite to anyone who might potentially pay me. It turned out that

one fine day, Type became the hip term for hand-lettering. Type, as we

know, comes as the result of setting words in a font. Type is not synony¬

mous with hand-lettering.

CALLIGRAPHY: Literally means "beautiful writing." In calligraphy

we find many of the foundations of modern type, yet it has always held

the Rodney Dangerfield position in the world of lettering. Calligraphy

mainly suggests a style of flourishy, chisel-point-pen lettering, rather than

letters that are first drawn and measured, then slowly inked according to

the drawing. It really annoys hand-letterers to have their work referred to

as calligraphy. Good calligraphy has finally gained respect, though. It's

become a legitimate means by which certain ideas and emotions may be

vividly expressed in commercial lettering.

like ugly background patterns, crazy gradients, and

weird distortion tools that are mostly shunned and

ignored by professional designers. As for Fontog¬

rapher, the latest version is still six years old. At

this writing Macromedia has no plans to upgrade

for compatibility with Mac OS X. Meanwhile,

Pyrus FontLab, a new font creation program, has

come on the scene. We compare the three programs

on page 224.

VECTOR vs. BITMAP

Creating pixel lettering in Adobe Photoshop is

not covered in this book. It can be done, but the

limited and incomplete vector-drawing tools found

in Photoshop would make it unnecessarily diffi¬

cult, so why bother? Also, absolute edges are not

clearly defined in Photoshop files. Enlarged, you

always see those light/dark double pixel edges—so

accuracy in rendering lettering would always be a

problem. Everything we create in Illustrator can

be imported into Photoshop, but because

Photoshop is bound by our choice of resolution, our

logo work becomes trapped at 72 or 300 dpi and

cannot be enlarged indefinitely as vector art can,

and it cannot easily be tweaked after it is raster-

ized (made into a bitmap). I've seen company logos,

done for the web at 72 dpi, that were thereby com¬

pletely lost and unusable for print, or for the poster

or billboard that the company later envisioned.

A TANGLED WEB OF TYPE

Ten years from now, we'll realize that the Internet

of 2004 was as much a dinosaur as our early com¬

puters now seem. In ten years the resolution of our

monitors will presumably have increased substan¬

tially, and issues of creating special fonts for the web

that are more easily read will have become moot.

At the present time, however, many font designers

endeavor to design attractive, yet legible text fonts

for screen and Internet use. They try to improve the

hinting of their fonts, making minute decisions as to

whether a pixel should be turned on or off here or

there, and they strive for letterforms with optimal

legibility in a low-resolution environment.

LOGO, FONT a LETTERING BIBLE

13

I believe that, given the current limits of screen

resolution, only negligible improvements to text

type are possible. We're mostly going to be stuck

with crappy, bitmappy type no matter what we do.

I am one who sees all media roads leading eventu¬

ally to the Internet, but those designers who want

to see nice typography should instead look to print

media and not split pixels trying to fine-tune

HTMLtext type. This book, therefore, doesn't cover

web-specific fonts. However, on page 212, we do

have David Berlow's insights on how he created a

family of fonts designed for e-mail communication.

ALL STYLES WELCOME

J like every style of type and lettering—from the

most ancient letterforms chiseled in stone to the

latest graffiti sprayed on stucco—as long as it's

well done. I also like funky fonts, rave fonts, and

grunge fonts, although for me, the novelty wore off

by 1996.

This book, however, was not written for grunge

font designers—you're doing great at it already!

Just be sure, if you're making quickie grunge and

careless free web fonts, that these are really your

goal and that you're not just settling for less

because you don't know how to draw letters.

Grunge fonts certainly have their place in our

vast design spectrum. They carry a distinct mes¬

sage and communicate as effectively in an appro¬

priate context as any other font. It's just that there

is much less "craft" to making distressed fonts than

in creating by hand a beautiful, matching suite of

abstract letterforms that are unlike any others

ever seen before in the history of the world, yet still

manage to remain comprehensible.

This is the exhilaration and challenge of letter¬

ing, whether of the logo or font, that goes beyond

just impressing a few friends when they pass by it

in their cars or see it on the Internet. It's some¬

thing more like a magnificent obsession, that per¬

haps—if you don't already have it—this book will

help to instill in you. ^_^ S* 7~^

ICON: Traditionally, a sacred picture or an important and enduring

symbol. Today's ¡cons are those tiny, hard-to-see pictograms on our desk¬

tops and programs that require computer manuals to decipher. Well-

done, intuitive icons serve important navigational functions, like the

male/female icons on lavatory doors. At best they are everything a logo

should be, but even more compact.

RETRO: Short for retrospective, this became the hip term for any evo¬

cation of a period style prior to ours. I dislike this word, which entered

the parlance in 1974, my editor says, but I use it because we all agree on

what it means and it's less off-putting than the word nostalgic. And, the

user of the term isn't required to know the difference between Nouveau or

Deco—which many people don't know—it can all be just "retro."

GLYPH: This is the latest cool term for a drawing of a letter, especial¬

ly in the character slot of a font creation program. God only knows what

the cool people will be calling letters next season.

COOL: As in "cool fonts," cool is the highest possible accolade; the best

a thing can be. But cool, as in "cool on a subject," also means disinter¬

ested, aloof. Cool, actually, is a protective mask worn by the fearful. Cool

is disenfranchised, dispassionate, alienated and frightened. Cool is non¬

committal for fear that to commit to an unpopular idea might make one

uncool. Cool defined is cool dissipated. Like Dracula, cool can't know the

light lest it wither. Cool is uncreative. It follows, but does not lead. True

cool— if that term can still be used—is being true to thine own self. As

Martin Luther King Jr. said, "Our lives begin to end the day we become

silent about things that matter." Snobbery is so often a characteristic of

young graphic designers—I was a snot at twenty-five, too—it helps to

remember that no matter how fine, elegant or cool our design may be, it is

usually being used to con people into buying mundane commodities, most

of which lack quality and integrity, are unhealthful and bad for the envi¬

ronment, and in many cases, nobody really needs them, anyway.

EDGY: When clients say they want "edgy" they really mean for us to

make our work slightly obscure and a tad grungy in that safe, nonthreat-

ening edgy style that everybody else does, but not so edgy as to actually

make a statement that might upset Mr. Murdoch, Mr. Turner, Mr. Eisner

or Mr. Ashcroft. Edgy comes from cutting edge, like a design that initiates

a trend, or on the edge which refers to coffee nerves, or the state between

sanity and insanity. It indicates anger and defiance, not compliance. Edgy,

as it is used, really means to pander to the youth demographic.

Amusingly, the youth "market" never recognizes the ploy; instead it

embraces the commodity as a symbol of its own culture and generation,

even coming to define itself through mere ownership of the product.