The law of being consistent in all aspects of our lettering has already

been mentioned many times and should be enough to make the following examples

of inconsistency unnecessary. Still, it may be helpful to point out some of the more

common, yet insidious manifestations of inconsistency. Many cases of faulty lettering

are the result of resistance to reference. If we were willing to refer to a font similar

to the one we intend to draw, we might avoid committing some basic errors in letter

shapes. I call this the authorship dilemma. We are afraid to copy or use reference

because the result will be "copying," and the final job won't be "ours." Perhaps so,

but at first, we will need to copy until the correct forms of letters are more or less

permanently etched into our minds. Copying is the best teacher. Finally, there is the

problem of lack of overview and reluctance to self-criticize. I read that the illustrator

Maxfield Parrish would hang his works in progress on a wall and sit and stare at

а с

NW

DON'T let unenclosed counters, sometimes called "admitted spaces," within

letters become unbalanced. At a, the diagonal stem meets the vertical stem too nar¬

rowly at the top. At b, the base juncture is too wide, leaving unbalanced upper/lower

counters. At c, left and right slopes of Wdon't match, and the height of the diagonal

stem junctures are different. At d and e, nothing is right. See what I mean?

feahs

DON'T let your lettering become a mishmash of too many cool angles, shapes and

weird, small spaces that contribute to eye dirt. In this logo above, there is much too

much going on. Pick one or two angles, curves and shapes and leave it at that. This is

an example of lettering that's too hip for its own good.

them for long periods. I can almost guarantee you that Parrish was thinking, "OK,

what sucks about this?" Just to sit back and take the time to stare at our work—or

put it away for a while and come back to it—gains us an invaluable perspective that

can make problem areas suddenly become obvious. Lack of ego helps in this. We are

all so fragile and deathly afraid of criticism, but I feel that the ability to listen to

criticism, whether from our own intuition or the constructive criticism of another, is

the only way to become better at what we do. For example, my font Magneto

originally had a rather buxom dot over /-/' that was quite a bit larger than it now is.

David Berlow of Font Bureau, which publishes Magneto, told me the dot should be

smaller. We argued over this for days until one day I woke up and realized he was

right: The oversize dot was inconsistent with the color of the rest of the alphabet. So

I changed it.. .and the rest is typographic history. '. )

соЬѣ

DON'T mix too many neat ideas into one style. There are too many shapes hap¬

pening in the logo above, like perfect circles next to quarter circles of varying radii,

so the letters don't match as a style. And just what is going on, a, with the top of

ml Rounded corners are so easy to make on a computer, it never ceases to amaze

me how often I see bumpy transitions from curve into stem as at b, с

baseij

DON'T confuse top and bottom weights. Well, what'll it be—a top-weighted

letter style or a bottom-weighted one? Choose one and stick with it. Note also that

a thin vertical stem has been well established until the last stem of /, which

suddenly becomes wide. Also, the spine of s is too low, making counters unbalanced.

DON'T let all the spaces between shapes, which for lack of a better term I'm

calling slots, be of different widths. They should follow the same law of consistency

that demands that stem widths, counter widths, letter angle and letter spacing all

remain the same. Nothing disturbs the eye more than slots of different widths, as at

a. The logo is improved at b.Gauge balls were used to keep widths consistent.

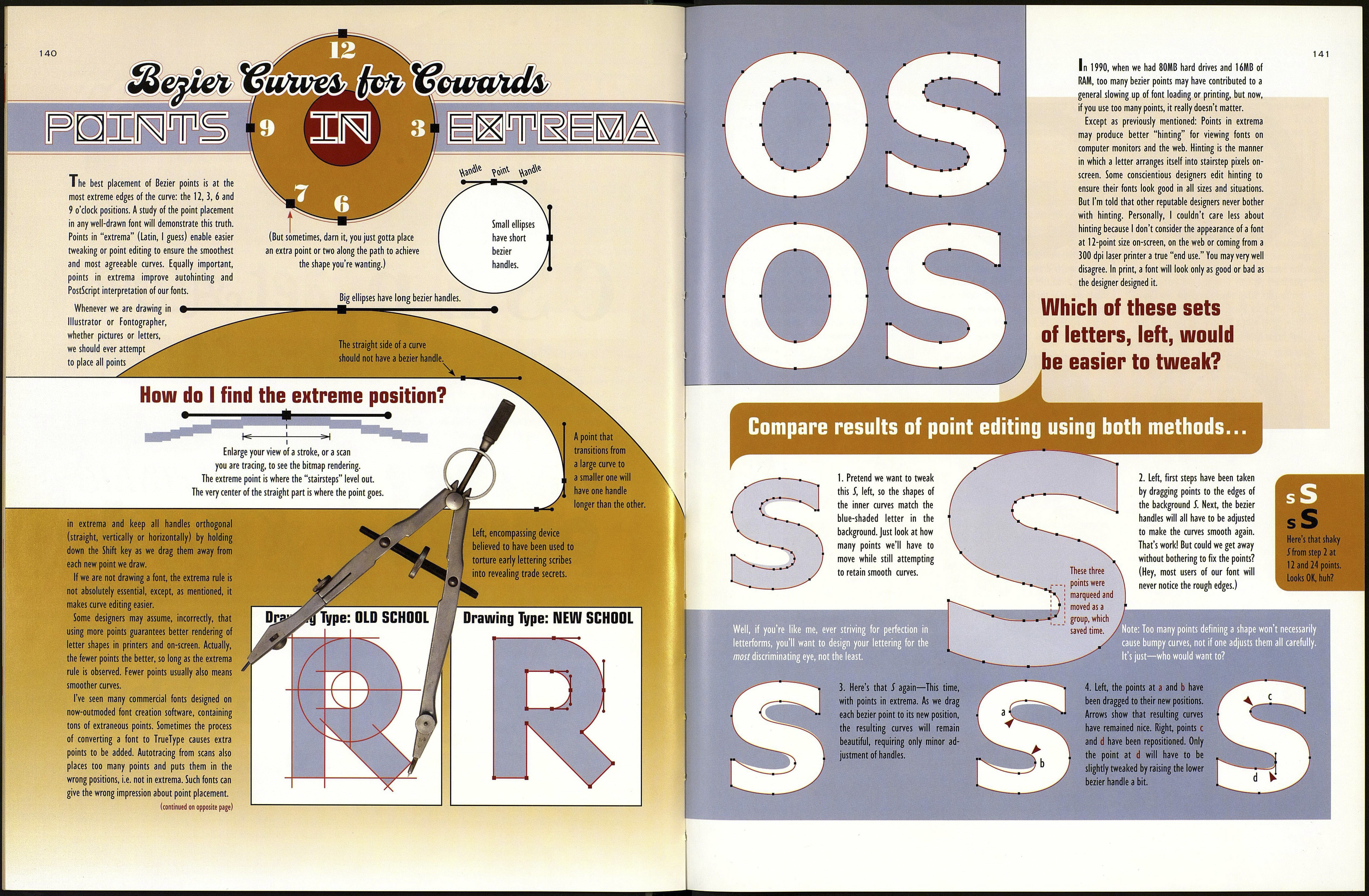

DO "draw through" when drawing letter outlines, a, so that stems passing through

other stems within the same letter will follow through accurately. Don't unite

shapes too soon. If you tweak stem widths later, you may mess up the follow

through, b. If you do need to realign stems, draw several j-curve strokes, c, from

extrema point to extrema point as guides to help you regain correct follow-through.

DON'T be inconsistent with letter shapes. At a, the letters n-u are a matched set.

They should be: и is just n rotated (although for there to be subtle differences

between them is not unusual). At b, each letter was drawn independently, without

using standard parts, so naturally they are mismatched.

DON'T let the top part of the curve, a, come around too fat. This is obviously a

contour-drawn n, rather than a pen- or brush-drawn n. Think of these curves as roller-

coaster tracks seen in perspective, b. Common sense tells us the tracks are parallel,

and as they diminish or come forward, both sides remain in parallel relationship.

C'SEpíaetcíWe

DON'T be guilty of any of the following errors: At a, the ball of the С is too small

compared with the weight of the letter. At b, the spine of letter S narrows in the

center instead of coming to its fullest width at this point, as it should. At c, none of

the serifs on this letter E are the same size. At d, the bowl of/> tilts forward though

the rest of the letter is very upright. A posthumous tip of the hat to Mortimer Leach,

who discussed these bad examples, which I've redrawn above, in his excellent book

Lettering for Advertising, 1956. (It actually upsets me to look at these letters.)

ObJECf

DO create "accommodations" whenever possible so letters may fit better together

and the incidence of spacing gaps will be lessened. At a, the original type, Kobalt

Black. At b, the sizes of all counters were increased, which decreased overall weight;

letter В was turned upside down so J could tuck; letter fwas rotated backwards so

its lower right stem could tuck under T, resulting in closing up the usual gap there.

DON'T accidentally italicize. At a, the thrust of letters a-t are clearly vertical, yet

the e seems to be slightly slanting. This can happen because e-c-o have no upright

stems to anchor them in verticality and we start to lose the objectivity to notice. It

helps to check our letters backwards by holding a printout to a mirror or just

flopping/ Reflecting letters on screen. At b, an example of a semi-script style that is

clearly upright—except for D that slants forward. I've recently observed this in

several fonts: designers don't realize that stem angles are mismatched.

ICIGIOI

DO increase the angle of slant for italicized round letters like C-G-O-Q, and also for

applicable lowercase letters which may even include the bowls of b-d-p, and so on. I

have found that the angles of rounded characters must be more acute, a, than those

with straight sides or they may appear to be falling backwards, b. The same rule

applies to diagonal-stroke letters. Notice at с that the A in this font is poorly angled.

• •

s •

I

b

DO keep the interior shapes of counters pleasing. Counters can be absolutely

symmetrical as in a, or asymmetrical as in b, c, d, yet still be nicely shaped. The

lumpy counter at e branches slowly away from the stem in a clockwise direction at

x, but on its return at y, the attachment is more abrupt. True, the counter at b is

drawn similarly, but there it's forcefully, consciously and more gracefully done.

DON'T be afraid to draw logos, fonts or lettering. Fear of trying may be the

biggest mistake of all. Sure, your first efforts may stink, but, hey, Rome wasn't burnt

in a day! Give it time, keep trying. Careful, intelligent and diligent application of all

the principles put forth in this book can absolutely compensate for any lack of

native talent. Did you know that s/he who perseveres furthers? And that confidence

and persistence will take you much farther than mere talent alone?